During my teaching degree, I learned about special needs and the different categories in which school systems categorize kids based on the support that they need for being successful in their education. As a teacher, I have to ensure that I meet each of my students where they are, progressing not only them but the class too. Today I have the pleasure of talking to Dan Fitzgerald about being a parent and teacher to special needs kids. In some places, schools have already reopened and I am hoping that this discussion will give you some ideas on what you can do to support your special needs kids, whether in the classroom or at home.

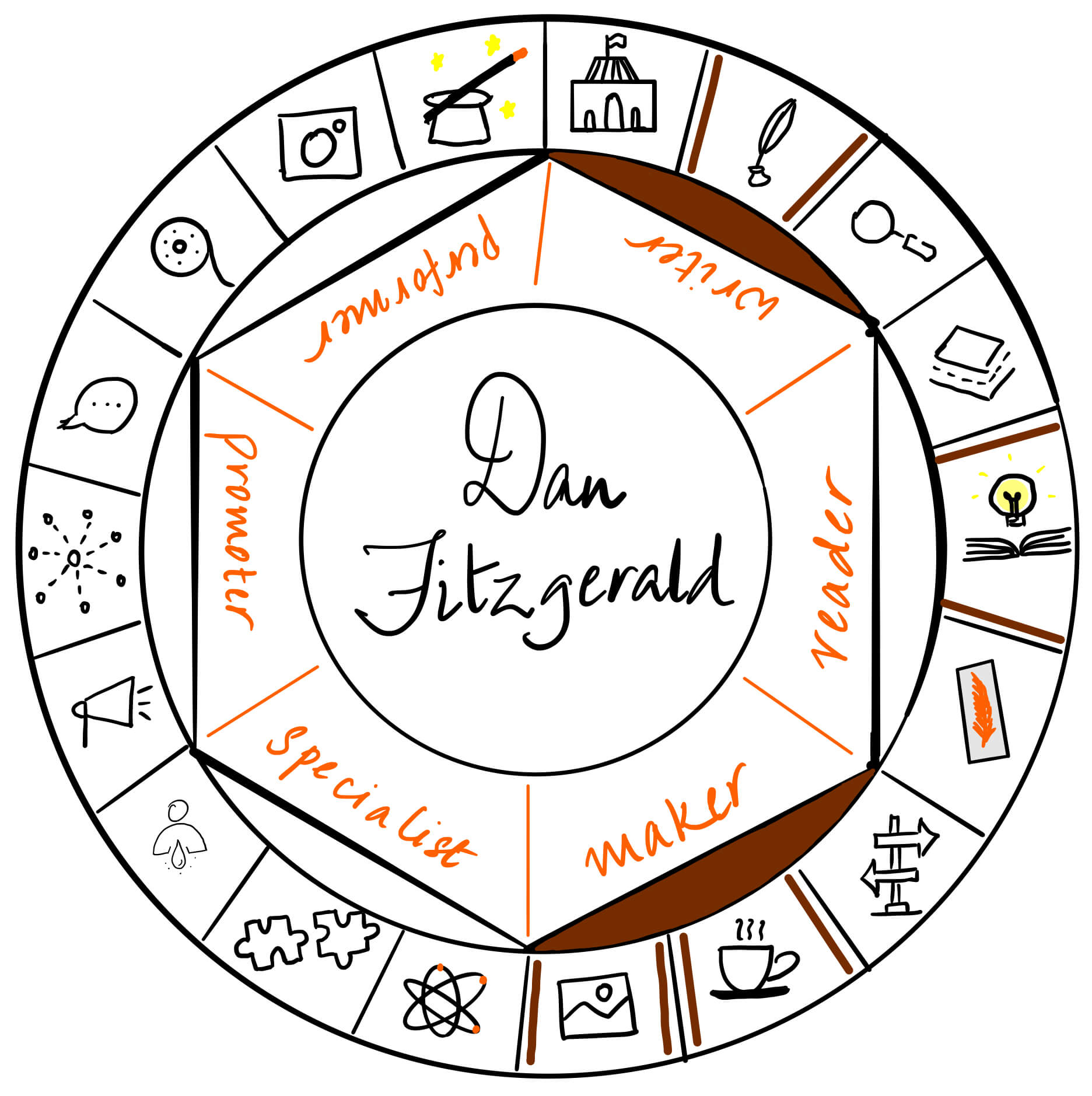

Dan Fitzgerald is a fantasy writer and French teacher living in Washington, DC with his wife, twin boys, and two cats. When he is not writing or teaching, he might be gardening, doing yoga, cooking, or listening to French music.

