For everyone who loves monsters, have you ever thought about what it takes to create a monster, whether it is inspired by existing mythology or a creature purely of your imagination? Today in Creators’ Roulette, I am excited to bring you a detailed guest post by author Dorian Graves about monsters and mythical creatures.

Take a look at the six things you need to consider when working on monsters in your story. Find examples of creatures in Dorian’s novels as well as find a list of resources at the end of the post of books and works to refer to!

On Making a Monster

By Dorian Graves

So you want to make a monster.

You want to play Dr. Frankenstein, be it by birthing a beast fully-formed from your brow like Zeus with Athena, or breathing new life into a monster and unleashing it upon the world. And unlike Dr. Frankenstein, you won’t abandon your creation, but plan to let it run rampant in a story. Be it friend, foe, or fodder to your protagonists, you need to make something that stands out to your audience.

I know that feeling, tapping its claws against your breastbone, yearning to break free. And I’m here to help.

I’m Dorian Graves. Professionally, I’m an author of all things weird and queer. I also dabble in art, play a lot of games, and have a ton of biologists in my immediate family. All of this has led to a love of creatures great and small, real and fantastical alike. The weirder, the better. I write about heroes who are half-huldra, hollow on the inside with the strength of ten men, or who are bizarre aliens that grow mouths in place of scar tissue and have mind-controlling songs that help them find their soulmates. As I said, the weird stuff.

But just as every person brings a different perspective to the table, everyone has a different take on what makes a monster. And I’m here to help you find yours. Below is an outline of the steps I take when introducing a new creature to my stories. For each step, I’m going to include two examples from my own work. One will be an adaptation of a pre-existing creature from mythology, and the other will be one I formed from scratch. Whichever method you go with, I hope you have a smashing good time as you follow along.

1. CONSIDER YOUR GENRE AND AUDIENCE

That’s right; before we even begin crafting creatures, we’ve got to figure out what kind of world we’re putting it in. This is going to affect the kind of research we do, how we describe it, and so forth.

First off, genre. I don’t just mean fantasy or scifi, but the sub-genre plays an important factor. If your genre is more rooted in realism, like hard sci-fi or low fantasy, your creatures will need to stick with the rules of our world, and only deviate when you can scientifically explain how. Stronger fantasy elements let you “hand wave” away certain features. Your choice of genre will determine if your dragons breathe fire because they’re magical, or if they’ve got specialized organs and chemicals that allow them to set their breath alight. Genre can also determine how much you explain. Does your adventuring party need to know how a dragon functions in order to fight it? Or if you’re writing horror, is the creature more terrifying if we’re kept in the dark about how it functions, or is knowing the methodology part of what makes it scary?

Your audience mostly plays a factor in the way you describe the creature and any abilities it may have. Continuing to use dragons as an example, you can get away with telling a kid that dragonfire is “as hot as the surface of the sun”, while telling this to an adult will cause some skepticism (or for science-minded folks to slam your book shut) without an explanation to back it up. If you have visuals of your monster, your audience will also determine how it should look. For a video game example, go look up a Charizard from Pokemon and then a Rathalos from the Monster Hunter series. Both are flying, fire-breathing dragons with warm colors, but Charizard’s smooth design with easy-to-read shapes makes it more child-friendly compared to the rough and realistic Rathalos.

For my examples, both are going to be shades of fantasy. My original creature is from a space fantasy setting, while the repurposed creature is for the Deadly Drinks series, my urban fantasy series set (mostly) in our world.

2. WHAT’S THE PURPOSE?

Now that we’ve figured out what kind of story we’re writing, we need to figure out what our creature needs to do. Is this a throwaway beast for our protagonists to fight for one scene, or is it the crux of the entire book? Is it friendly or a foe, or maybe even doing its own thing until the protagonists show up? Are they sentient? If you have more of your story plotted out, you can dig deeper about specific requirements, like “I need a monster that seems like a mild threat, until the crew realizes it poisoned one of them in the scuffle, and then later a whole pack of these monsters is discovered and needs to be dealt with”.

