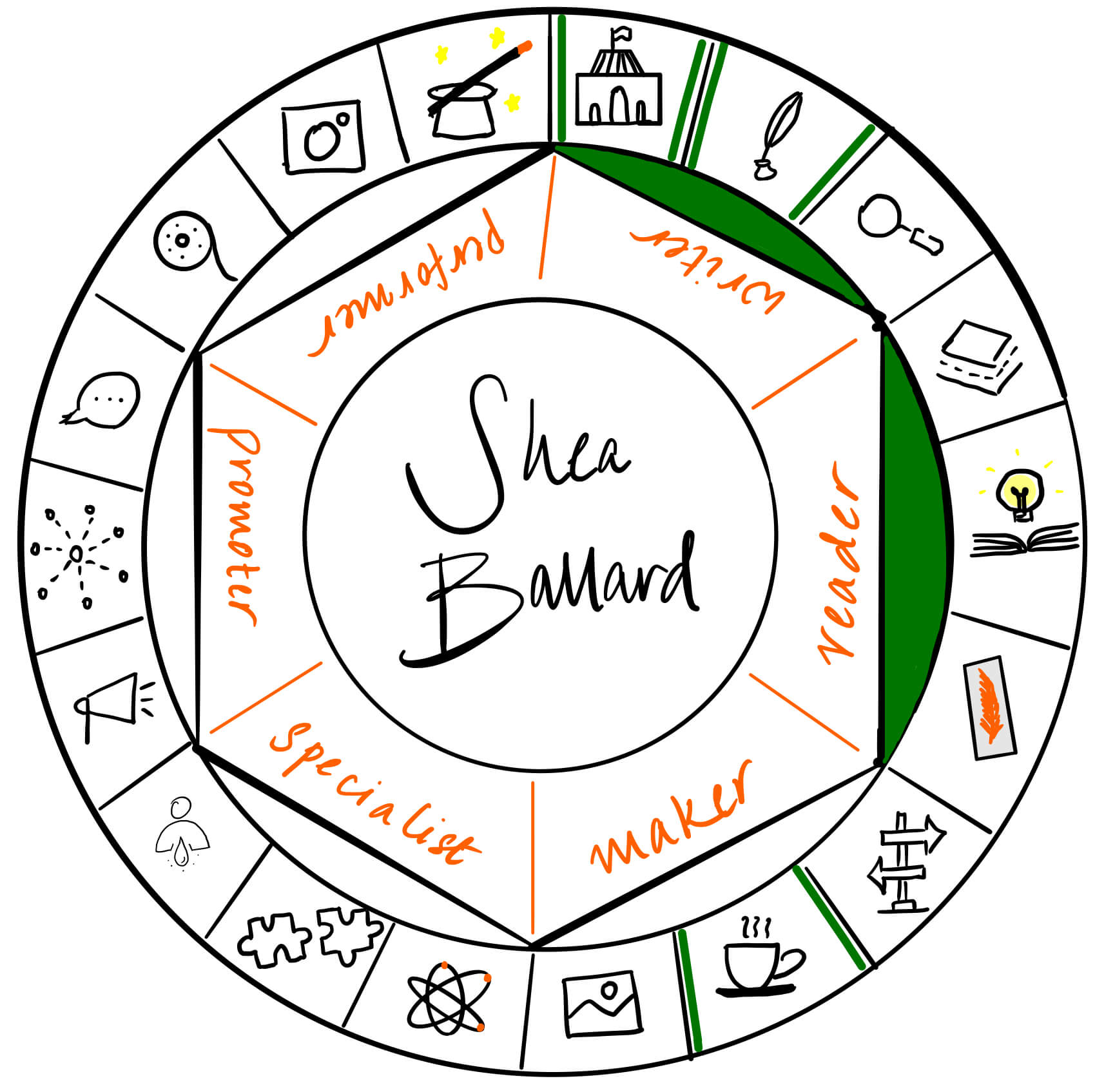

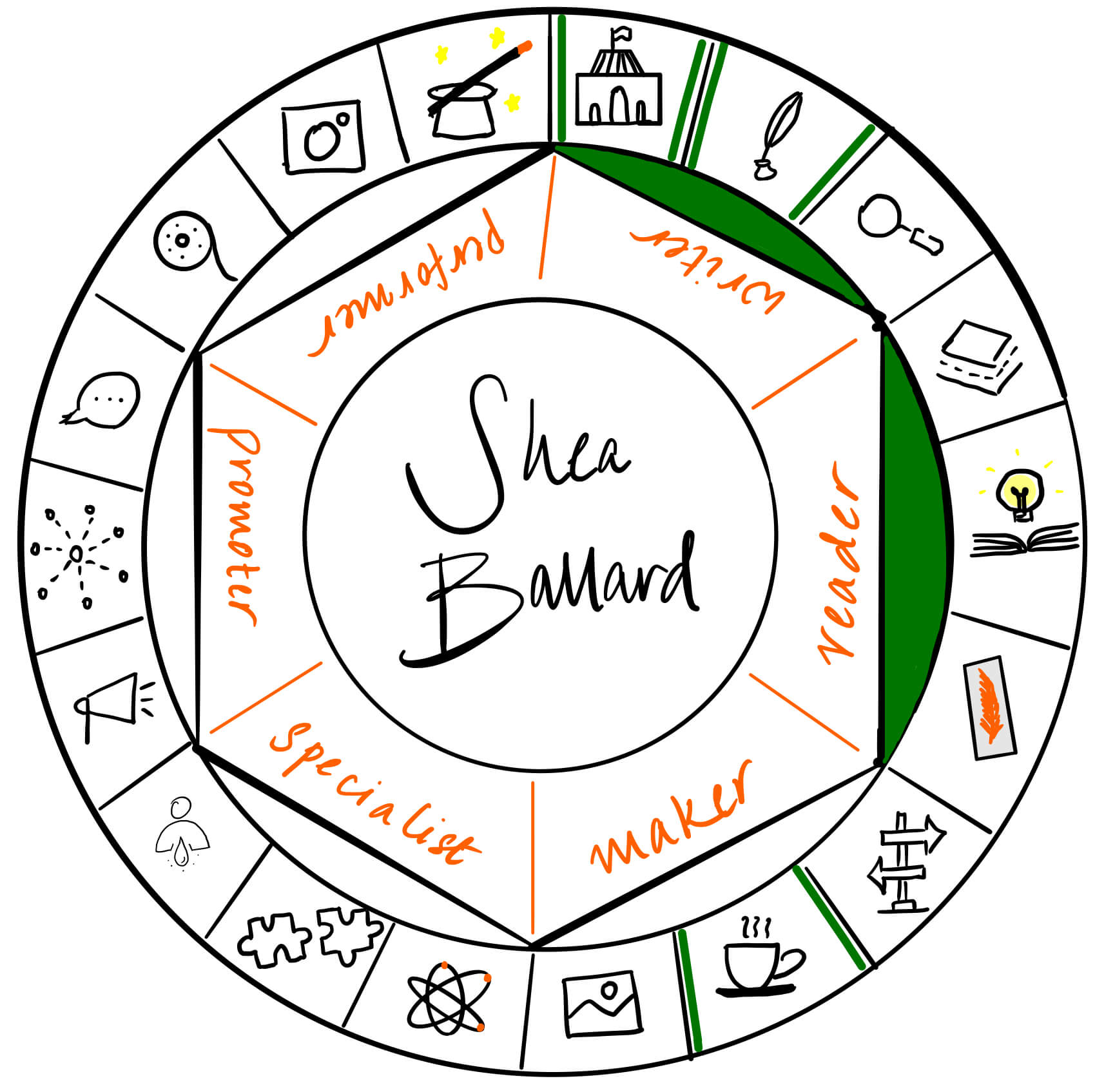

I have pondered the question of what makes an enjoyable reading experience but I have never before pondered what makes a good story. My reading experience graphic is based on the reader side of a book, but from a writer’s perspective, what makes a good story? How does one go about crafting such a story? Are there resources one can consult to learn the craft? I am thrilled to have Shea Ballard on The Creator’s Roulette today to tackle these questions.

Shea Ballard has been a reader and writer all his life. He walked into the library at eight years old and never looked back. He loves fantasy and science fiction, as well as tales of the macabre. His stories seek to take us away from our ordinary world and into places full of magic and wonder. I recently read his story in the Inked in Gray anthology, The First Stain. Let’s welcome him to the series and learn from him today!

What Makes a Good Story?

By Shea Ballard

“That was a good book.” Or movie. Or TV series. You hear it all the time. What they really mean, of course, is that was a good story. But what makes a good story? Is it entirely subjective, based solely on the reader or viewer’s psychology? Or are there objective criteria we could point to and say, “Yes, this makes a good story”? I would argue that it’s a bit of both. Everyone has their own tastes about what they enjoy in fiction. Indeed, certain genres have tropes and writing conventions expected by the audience of that genre. Generally speaking, though, is there a list of particular elements all good stories share? I say, “yes.” Here are mine. Please feel free to share your own.