Dan, welcome to The Creator’s Roulette and for agreeing to talk about this topic! I have been wanting to touch on education for a long time and I am thrilled to get started. What got you interesting in teaching, special needs kids in particular?

I have always been interested in teaching and learning, and have known I would be a teacher of some kind since I was a child. I have been a high school French teacher in Northern Virginia (United States) for over twenty years, and as such, I work with many high-achieving students from privileged backgrounds. For the first part of my career, I did not know much about “special needs” children, beyond the occasional student with ADHD or other relatively minor learning challenges. Of course ADHD can present enormous difficulties for some students, but sadly, students with more severe effects of ADHD are often not enrolled in French or other courses that are considered “challenging.”

As I grew as a teacher, and as language classes became more inclusive, I began to notice students having trouble with organization, with processing language in certain contexts, etc. I started working more with students individually, with their counselors, their parents, and the special education department, to try to help identify the nature of their difficulties. In some cases, I have encouraged students to focus on their core subjects at the expense of French, if that made sense for them, so they could stay on track to graduate. I’ve given students time in my class to work on math, English, social studies, or science, because French is a luxury for most of them, but a high school diploma is not.

At the same time, I became the father of twins, who showed some developmental delays, which grew more pronounced with time. Eventually, they were identified as having mild Intellectual Disability, ADHD, and several other disabilities, all related to a genetic mutation that had recently been discovered. As you can imagine, having children with special needs made me more closely attuned to the needs of my students, and the focus of my work changed. I have made it my mission to help identify children who need additional support and to try to help them get it. Unfortunately, this is often very challenging, but it is among the most important things I can do as a teacher.

What does ‘special needs’ mean? How does the definition adapt based on the setting and your role as a parent or teacher?

Some disability advocates reject the term in favor of disabled, and their argument has considerable merit, but the term “special needs” is common in education, so I will use it here. In the educational environment, “special needs” refers to disabilities that prevent a student from fully accessing the curriculum (a loaded phrase, to be sure). Students identified as disabled must, by law, be given accommodations to help them access the curriculum, which can take the form of extra time, extra help, alternate forms of assessment, smaller classes, etc.

As a teacher, I am legally required to provide accommodations as specified by the student’s IEP (Individualized Education Plan) to help them succeed. Such accommodations can be extraordinarily challenging in a class of thirty students, so I try to be as flexible as I can, to work with the student and their team (parents, special education teacher, counselor, etc) in a variety of ways, with the goal of giving them equal access to learning. It can be maddeningly difficult, and it can even feel impossible at times, given how tight schools’ budgets are and how large classes can be, but we fight the good fight with the weapons we have.

As difficult as all that is, the biggest challenge is not the students identified as having special needs, with an IEP or a 504 plan in place to support them. It is the students I can see struggling, the students who, try as they might, just can’t learn to the same level as their peers without extra support, but who for various reasons are not identified as having special needs. Many times it comes down to cultural misconceptions of what special education is, which I will discuss later.

As a parent, I see the challenges my kids’ teacher faces in trying to help my boys “access the curriculum.” There is this idea of “rigor” in education, with this expectation that all children can achieve equally if we just give them enough support, and it is absolutely not true, and it does great damage to children’s learning. They are required to complete much of the same work as their typically achieving peers, but no amount of support can help them understand fairly complex texts about the Civil War, which neurotypical sixth graders are reading. No amount of support can help them master fractions, when they can barely grasp addition and subtraction.

