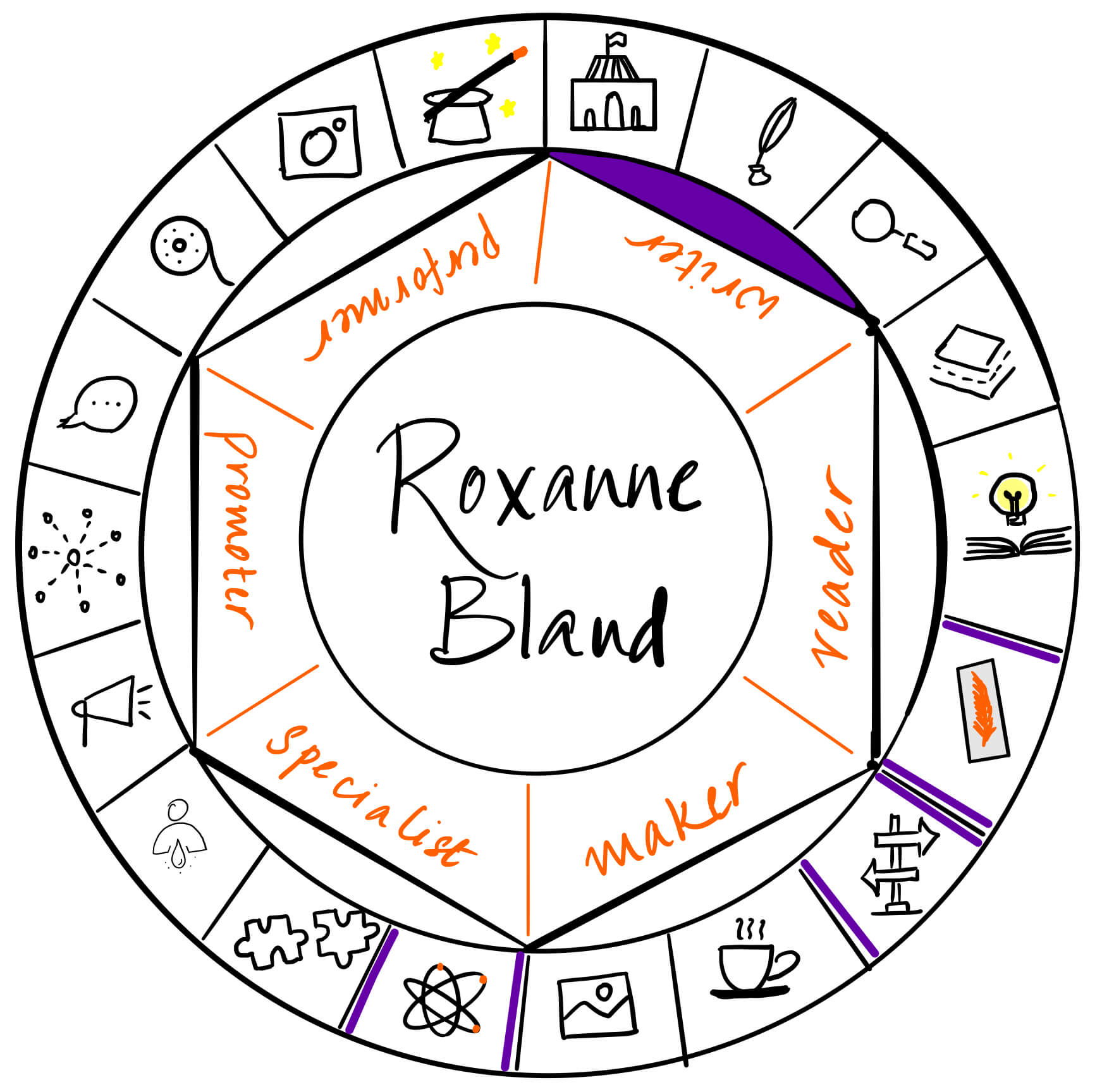

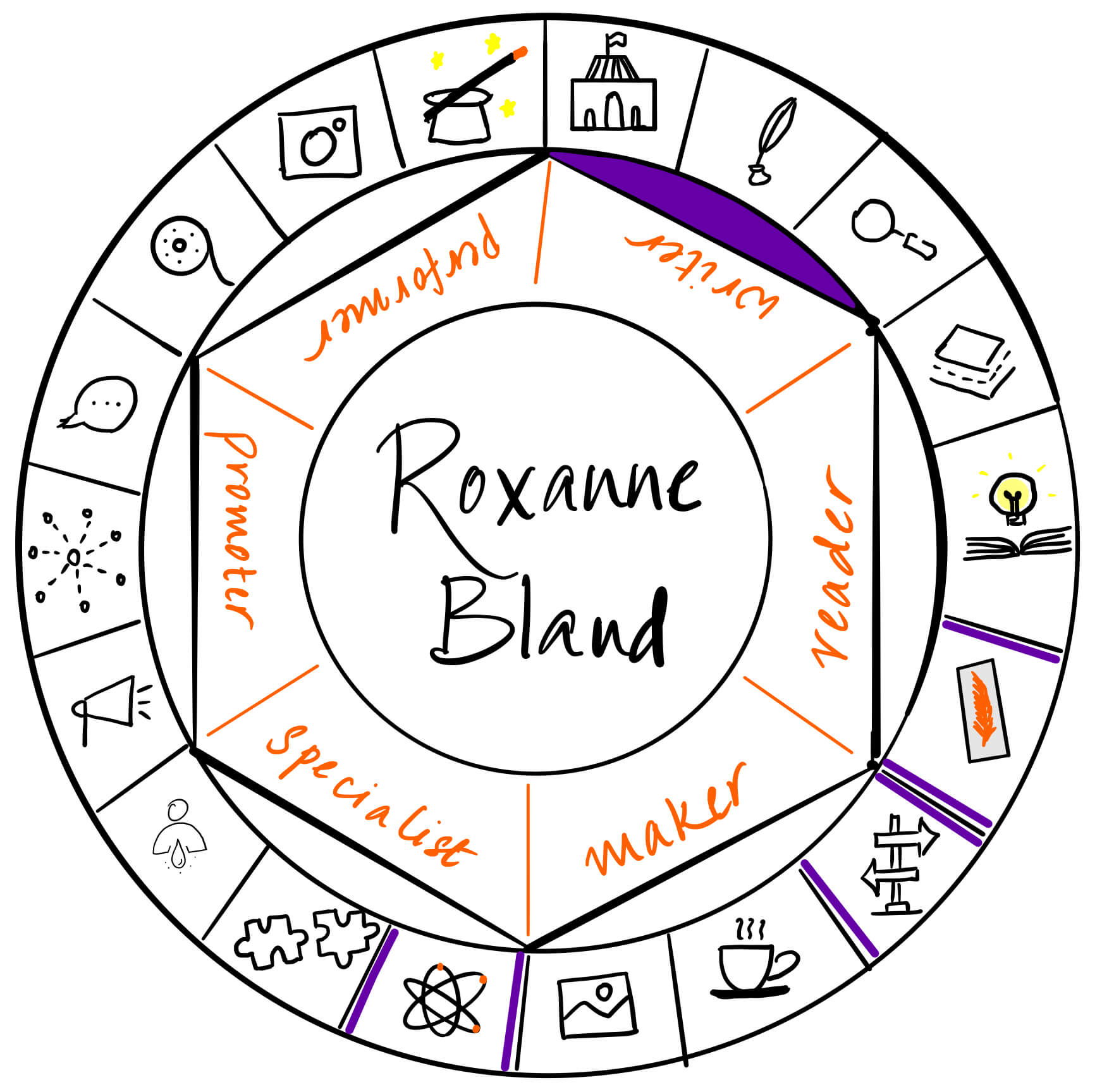

Two of my favorite genres to read in Science fiction are dystopia and post-apocalyptic stories. I love the themes that both these sub-genres portray. For example, Firewalkers imagined a future in which global warming has made living conditions very hard and the regions around the equator have become desert. The Warehouse touched on factories that are the size of cities and the control of one big multinational corporation on the economy. There are themes around survival, human interaction, greed, privilege and much more, in all these books. I have Roxanne Bland with me today on The Creator’s Roulette to tell us more about what it means to root science fiction in reality.