For Bones and Bourbon, the first book in my urban fantasy series, I needed a recurring monster to keep my protagonists on their toes; something that could strike at any time to ramp up tension if things got slow. I also had a venomous antagonist and needed some sort of cure the characters could find in the book. Since the book plays with pre-existing monsters, I wanted to put an unexpected spin on a well-known creature…but what?

My space setting was more nebulous to start. Mainly, I needed more aliens. I had plenty that were bipedal and roughly humanoid, so I had to branch out. I also wanted something that dealt with pain; this setting is bright but violent with a smattering of body horror, with aliens that grow mouths instead of scars when injured and starships fueled with the blood of cute alien bunnies. A symbiotic alien that could utilize this somehow would fit in perfectly. Question was…what kind of creature would that be?

3. COLLECTING IDEAS

Now that you know WHAT you need, it’s time to brainstorm what kind of beastie is going to get the job done. This step is the fun part of research; it’s frolicking down rabbit holes, collecting cool pictures and articles like a squirrel hoarding away food for the winter, and entertaining any and every notion that flits through your head. Grab your notebooks and prep your pinterests, folks.

As any creator knows, ideas can come from anywhere and everywhere, but I have a couple sources I like to start when working with creatures. If I’m working with pre-existing creatures, my go-to resource is The Elemental Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures by Caitlin and John Matthews. It’s a reference of supernatural beings from cultures all over the world, and also discusses the mythical significance of various “normal” animals like cats and fish. I’ll bookmark any creature that might fit the bill of what I need, and a couple extras that sound interesting or otherwise might fit in the story.

A quick side note on using pre-existing creatures: if you’re using something from another culture, do your research as to its origins, not just their appearances in popular culture. Plenty of beings are generic enemies in tabletop and video games but are actually sacred beings in their own cultures (looking at you, rakshasas, rocs and wendigos, among so many others…). Others have said so better and more eloquently than me, but if you’re interested in using a creature from another culture, ask yourself if it’s a story you SHOULD tell. Also, make sure the creature isn’t under copyright, such as hobbits and ents.

Now, you don’t need to limit your inspiration to pre-existing supernatural beings. There’s plenty of strange life on our planet, and not just in the animal kingdom. Maybe you’ll find inspiration from a spider’s hunting technique, or in how a specific tree has grown. One of the most fascinating examples I’ve seen is the Ardulum series by J.S. Fields, whose aliens and tech are inspired by wood science and different kinds of fungi. You can also look to things like setting; what kind of creature would live in that volcano your characters are going to, or what might lurk in an asteroid belt that your starship needs to fly past?

Depending on your audience and level of realism, you might be able to simply settle on an idea or aesthetic because it’s cool and you like it. That’s a perfectly valid reason too. As long as it fits in with the setting you’ve made, go as wild as you wish.