Relatable Characters:

Whenever I start planning a new book (and I am a plotter), I always begin with character. Why? Because character is what makes a story a story. Sometimes young, aspiring writers will say something like, “I want to write a story about World War Two.” Well, you can’t. Not really. World War Two is far too broad a topic to write a story about. What would you focus on? And how would you tell the story? If you’re writing fiction, it’ll be told through a character or characters. That’s how we relate to stories: by sharing the experiences of a viewpoint character. A character does things, feels things, and is changed by those things. That’s really the story, not the war. The war is only the setting.

A relatable character is one who has flaws. They are not perfect. The have something important to learn, and learning that thing is the story. Ultimately, that’s what we humans care about the most. Other humans. Sure, battles and explosions are great. Who doesn’t love a good fight scene? To paraphrase Yoda, though: Wars not make stories great. Characters make stories great. Ones we can relate to because we see ourselves in them.

Completed Character Arcs:

A “character arc” describes the change a character undergoes throughout the course of a story. They start the story out in one way, and then finish it completely different. Most character arcs are the type called the “positive-change arc.” This is where the character changes in a positive way during the course of the story. Less common is the “negative-change arc,” in which the character changes in a negative way. There’s also the so-called “flat arc,” in which the protagonist doesn’t change at all. A good example of this would be Marty McFly in the first Back to the Future movie. In flat-arc stories, it is the other characters who do the changing, principally George McFly in the above example.

For a more detailed discussion on the different types of character arcs, see Creating Character Arcs by K.M. Weiland.

Conflict:

Next to characters, this is the most important part of any good story. You must have conflict. In the beginning, you introduce the reader to a character from whose eyes they will we see the story. From the start, we’ll learn the character wants something. But they don’t just get what they want because they want it. There are obstacles, people or circumstances that stand in their way. The character has to work for what they want, even suffer for it. Then there’s the character’s need, which is different from the want. Often, the character doesn’t get what they want in the end, but they do get what they need. In either case, there’s a journey to get to that want or need, and that journey involves facing some conflict. Sometimes the conflict is with a person, an antagonist. Sometimes it’s nature. Other times, they’re fighting against their self. Whoever or whatever opposes the protagonist doesn’t matter. The point is that the character must struggle against that person or thing. It is through the conflict the character faces that we end up with a story.

Show, Don’t Tell:

As writers, we’ve heard it all before; show, don’t tell. But what does that actually mean? It means to avoid too much “told prose.” Told prose is when the author is simply giving the reader information. It often reads much like a reporter talking about a news story. My editor calls it a “stop and ‘splain.” A good example of this is character or setting description. A character enters and room, and you, the author, describe what’s in the room. There are two ways to do this. One is to simply tell what the room looks like in a very told-prose kind of way. The floor was marble. The drapes were red. The chandelier was made of gold. The other, better, method is to have the character notice things and describe it in their voice.

The sound of our shoes hitting the marble floor echoed throughout the spacious room. Red drapes adorning the windows reminded me of an upscale theater, while the light reflecting off the chandelier revealed it to be made of gold. Not a gold color, but real gold. A chill in the air added to the museum-like feel of the place. Glancing at my host, I felt certain I was about to hear a “don’t touch anything.”

Now, I could probably do a bit better than that if I really thought about it, but I hope the above is a good example of “shown” description, rather than a bland explanation given by the author. The room is described by the character. They notice certain things and don’t notice other things. It is not necessary, or preferable, to give a detailed account of every new scene location, right down to the furniture. Rather, it’s better to give a general feel for the place, always in the character’s voice.

For more on this topic, please see Understanding Show, Don’t Tell (and really getting it) by Janice Hardy.

Structure:

Sorry, pantsers. I know some see this as a dirty word, but structure is actually pretty important. Most stories follow a three-act story structure: Introduction, Rising Action, and Falling Action. For more on that, see Save the Cat or Save the Cat Writes a Novel, depending on whether you’re writing a screenplay or book. Structure helps keep the right pacing and ensures that you get in all the emotional beats needed to keep readers engaged. Plotters like to figure all this out ahead of time, whereas pansters prefer to work it out at the end. Either way, the structure is necessary. Without it, stories tend to sag in the middle, getting lost in an aimless wilderness from which most readers will never emerge. Structure, on the other hand, helps to keep that journey from beginning to end interesting and exciting.