I know this, and my kids’ teacher knows this, but they have a legal requirement to help my children “access” the sixth grade curriculum, which is heavily influenced by state and federal guidelines, which don’t always make a lot of sense. So we play this game, in which they are given shortened but still impossible texts and sets of math problems and other schoolwork, and we all do the best we can. This is challenging enough in normal times, but in virtual education, it is a disaster. Not the teacher’s fault, not the school’s fault, not the school system’s fault; society’s fault for the way we try to codify and standardize learning.

What are some stereotypes or perceptions that people have about special needs kids? I know we are generalizing here and this is a great opportunity to address any specific ideas that you have found people have.

I want to talk about my kids first. My children have intellectual disability, among many others, and there are many things their typically developing peers can do that they are just not capable of doing, or understanding, due to their disabilities. Complex math is one of them, as is a lot of what goes on in social studies, science, and reading. But there are some things they can do at age 13 that might surprise people, given their diagnoses:

- One of my kids has read Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

- Both of my kids have average or above average vocabulary for their grade level.

- One of my kids can identify most common neighborhood flowers and most vegetables in our community garden.

- One of my kids correctly identified a swallowtail butterfly caterpillar from its color patterns alone.

- One of my kids can memorize songs and sing more or less in tune..

You get the idea. This is not what we think of when we think of intellectual disability. Disabilities are not monolithic. People can have profound challenges in one area and excel in another. I’m fine if my kids will always be weak at math and struggle in social studies, if it means they can read books. And if they couldn’t, that would be fine too. I’d want them to be happy, to learn what they can learn, and to remain curious about the world, to always want to learn more. Just like what any parent would want for their kids.

When it comes to special needs and special education in schools, whooboy. This is a huge topic, but I want to focus on some cultural misconceptions among the parents of special needs students, the biggest of which are :

- My child is not disabled. They’re just lazy.

- It’s going on their permanent record.

- Teachers are going to hold it against them.

- They’re going to be put in a special class with kids who can’t learn.

- They can’t take college preparatory courses.

- ADHD is a myth.

While I don’t have time to address all of these, there are several main points I would like to make.

One is that parents are often the biggest obstacles to getting children the help they need, typically due to their misconceptions about special education. Special education guarantees a child certain supports, and nothing else. It does not label them, limit them, ostracize them, or otherwise have a negative impact. The supports are not always perfect, and as I mentioned above, they do not always guarantee an excellent outcome, but they are protections against a child being left out. Parents sometimes see a child with special needs as a reflection on their performance as parents, and refuse to get their child the help they need, which helps exactly no one.

Another point is that outcomes for special education are worse for students of color and students living in poverty. Sadly, many parents from developing countries have understandable hesitation about special education, given the state of special ed in their countries of origin, and we need to do a better job as an education system on outreach to these families. Students whose parents have been the victims of systemic discrimination, i.e. people of color, may also be hesitant to trust in a system that discriminated against them. The legacy of special needs students being segregated and warehoused feels eerily similar to the historical segregation of education based on race. We have a long way to go to rebuild the trust in our education system so everyone feels equally represented and supported.

My kids are relatively lucky. They have two college-educated parents, a house full of books, and access to many loving adults. We are able to get them a private reading tutor, to take them to museums and for walks in the forest, and provide them a rich linguistic and cultural environment. Not every special needs kid has those advantages, and you better believe it makes a difference.

I grew up in India where grades and standing in the class are paramount, more so than sports or any other extracurricular activities. It is a very competitive environment. Before your kids were born, did you have certain expectations of your future kids in terms of education? How did you adapt and come to terms with who they are and what they can and can’t do, now that you know them? This links to the misconceptions that parents have about special needs kids and I am wondering how you worked through them as a parent.