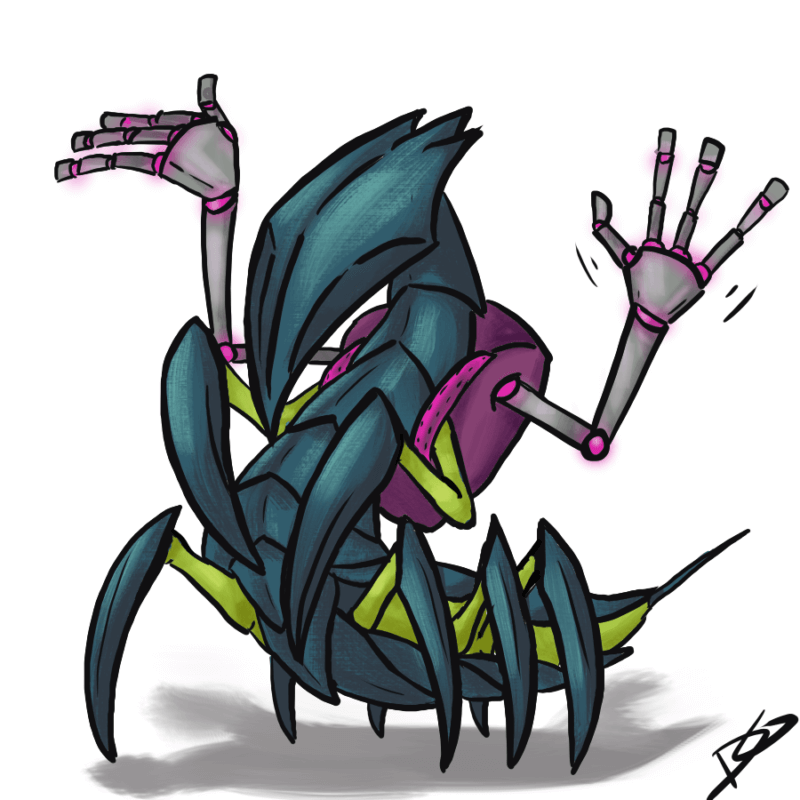

For my space setting, I somehow got attached to the idea of a creature with scythes for “hands”. I visually drew ideas from the slivers of Magic the Gathering and the chaurus from the Elder Scrolls video games (mostly in Skyrim), coming up with a chitinous insectoid with many legs and scythe hands. I gave them some camouflage, deciding that they used to sneakily attack foes, later made traps and lay in wait as they became more advanced, and now often serve as doctors or engineers on starships where they don’t have to sneak around to feed on pain. To use tools and be understood by most others, they’d likely need translators and cybernetic arms with fingers. So now we have chitin-covered bugs with scythe hands and little backpacks that have arms and translators and other devices attached, tapping away as they travel through the stars. I named them a sound they could make with their claws: the Skraks!

For Bones and Bourbon, I wanted something fast. Something that could travel in a group, so my protagonist would first encounter and fight one, then later face the whole pack he’d accidentally ticked off. I made a list of creatures, but then I found…unicorns. Unicorns have a theme of purity, and some myths have them purify water with their horns; I could also use those for purifying poisons. But why would my protagonists have to fight unicorns, especially in an action-packed urban fantasy tinged with horror (and a dash of humor)?

Cue stumbling upon a photoshopped picture of a horse with a dog mouth. A lightbulb went off in my head. What if the unicorns weren’t prey, but predators? Their horns tinged red from purifying the blood of their victims before feeding? Then to make them scarier, but also funny in a dark way: what if they didn’t die unless their horns were removed? Even decapitating one would leave a unicorn head hopping after you as it tries to gore your leg…and its battle-scarred body blindly charging nearby, forever running until it either reunites with its head or perishes. Terrifying, but also had the potential for a bit of dark humor by having a unicorn head hopping around and nipping at people’s ankles.

THE HUNT FOR INSPIRATION

Humans have a long history of making up monsters. You yourself likely did as a child, be they imaginary friends or tormentors under the bed. But how do you manage that on a creative level? Where can you turn to see how it’s done?

There are limitless resources that can be found in libraries and the internet, but here are a couple spots I like to turn to when I’m in the process of playing Dr. Frankenstein:

-Encyclopedias dedicated to creatures, such as The Elemental Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures mentioned above. There are also more specific versions dedicated to types of creatures (like Faeries, Ghosts, etc). Especially when using a pre-existing creature, flipping through a few of these can not only provide a lot of information, but will usually include citations for further research.

-Game Bestiaries and Monster Manuals. I’m a huge fan of video games and tabletop RPGs, and almost every fantasy or scifi game has some sort of bestiary to peruse. While you can ignore things like stat blocks and elemental weaknesses, look at how the creatures are described. What’s important for each setting to talk about? Do they talk about its habitat, how it reacts to predators/prey, or other interesting information? Again, consider your intended audience before deciding if you should pick up Volo’s Guide to Monsters or a Pokedex.

-Works by actual scientists. I don’t just mean textbooks and field guides (though I admit, some field guides designed to be cool for older kids by highlighting what makes creatures weird or unique can be really useful). There are also plenty of documentaries and nonfiction books designed to be engaging to casual viewers. Plus, some even get around to writing fiction! The Memoirs of Lady Trent series by Marie Brennan, the Ardulum series by J.S. Fields, and even the Outlander series by Diana Gabaldon; all of these authors are also prominent scientists who utilize their research in their work. Give them and others a read, see how the science and craft are incorporated together.

