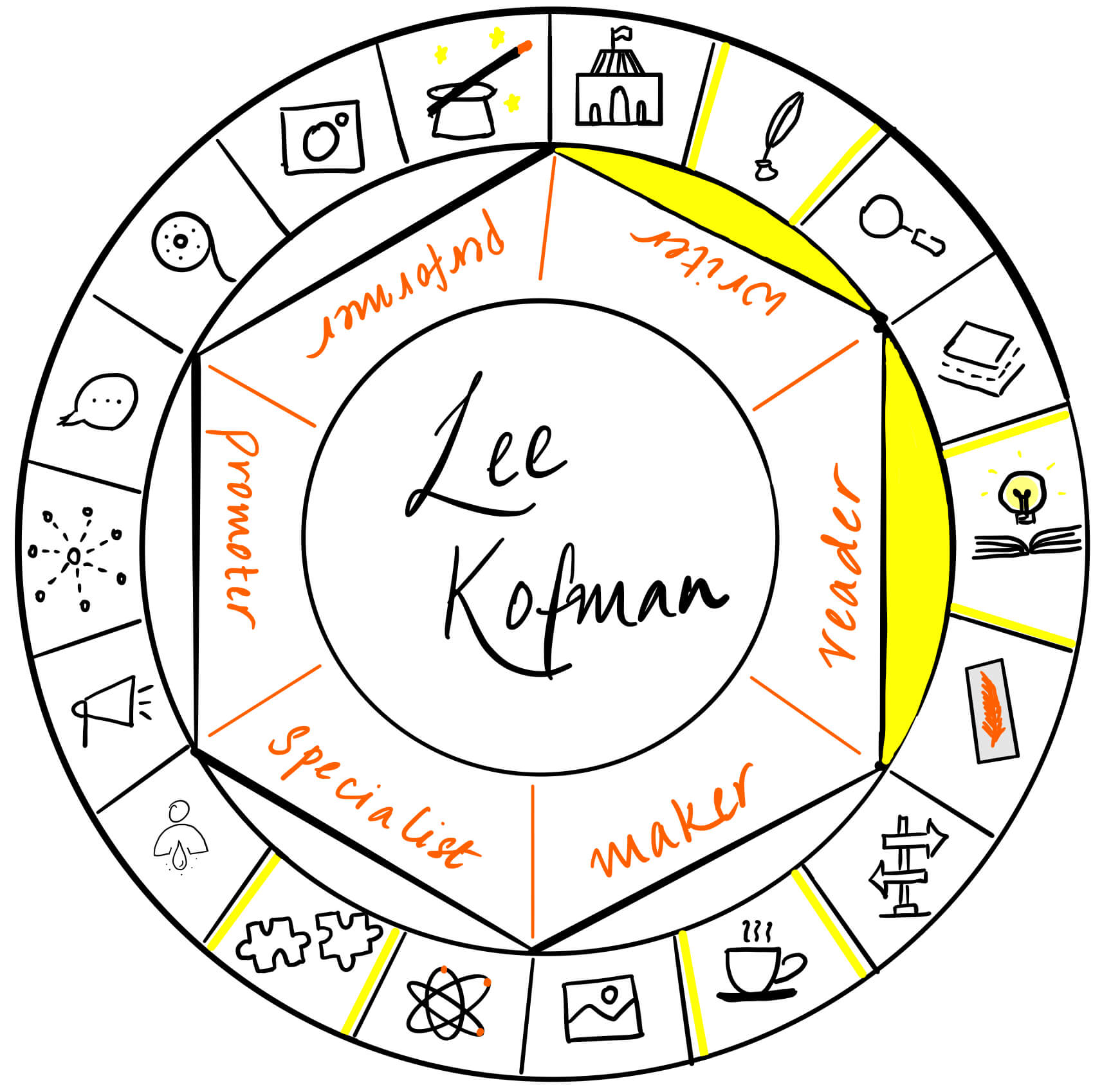

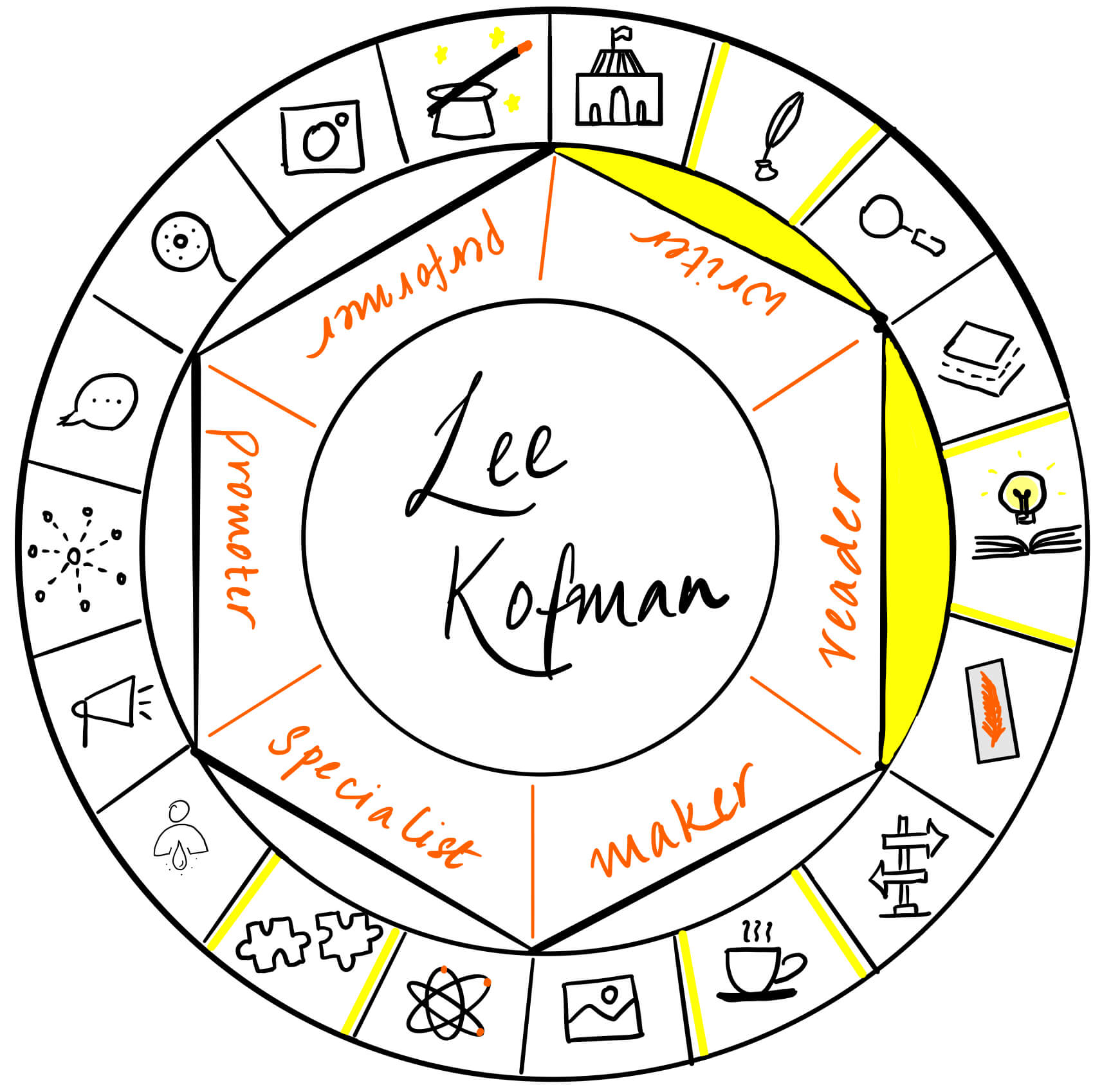

I organized my bookshelf the other day to bring all my review hardcopies to the front so that I could start reading them. Imperfect by Lee Kofman spoke to me when I was looking for a new book and that started a journey in understanding scars and mutilations on the human body in a manner that I have never explored before. Lee’s book is full of personal stories as well as academic research and you would know how much I love a combination of those. For this 50th Creator’s Roulette, I am excited to bring you this interview with Lee about body image and its representation in fiction and popular media. Similar to how Allison Alexander’s book opened my eyes to the representation of disability in fiction, Lee’s book sheds light on scars and the body.

Welcome to the Creator’s Roulette, Lee! What led you to pursue research about the body and its effects on who we become?

Kriti, thank you for having me here. As you indicated already, Imperfect is a work based on a decade-long research I conducted, but at its heart it is a deeply personal book, and I’ve carried it inside me a long time before I began doing this research. The book, a narrative nonfiction, is framed by my own story of having many disfiguring scars.

By the time I was eleven, I had undergone numerous operations on a defective heart and on injuries I received when a bus ran me over in a drink-driving accident. I’ve always felt that my body, scarred as a result of all that, has impacted my life choices, and even my personality, deeply.