This has been a real challenge. Both my wife and I have multiple masters degrees and speak several languages. We started raising our kids in German, since we both speak it (my wife much better than I, but I am a language teacher by trade so I can ramp up quickly). We expected to raise multilingual kids who would go on to equal or exceed our education and world experience. When their language delays became apparent (neither one spoke a word before 18 months), we stuck it out with German for a time, though some people blamed their delay on our choice of home language. There’s this misconception that multilingualism causes language delays and is somehow bad for kids, and as language teachers you can imagine how we reacted. A large portion of the world is multilingual, and research suggests it ultimately makes people more proficient in their home language, and conveys many benefits besides. But at a certain point, we had to recognize that their delays were global, and so we switched to English only at home.

Once their diagnosis of intellectual disability was confirmed, and their development had been measured over time in a variety of ways, it became clear that they probably wouldn’t have the educational future we had expected. It was a lot to process, and there is a kind of grieving process for the child you always imagined, and it took time to accept and appreciate the children we have. The reality was clear: they were making about 50% of the intellectual progress of typically developing children, fairly consistently over time, though in some areas they were, and are, more advanced, and in others less so. But no one wants to say what that will look like in the future, partly because no one really knows, and partly because they don’t want to say it out loud. But it’s hardly common for a person with an intellectual disability to earn a PhD, so you have some ideas.

Two quotes stand out from our many developmental specialists through the years. One doctor bravely told us that though there is no crystal ball, children with their type of disability can expect, on average, to end up with a 4th grade reading level. Do the math: if the brain is fully developed at, say, 20, and they develop at 50% the usual rate, that leaves you with the reading level of a 10 year old. It pretty much lines up. It was very hard to hear, but it also gave us some guidelines for what to expect, and told us what we needed to work on, because reading is incredibly important to us. My wife and I are both big readers, and I am a writer, so we know we want to raise readers, so we fill our house with books, we read to them every day, we hired a reading tutor, and we reward them for reading. They may never read William Faulkner, but they are going to read as well as they are able. My greatest hope is that they will someday read this and take me to task for what I’ve written about them.

The other quote, an offhand statement by someone doing a developmental test, was this: There is no word to describe what these children are. You can list their diagnoses, you can define their scores on various metrics, but none of that captures their essence, or who they are as people. They each have their strengths and weaknesses, yes. They each have difficulty at some things and relative ease with others. But they are not defined by their abilities, or by their disabilities, any more than I am defined by my reading level, my cognitive processing speed, or my spatial abilities.

Basti is super curious about nature, particularly insects, which he studies with great interest. He often refers to his bug friends, and talks about them as if they were real people. He asks a million questions about everything we see on walks, from the flowers to the animals to the rocks and stones. He likes to read about animals and insects, and he studies the pictures in such books with great interest. He makes up stories as we wander, asking me to play the role of the villain in the story, or to be a hero alongside him. He’s not much for reading chapter books, but in every interaction, he seeks to engage the world and the people around him in stories. The divide between fiction and reality is a tenuous one for him.

He is very particular about food; he hates mushrooms and seafood but loves to guess what herbs and spices are in his dinner. He can identify the spices better than some adults, and he knows what he likes and doesn’t like, and doesn’t hesitate about telling me. He loves to swim, to play with any kind of toy, to draw endless pictures of battles between characters he knows from books or TV. Yes, like most kids, he loves video games and TV, but TV plays a different role in his life than for most kids. He jumps around as he watches, his eyes filled with delight as he re-watches his favorite episodes, then later role-plays what he sees and quotes what was said. He has never sat during an episode of a TV show or a movie in his entire life. He often correctly uses phrases we never would expect him to know, and we realize he got them from a show he watched. He’s not just mindlessly entertaining himself; he’s learning.

Fitz shares Basti’s love of stories, from TV or movies or books, but he fetishizes books, and reads them as best he can. He has powered his way through several full-length novels, and he loves his Kindle, which he carries like a sacred object. He often has a hard time sticking with one story, so like many adults, he often has multiple books going at one time, and he switches between them as his whim dictates. When he finishes a book, he knows we will get him another, and a prize, be it a toy, a stuffed animal, a costume, or a scrunchie. At the moment he is obsessed with girls’ accessories, having just spent several weeks with his cousins. Whereas Basti has a deep sense of boy vs. girl, Fitz enjoys a lot of traditional “girly” activities, which we certainly don’t discourage. He wants to be like the people he loves, and he thinks girls are really cool.