The science fiction and fantasy genres have been used by writers as vehicles for social and political criticism since their inception. Fantasy’s credentials go back to classical times, if not further. Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels was a fantastical satire of the politics of his day, including King George I’s royal court. George Orwell’s 1984 depicts a world of perpetual warfare, continuous surveillance, mind control, and psychological manipulation. Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World shows us a world that appears to be a utopia—poverty has been eliminated—but the reader soon learns it is not. The population is regulated, and there is a strict hierarchical social structure where behavior is also regulated. In other words, a good chunk of free will has been lost. Other stories are critical in a different sense, that is, they are explorations into what society might be like if our norms didn’t exist. Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Left Hand of Darkness shows us what a genderless world might be like, where the gender norms that characterize our society have no meaning. To be sure, science fiction and fantasy is also rife with stories of pure escapism—space operas, adventures featuring swashbuckling heroes, duels with dragons, and more.

C.M. Kornbluth, in his essay The Failure of the Science Fiction Novel as Social Criticism, says (and it is worth repeating here):

“In this essay I have tried to show that science fiction novels, on the record, have not been measurable effective social criticism. I have speculated that the reason for this is sort of an embarrassment of riches—that nothing in the science fiction novel is what it seems, that there is no starting point for social change resulting from social criticism. As social criticism the science fiction novel is a lever without a fulcrum, a single equation with two unknowns. The science fiction novel does contain social criticism, explicit and implicit, but I believe this criticism is massively outweighed by unconscious symbolic material more concerned with the individual’s relationship to his family and the raw universe than with the individual’s relationship to society.”

Kornbluth points to novels like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was certainly a catalyst for the U.S. Civil War, and Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, which brought about sweeping changes in the meatpacking industry. I do not disagree with his sentiment that these novels had a tremendous social impact on life in America. Yet I think these novels, like so much else in life, are happy accidents of history. Stowe, like her father. the Reverend Lyman Beecher, had been an abolitionist. In 1832, she moved to Cincinnati, Ohio with him, and it was there she first encountered runaway slaves and learned about the Underground Railroad. At that time, the politics that would eventually erupt into the Civil War was just starting to heat up. Stowe published her first novel in 1843; Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in 1852. What if Uncle Tom’s Cabin had been her first novel, published 18 years before the war began? By 1852, the battle lines had been drawn, and the war was just 9 years away. Would Uncle Tom’s Cabin have had the same impact in 1843?

Likewise, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, was published in a single volume in 1906. Historians disagree on when the Gilded Age ended, with various dates given, ranging from 1896 to 1901. Whenever it ended, in prior decades European immigrants had poured into the U.S., searching for higher wages and a better life. Some found work with decent pay in the industrialized cities. Many more did not, and lived in abject poverty. By 1906, the Progressive Era was in full swing, and Americans were taking note of the immigrants’ plight. If The Jungle had been written during the height of the Gilded Age, with its excesses and the political power of the moneyed class, would anyone have taken notice, much less done anything about it?

For sure, we will never know, and can only be glad these novels effected the changes that they did. As for Kornbluth, he might even be forgiven, considering he wrote his essay in 1959. The science fiction and fantasy genres have greatly evolved since then, with deep changes he did not live to see.

Even if we agree with Kornbluth that science fiction and fantasy have not engineered the profound social changes exemplified by Uncle Tom’s Cabin and The Jungle, but have nevertheless provided social and political criticism, there are those writing today who complain the genres have lost their edge, and science fiction, at least, is becoming irrelevant. In his article Should SF Die? Jetse de Vries points to authors Ashok Banter, who observed that science fiction is morally bankrupt; Lavie Tidhar, that science fiction and fantasy is suffering from monolithic Anglophone syndrome; Mark Newton, that science fiction is dead and fantasy is the (bestselling) future; and Athena Andreadis, that science fiction has ditched science and has become, in effect, fantasy. Of his own opinion, de Vries says (again, it is worth repeating):

“My viewpoint is that SF is becoming increasingly irrelevant, and that lack of relevance can be attributed to developments and trends already mentioned in the points above, and SF’s unwillingness to really engage with the here-and-now. That doesn’t mean that SF needs to die (actually, a slow marginalisation into an increasingly neglected and despised niche-cum-ghetto is probably a fate worse than death), but it does mean that SF needs to change, and that it needs to become much more inclusive of the alien (and I mean alien in ‘humans-can-be-aliens-to-each-other’ sense) and proactive, meaning it should not just shout ‘FIRE! FIRE!’ (and do almost nothing but), but both man the fire trucks *and* think of ways to prevent more fires.”