But when I was growing up as a young woman, and in my later years too, I couldn’t find any books that reflected my experiences, nor female role models to show me that I’m not a ‘freak’, that there are other people with what I call (ironically, of course) ‘imperfect’ bodies, who live rich and fulfilling lives.

Especially in my youth I was desperate for some normalizing of my experiences, and also for practical advice on how to manage best in a body that is considered to be outside of a social norm, but couldn’t find anything. So in recent years I decided to write my own book.

Then, four years ago, to do this became even more urgent after my second son was born and was diagnosed with albinism. Many people with albinism have very fair skin and hair. Ollie’s skin and hair are fair but not to the degree that attracts curiosity. He does, however, have another visible difference common amongst people with albinism – nystagmus, an involuntary eye movement sometimes poetically called ‘dancing eyes’. His diagnosis spurred me to expand my theme and write a book not just about scars, but about any kind of ‘imperfect’ body – for example, larger people, people with dwarfism or even with extreme body modification. I want Ollie to grow in a society that is more aware of the impact of stigma on people who don’t fit the so-called norm, and I hope this book will make some small contribution to the public conversation about the role our appearance plays in our lives.

Thanks for sharing your story and motivation, Lee. Stories have immense power. You mention Body Surface in your works. How is that distinct from the concept of body image?