Fitz will eat almost anything under the sun, with gusto. He is less discriminating than his brother, and there are few things he doesn’t like to eat. He also loves music, and is obsessed with some of the songs from his favorite TV show. He will look up the lyrics, print them out or write them down, and go around singing them. Sometimes he writes his own little songs, and goes around singing them. And speaking of writing, he is always curious about my writing activities, and always wants to write his own books. So he scrawls them out on white paper, or types them on his laptop, and shares them with me. He is very much a child of words, and he loves talking to other kids. Though they often don’t know what to make of his unusual ways, other kids often enjoy playing with him, and he makes friends at school, and spends hours talking and playing with his cousins.

Why am I telling you all of this? Because this is who they are. They may not be the children we imagined, but they are not just the sum of their abilities and disabilities. They are people, with as many tastes and nuances and quirks as anyone else. Will they go to college and get a degree? Probably not, but who knows? And more importantly, who cares? What I want for them is the chance to live a fulfilling life, to follow their passions, which they have, just like anyone else, to engage their curiosity, and to never stop learning.

I have long ago given up worrying about their future in the same terms of many of my friends, whose kids are taking those steps toward high school and college and careers that we all take for granted. And those things are important, but they’re not equally important for everyone. And when you get right down to it, what defines you more: your college and career choice, or your passions? I could be a programmer or a truck driver or a sociology professor, but I would still be a reader and a writer and a cook and a nature lover, because that’s who I am. All I want for my kids is for them to be defined by what they love, rather than how society decides they should be measured.

What kind of special needs kids have you had in your classroom? As a student teacher, before my assignment to schools, I used to worry about how I would support special needs kids in my classroom along with everyone else. What was it like your first time in the classroom with special needs kids?

The most common situation I see is a child who struggles with organization and executive function, either as the result of ADHD or of a learning disability, whether identified or not. They are often able to learn well when presented material in an organized way, with sufficient one-on-one assistance as required. The problem is that with large class sizes and increased workloads on teachers, school staff, and parents, it is very difficult for students to get the one-on-one assistance they need. I can offer to work with students after school or during their remediation period, but in reality very few of these students are able to take advantage of such help. I have tutors available after school and during remediation periods, but students rarely come for help because they are so overwhelmed with seven classes and catching the late bus home and family obligations and so much more.

The first child I know of in my classroom with special needs was when I was teaching English long ago. The child was bright, and though they had some learning challenges, they had learned many workarounds, and they were among the most capable students in the classroom, largely because of the support of their parents, who had never given up on them. At the same time, their parents held them back due to their religious convictions. They were not allowed to read The Iliad or The Odyssey, which were part of the 9th grade curriculum, because they dealt with what the family’s religion deemed “witchcraft” or “satanic influences.” I had to give the child an alternate text to read, and while the rest of the class struggled with these difficult texts (it was a high-poverty school and most students were reading well below grade level), this child sat there, listening, raising their hand, then lowering it, because they weren’t supposed to learn about such things. It was heartbreaking.

The most memorable student I had was a student with intellectual disability, who worked harder than anyone else I have met to learn French, and they still struggled to retain the most basic information we learned. I worked with them many times, and many tutors worked with them too, and in the end, they earned a C, which was so impressive because it was like an A+ in terms of what they were capable of. I’ll be honest: I gave them a B, though we’re not supposed to do that.

I get it. We are the kids’ cheerleaders and we see the amount of hard work and effort they put in. There has to be a way to present that, but sadly, it all comes down to letter grades and GPAs.

What are lessons you have learned as a parent to special needs kids that you apply to your teaching profession? At the same time, how has teaching helped you as a parent?

The most important thing to know about helping special needs children learn, be it at home or in the classroom, is the same thing one needs to know about helping any child learn. Get to know them as a person, show that you care, and listen to them. Children (and adults) learn in large part because of the relationships they develop with their teachers and parents. If they know that you see them, that you see their struggles, they will work harder, and they will learn more. They may not always learn as much as they, or you, or their parents, would like, but what they learn will matter to them, it will help them believe in themselves, and it will help them learn other things in the future.