Ebonstrom (username) made similar observations in their post Science Fiction and Social Awareness. Writers aren’t willing to take risks, to write about social/racial inequalities, to write about future issues that might arise due to scientific complexity. Modern science fiction “fails to acknowledge writers from other minority groups who may have different views of the future;” “the rewarding of primarily white men as the best writers of the genre and as the main protagonists;” “the increasing marginalization of the genre due to lackluster efforts of writers to explore more risky ideas;” and “the lack of scientific interest in the potential audience which reduces the potential quality of the story.” Ebonstrom also points to the growth of stories set in a dystopian future, instead of looking for ideas to promote a positive one. Most of all, Ebonstrom complains about the loss of “science” in science fiction, an unwillingness to explore scientific ideas, so that science fiction stories are not so much “science fiction,” but westerns or fantasies set in space.

I certainly agree with some these points. The science fiction and fantasy genres ARE dominated by white men and usually have white protagonists. For the most part, POC writers have been ignored, as have LBGQT+. Perhaps science fiction and fantasy characters should look more toward each other. The various clans in science fiction and fantasy, and by that I mean the races, gender, religious affiliations, and every other difference that humans seize upon, should look at their “alien-ness” and work toward mutual understanding. In so many stories, race and such is glossed over, “we’ve already solved that problem,” and there are very few stories that show how it was done.

As for the lack of “science” in science fiction, there certainly don’t seem to be very many Larry Nivens around anymore. It has been said that the lack may have something to do the breakneck pace of technological development. What was mere imagining two decades ago, or even a decade ago, is reality today. In the time it takes to write a book, at least for those who toil for years rather than months, technology may have gone beyond what the author had imagined. In two of my books, I imagined a communications module where the user accesses the machine by connecting to it via the central nervous system. I imagined a spaceship where the pilot can connect the same way and control the ship by thought. I imagined a quantum transmitter/receiver, allowing for real-time communication between galaxies by harnessing the power of entangled particles. As for the first two, for all I know the technology exists, though I suspect if it does, it’s a military secret. I know the last doesn’t exist, because according to information theorists, the message would necessarily travel faster than light and Einstein wouldn’t like that. Moreover, because it doesn’t comport with what is doable given the existing science, some might classify it as fantasy. Though there is some truth regarding the pace of technology, I do not accept that as a reason for the lack of “science” in science fiction. Futuristic, whiz-bang gadgets for the sake of futuristic, whiz-bang gadgets does not science fiction make. What I do accept, is that much of the science and scientific methods practiced today will have a place in the future. In medicine, a syringe is a syringe. Injections might be given with a different tool than what we use today, but whatever that is, it will still have a needle to break the skin. Why should the presence of a syringe in a science fiction novel make the book “bad science fiction?”

I also believe there is far more risk-taking in science fiction and fantasy than the above commentators think. It appears they are looking at just a narrow slice of the whole book market—the mass market, made up of traditionally published authors. They are not looking at the smaller markets, and the authors traditional publishers have ignored. They are not looking at the market made up of independent presses and independent authors. They are not looking at the books that do not have access to wide distribution channels that would make them readily available to science fiction and fantasy readers. But the authors and books they bemoan having disappeared from the genres definitely exist, and they deal with subjects that are here and now. I am one of them, and I know of many others. Here’s just a small sampling:

- Alma Alexander, The Second Star, Were Chronicles (Random, Wolf, Shifter) (December 2020)

- Beth Barany, Into the Black

- B-Cube Press (anthologies), Alternative Truths, More Alternative Truths, After the Orange: Ruin and Recovery, Alternative Truths Endgame

- Kathy Bryson, Feeling Lucky

- Penelope Flynn, The Chronicles of the Renfields: Regarding Koescu, Revenant Lineage Book 1

- Laurel Anne Hill, The Engine Woman’s Light

- Tenea D. Johnson, R/evolution, Evolution (Revolution Books 1 and 2)

- K.C. May, Inhuman Salvation

And, of course, me: Roxanne Bland, The Underground (The Underground Series, Book 1)

For those who lament the failures of the science fiction and fantasy genres today, I have one simple piece of advice: Open your eyes. And then you will see.

Do you, as a reader, believe Science fiction and Fantasy have become irrelevant in helping us to dream and hope for a better future?

I hope you enjoyed this guest post by Roxanne! Find her on her website, blog, and YouTube.

Banner

Now I know what I must do–write more and publish it!