Body image is a complex concept, but at its most basic level it refers to how we feel about our own bodies – do we have ‘positive body image’ or ‘negative body image’. One of the things I argue in Imperfect is that currently when we discuss appearance and how it impacts our lives, we predominantly discuss it in terms of body image, and this isn’t always helpful. If someone is not happy with their body, we say – they need to have a better body image. So the emphasis is on what this person needs to do. Now, of course it’s important to work on our own feelings. But, as a society, we need to talk more about how each one of us contributes to other people’s so-called body image. For example, as a woman with dwarfism in my book says, it doesn’t matter that much how much she ‘works’ on herself to feel good about her body, because when she walks on the street and people shout abuse at her, or when men refuse to date her because of her height, it is hard to stay positive.

So, in Imperfect I focus less on the question of how we can improve our body image (there is plenty of literature on that out there, and it’s not always helpful either) and look more at how we make up stories in our minds, often subconsciously, about what others are like based on their appearance. For example, if we see someone with numerous tattoos, piercings and subdermal implants, we’re likely to think this person is mentally ill or a criminal. But I, for example, interviewed an extremely modified woman who was about to start studying social work, and was averse to drugs and into animal rights. To narrow down the focus of my examination, to make it manageable, I coined the term Body Surface that stands for the appearance of the body itself. So I wasn’t exploring, for example, how clothes or hair color affect the kind of stories people tell themselves about us, but only the (more or less) permanent features of the bodily appearance, so the flesh and skin – the surface.