-Art books, especially concept art for games/films/etc! Not only can you find neat creature designs in them, but you often get some insights into their design process. How did Dragon Age go about differentiating demons to showcase their vices? What musicians and albums are referenced by those wild Brutal Legend designs? Or what inspired those aliens in Arrival and their unique form of language? Concept art books are how you find out, and can help with creating your own concepts.

4. BACK AND FORTH

Once you’ve got a vague idea about what you’re doing with this beastie you’ve wrangled up from your imagination, it’s time to lead them into your story. How you do this differs depending on your methodology of plotting, but there are two main methodologies I see commonly discussed when it comes to incorporating anything you have to research.

One is to get as much research out of the way as possible. Hitting the books first may uncover cool facts and concepts you never would’ve discovered on your own, so you can plan how best to utilize them once you get to writing. The one complaint I’ve noted about this approach from an author’s perspective is that if doing all the research up-front can make one feel like they have to include everything they studied in the book, either to share it’s importance to the reader, or to make up for all the time spent on the topic. Be cautious of this; there’s a reason that your audience is checking out your story instead of a textbook.

The other method is to get your ideas down in an early draft of your story, then research before the next draft. This can help determine what you’ll need to research, and also confirm that you want to use your creature the way you originally planned in the first place. Maybe you thought this would be a one-off monster, but then your heroes adopted a baby of it and now you have to figure out how it handles being a pet/familiar/etc. This method does help narrow down what you need to study, but it can come at the cost of discovering potential plot holes. Maybe the heroes have to keep a dragon from breathing fire in a gas-filled cave so they don’t all go up in smoke, but then research tells you that’s not how that particular gas and method of fire-breathing would play out; time to either rewrite some details, or spit in the face of science for sake of story.

Speaking of which, a quick note: you don’t have to follow what already exists, if it doesn’t suit your story. Forgoing some things may have a bigger impact than others. For example, I nixed the concept of unicorns being attracted to virgins; it had no place in my book, and I also didn’t want to tangle with the thorny definitions of virginity in a queer context. Again, what you can get away with disregarding for your story may depend on your audience. A hard sci-fi story won’t like you chucking the laws of physics out the window. But if it’s a minor scientific detail, or if you’re shaking up a creature’s traits to better fit your story? Go for it. This is your fiction too.

Either way, you’ll likely hop back and forth between researching and creating—you know, making the thing you actually set out to do?—for the bulk of the project. Once again, how much or how little depends on the nature of your story as discussed above. I didn’t research too much on unicorns, basing them off of myth and one particularly ornery Shire horse I knew as a kid. The Skraks get a bit more research every time I work on my space setting, mostly as I nail down what kind of real-life creatures one could mash up to make a race of sentient, pain-eating aliens clacking away in their little laboratories.

5. PART OF YOUR WORLD

Alright, you’ve got a creature (or several) in mind for your story, and you’re somewhere in the writing process. How will you make your creature feel like an integral part of the world, instead of a cool idea stapled onto the plot? And if you’ve got research left to do, where do you focus your efforts so you don’t fall down a rabbit hole and research something inane like amphibious digestive systems?

What you need to do is show how your creature leaves its mark on the world, literally. Showcase to the readers that there’s a world beyond the plot they’re reading, and create the illusion that life goes on even after they’ve closed the book. This sort of subtle worldbuilding may sound hard, but it can be as simple as leaving a footprint.

Consider when you take a walk outside, how even in the most urban areas you’ll find traces of creatures around us. Bird feathers (and droppings on buildings). A dog’s footprint accidentally immortalized in cement. Branches shuddering as an unseen creature darts through the undergrowth as you pass. Traces like these can be added for subtle impact, foreshadowing the existence of a creature and its place in the world. With my unicorns, for example, I led up to an encounter with one by having one character track its footprints, and then find the corpse of its prey; this showcased how it left a physical mark on our world. We also had a sighting of it before noticing anyone, where it used its horn to purify a puddle to drink out of (a callback to the archetypical serene image of unicorns…nevermind that the puddle was blood). Side characters also talked about the unicorns in the background of other scenes, showing that they weren’t just nuisances for our protagonists.