A Strong Beginning:

Nowadays, we have so many things competing for our attention. If I decide to read your book, I am necessarily deciding not to do something else. Economists call this “opportunity cost.” The opportunity to read your book costs the opportunity to have chosen another book instead. This is why I’m so big on strong beginnings. You need a hook. Something to get the reader into your story straight away.

That hook does not have to be action, though it certainly can be. The best opening hooks are rife with conflict. Yes, there’s that word again. It all comes back to conflict. Characters don’t have interesting stories without it. So why not start the story with conflict? You can begin with action, an argument, inner turmoil, a statement of theme, or even a question – which will be answered by the end of the book. However you choose to start your story, as a reader, I want it to pique my interest and invest me in your character as quickly as possible. I have bought many books simply on the strength of the opening scene. I figure if your book is this good right from the start, it must be great throughout. Therefore, I implore you to pay close attention to that opening scene, the strength of which may mean the difference between selling a book or not selling one.

Great Dialogue:

Good dialogue is an area of struggle for many beginning writers, but one so crucial to get right. The biggest mistake made is writing dialogue that is too “on-the-nose.” This means that you’re having your characters say exactly what they think and feel all the time. Most people in real life aren’t like this, and that should go for your characters, too.

We tend to talk around issues, give half-truths, and incomplete information. A lot of what is communicated in real speech is through subtext. The best examples of this are arguably from the romance genre. Until the very end of the story, would-be lovers rarely make bold declarations of their feelings for each other. They dance around the issue, hinting at it, eluding to it, but not coming right out and saying it. And honestly, it’s more interesting this way. It’s a lot more fun for the audience to be in on the protagonist’s feelings, but then watch as they struggle to get those feelings out. So, when writing dialogue, use a lot more subtext. Your character is probably not going to admit their feelings, even to themselves sometimes, until the end of the story.

Another important aspect to good dialogue is to avoid the infamous “As you know, Bob.” This is when characters tell each other things they would already know. “As you know, Bob, the villain came to power twenty years ago, and has ruled as a tyrant ever since.” People don’t talk like this. We don’t generally state the obvious. There are, however, a few workarounds.

One strategy popular in fantasy and science-fiction is to have a protagonist who is an outsider of some sort. They don’t already know all that stuff the other characters do, so they must be told. This is why Harry Potter is raised by muggles. By the time he gets to Hogwarts, he is introduced to all kinds of things that are completely new to him. “Look, Harry, the staircases move.” Now Harry knows, and so does the reader.

Another way to get around the “As you know, Bob” problem is to have characters mad at each other. In real life, people do often state the obvious when they’re angry, so you can use this aspect of human psychology in your favor.

One of my favorite examples of this, comes from a movie. In “WarGames” (1983), the opening scene shows a missile silo commander failing to launch missiles during a drill he believes is real. In the next scene, characters at NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense) are having a meeting and arguing about what happened. John McKittrick (Dabney Coleman) is pissed.

McKittrick (almost yelling): In a real nuclear exchange, we can’t afford to have those missiles lying dormant in their silos because the missile commanders refuse to turn their keys when the computer tells them to.”

Other Minor Character: You mean when the president orders them to.”

McKittrick (yelling): The president will probably follow the Computer War Plan!”

That last bit is crucial to understanding the plot of the movie. Having just seen the opening sequence, the audience now gets what the Computer War Plan is. That information, along with meeting the computer which plays the war games in the next scene, is everything the audience needs to know to follow the rest of the movie. But McKittrick would not have told that other character what both of them already knew if he wasn’t upset. It was the anger which caused him to state the obvious.

Finally, dialogue needs to be a lot more succinct than real speech. You want to avoid character rambling and excessive use of fillers, like “uhm” and “uh.” Character dialogue should be tighter and more streamlined than the way most of us actually talk. Aim for brevity, and make every word count.

You can watch WarGames here.

I could, of course, go on and on about what makes a good story, getting into such topics as avoiding excessive use of adverbs, passive versus active voice, how to handle backstory and exposition, and words and phrases (began to/started to) to get rid of in your writing, among other things. For me, though, the above examples represent the core of what makes a good story. I think if you have those seven things down, the rest of it is all going to come down to making your already-good story even better.

But what do you think? Do you agree? Disagree? Did I miss anything important? What, for you, makes a good story?

Share your answers in the comments! We would love to hear from you! To recap Shea’s points:

I hope you enjoyed this guest post by Shea! Be sure to connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.

Banner image from Visual Hunt

Be First to Comment