When I see a child who doesn’t do well in my class because the material is just really challenging for them at that point in their life, I make sure they know that I care about them. I care about the manga they read. I care about the cars they’re into. I care about the bangles on their bracelets. I care about the doodles they draw, the music they listen to, the sports they play. All of that matters, and frankly, I don’t care all that much if they learn French in the specific time they are in my classroom. I mean, obviously I do care if my students learn French, but they can’t do that if they don’t believe in themselves, if they don’t feel worthy, or seen, or cared for.

As a parent of my particular children, it can be challenging to have a conversation with them when all they want to talk about is a show they watched, when they want me to repeat lines they enjoyed, to play the role of a character I have never seen, to say the same things over and over again. But I know how important it is, and so I do my level best to give them my time and my attention. Seeing how important that is to my students has helped me be more patient with my own children. Sometimes I’m too tired, or too world-weary, but I do try, because on some level, whatever imaginary play they’re engaged in has value to them, and is helping them develop their brain, no matter how difficult it is for me to see at the time.

With the current pandemic situation and schools looking at remote delivery, what are some resources that parents can look at to support their kids’ education at home? You are welcome to answer this in the context of special needs and in general.

Parents need to look at their children’s education as being an equal partnership between home and school. Parents provide the stability, the care, and the intellectual/linguistic stimulation children need to learn, and school takes it from there. Sometimes an individual teacher will do a better or worse job in pushing the child’s learning forward, but ultimately a child who has a supportive, intellectually rich and diverse home environment will do well in the long run. What they do or don’t learn in a school in a particular class or a particular year is less important than what they learn in eighteen years at home.

So I would say this: do the best you can, but don’t panic if a student doesn’t do as well in online school. Keep them safe, keep them sane, keep them curious, keep them interested in what life has to offer. Talk to them. LISTEN TO THEM. Even when it’s hard. Especially when it’s hard. This matters more than any specific support or resource in the world.

There is one resource I would like to mention, besides the attention of parents and other adults in children’s lives. And that is BOOKS. I would rather have my child read books of their own choosing, at their own pace, and in their own way, than most of the work they get in online school. And yes, I read to my kids every day, and it’s a habit I try to instill in them. In fairness, one of them is less inclined to reading, and has a harder time with it, and reads less, but he still reads, studies, and examines books.

There are some things kids can’t get through a screen, especially children with special needs. Fortunately, they can get a lot of those things at home. And quarantine won’t last forever. When it’s over, when they finally do go back, they need to be happy, and curious, and hungry to engage. Which they won’t do if they’re breaking their heads over work they don’t have the skills to do on their own. As a teacher, I try to keep this in mind, even as I work my hardest to give my students lessons and outside work that will keep them engaged. And as a parent, I will try to keep in mind that my kids are kids, that learning does not only happen through school, and maybe not even primarily through school.

In an impossible situation, we need to accept our limitations, and give what we have to give with all our hearts.

Have you listened, really listened, to a child recently?

I hope you enjoyed this conversation with Dan, and it was as meaningful to you as it was for us! You can connect with Dan on his website.

Banner Image: Photo by Agence Olloweb on Unsplash

Images in order of use in the article:

Photo by salvatore ventura on Unsplash

Photo by Brian Garcia on Unsplash

Being an author and a single parent to a child with special needs (now an adult as she’s about to turn 19), I deeply appreciate this post! Thanks Kriti and Dan!

Thanks for reading Camilla 🙂

You’re welcome, Kriti!

[…] Indie Recommends Indie and today I have author Dan Fitzgerald with me. You might remember him for our conversation on Creator’s Roulette last year or more recently, the cover reveal for his latest book, The […]

[…] sharing my little pieces on Instagram. Author Dan Fitzgerald, who you met when we chatted about special needs kids, really liked some of my pieces. He commissioned me to make one for his book and today is the cover […]