These are minor examples, and it’s so easy to go deeper. Consider, where does your monster lie in the food chain of its ecosystem? If there are humans or other sentient beings nearby, how do they regard it? Do they take advantage of this creature at all (harvesting from its body, or scavenging leftovers from its prey), do they try to drive it off somehow, or do they coexist in some other way? Unless a nearby society (or the creature itself) is incredibly new to the setting, they should have ways of interacting with the creatures around them.

One of the most notable examples of this I’ve seen is in the Monster Hunter series of video games, especially the recent Monster Hunter World. Not only are the hunter’s weapons and armor crafted from monsters, but the entire village is built from them. Buildings and signs are built from both wood and monster bone. Botanists collect monster droppings as fertilizer, chefs cook with the meat you bring them, and the entire society revolves around connections with the world outside their walls. (And if hunting isn’t your speed, you can always get away with peacefully subduing most monsters while gathering plants and bugs…or at least, I do.) Plus, the characters strive for balance in their ecosystems, and a lot of your job in the game involves investigating when the food chain is unbalanced, such as when a monster moves between climes.

Sentient beings can have even more impact, whether it be in their own culture or interacting with others. For my space setting, the Skraks are relatively new to the galactic empires. A lot of their buildings are prefabricated designs from another empire, but the Skraks have modified them with mesh so they can climb around easier—and as a plot point for the novella they appear in, Warp Gate Concerto, their lack of traditional senses means they’re unaware when the protagonists hack into the cameras that come already installed in all those pre-made designs. In later stories I have planned, there’s also a culture whose people slowly petrify as they age, but the culture learns the tapping-speak of the Skraks in order to communicate with those who can no longer speak but can still tap parts of their stone bodies. Little details like this help establish the Skraks as part of an intergalactic society, instead of one race of weird aliens tied up in their own culture.

So sit down, think about your creature and where it lives, and let your mind wander. What do you see your creature doing? How do other lifeforms interact with it? Consider the points above, and you should be able to scrounge up some ideas on how your monster is connected to the world at large of your story.

6. THE POINT OF IT ALL

I hope you had fun following me on this journey, but even here at the end, you may stop and ask, “Why? Even if monsters can be cool, what’s the point of including them instead of real creatures from our own world?” There are a couple of reasons for that, and not just because we don’t have real flying lizards that breathe fire for me to sit down and study.

For me, part of the beauty of speculative fiction is how it gives us an insight into aspects of our own humanity. Fantastical creatures are an extension of that. Seeing the sort of creatures that populate a story speaks to its values, what the people within that world (and the creator of the world outside of it) find important.

Let’s look at dragons, for example. Some stories use dragons as antagonists, and how it’s overcome showcases the character of the protagonists. Bilbo in The Hobbit thwarts Smaug with his wits, while Tiamat and her servants in the Dragonlance series are defeated by, among other things, faith in the power of good in both gods and collective humanity. Other stories have dragons as sidekicks (helping our hero in How to Train Your Dragon discover himself and find his place in the village), part of the setting (a Rathalos in Monster Hunter isn’t going to end the world, but it does bring a village together to protect the area) or even protagonists in their own right (Spyro the Dragon shows how even the young and small members of a society can save it).

Now look back on the creatures you’ve made; what do they say about your world and its heroes? What do they say about you?

Thank you all for following these tracks on your creature-creating quest! I can’t wait to see what all of you come up with. As for me, I’ve got a number of books in that magical first draft stage, so it’s time for me to start this process all the way back at step 1 again.

Resources and books mentioned in the post:

- Elemental Encyclopedia

- Ardulum Series

- Memoirs of Lady Trent Series

- Outlander Series

- Volo’s Guide to Monsters

- Art of Dragon Age Inquisition

- Art of Brutal Legend

I hope you enjoyed this guest post by Dorian. Connect with Dorian through their website and be sure to check out their books Bones and Bourbon and Warp Gate Concerto. Dorian is also on Twitter and Facebook as @DorianGravesFTW – there you can get glimpses of what they are working on, or to show them what sort of monsters you’ve made!

Banner Image

Image of Dragon from Unsplash

Unicorn and Skraks by Dorina Graves.

Be First to Comment