Physical scars originate from a variety of reasons, including childbirth, wounds, and cultural rituals. In your research, did you find that scars for men and women differ?

Yes and no. Both men and women with scars (disfiguring scars) are likely to be stigmatised. People may think upon seeing a scarred person that this person has a tragic life, that they must be lonely and depressed. But we’re more likely to have criminal associations with male scars. Men with facial scars, for example, often say strangers get scared of them. Men, though, also have more chance than women to be viewed as attractive if their scars are only mildly disfiguring. For example, Harrison Ford’s chin scar has never prevented him from being a sex symbol; it was even incorporated within his Indiana Jones character’s story. Whereas Sharon Stone who has a (fine) neck scar used to meticulously cover it on screen and in real life – with scarfs, clothing and jewellery – so that presumably not to spoil her beauty.

Representations of the Body

How does reading and watching a certain Body Surface affect the mind?

People are storytelling animals and our cultural stories – be these works of literature, television series or reality tv shows – affect deeply how we view the world. So, for example, if we repeatedly watch body makeover tv shows where contestants say they want to undergo gory plastic surgeries, and demanding diet and exercise regimes in order to better their selves, then this idea that a more beautiful body equals a more beautiful mind can stick with us. And if we watch shows like The Biggest Loser where larger people are routinely humiliated, then we may absorb – often unconsciously – the idea that big people are ridiculous. Representations matter deeply. They also matter in positive ways. For example, my son has been wearing glasses since the age of two because of his albinism, and at that age he was the only bespectacled child in his childcare. I still recall the joy he felt when we walked one day into a toy store and he saw a Harry Potter doll with glasses. He was so excited, and probably relieved too, to see another small child ‘like him’.

What are some misconceptions or misrepresentations you have found about scars and mutilations in fiction and popular media?

Firstly, there is little representation of characters with mutilations in our popular narratives, and I think this has a lot to do with the fact that we’re a less religious society, which, understandably, also means our fear of death is more intense, and so too our faith in the powers of modern medicine. But mutilations highlight the limits of medical potency and remind us of our animal, and therefore finite, nature. And when we do have characters with scars or other mutilations, such as missing limbs, they are usually portrayed either as evil or as miserable, tragic characters. And yet, as in real life (and the real and symbolic lives usually feed into each other), for men with scars there seems to be a little more room for alternative, more positive representations. The violence associated with mutilated flesh sits easier with how we traditionally understand masculinity – an active, risk-taking state of being. To some extent, man’s ravage is something to be expected, even admired. As long as it’s moderate, of course.

In popular culture’s unwritten laws, severely disfiguring facial scars on men signify evil, you see this for example in the long tradition of depicting Nazi characters with such scars. But milder mutilations are more ambiguous and can occasionally belong to the good guys, sometimes even enhancing their appeal, like in the case of Tarzan. Female scars, though, are often depicted to be self-inflicted, evidence of a wounded psyche, mental instability. Or they might be inflicted by men and then signpost victimhood.

What are some positive representations?

I’m happy to say that increasingly, there are more of them now. Game of Thrones, for example, tells nuanced stories about a man with dwarfism, a larger man and a burn survivor. These characters aren’t demonised, idealised, or de-humanised in some other way; and the series’ makers do not shy away from showing that Body Surface has mattered greatly in the lives of these characters, but without overshadowing all else. The new blockbuster Mortal Engines features a female protagonist with facial scarring. Graeme Simsion’s recent novel The Rosie Result has a complex and agentic character of a girl with albinism. I hope to see more of such stories around.

How did your own Body Surface shape your life, be these your sense of self, your choices and/or the changes available to you?

I hope you found this Creator’s Roulette conversation with Lee informative and thought provoking. You can find her on her website, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. I will be posting about Imperfect in the coming days. You can check it out on Goodreads.

Cover image: Photo by Brian Garcia on Unsplash

Be First to Comment