I have written a couple of short stories so far in my creative writing career. They don’t come to me often but when they do, there is certain satisfaction that I feel in writing one. Just yesterday, thanks to Layton’s prompt, I worked on a 1440 words long The Boy who Understood Leaves. It took me a couple hours to write and brainstorming with a friend was super helpful. I started writing and absolutely loved the 400 words that came out but didn’t know where I was going to it. Short stories, in my mind, have a point. I did not know my point when I started writing.

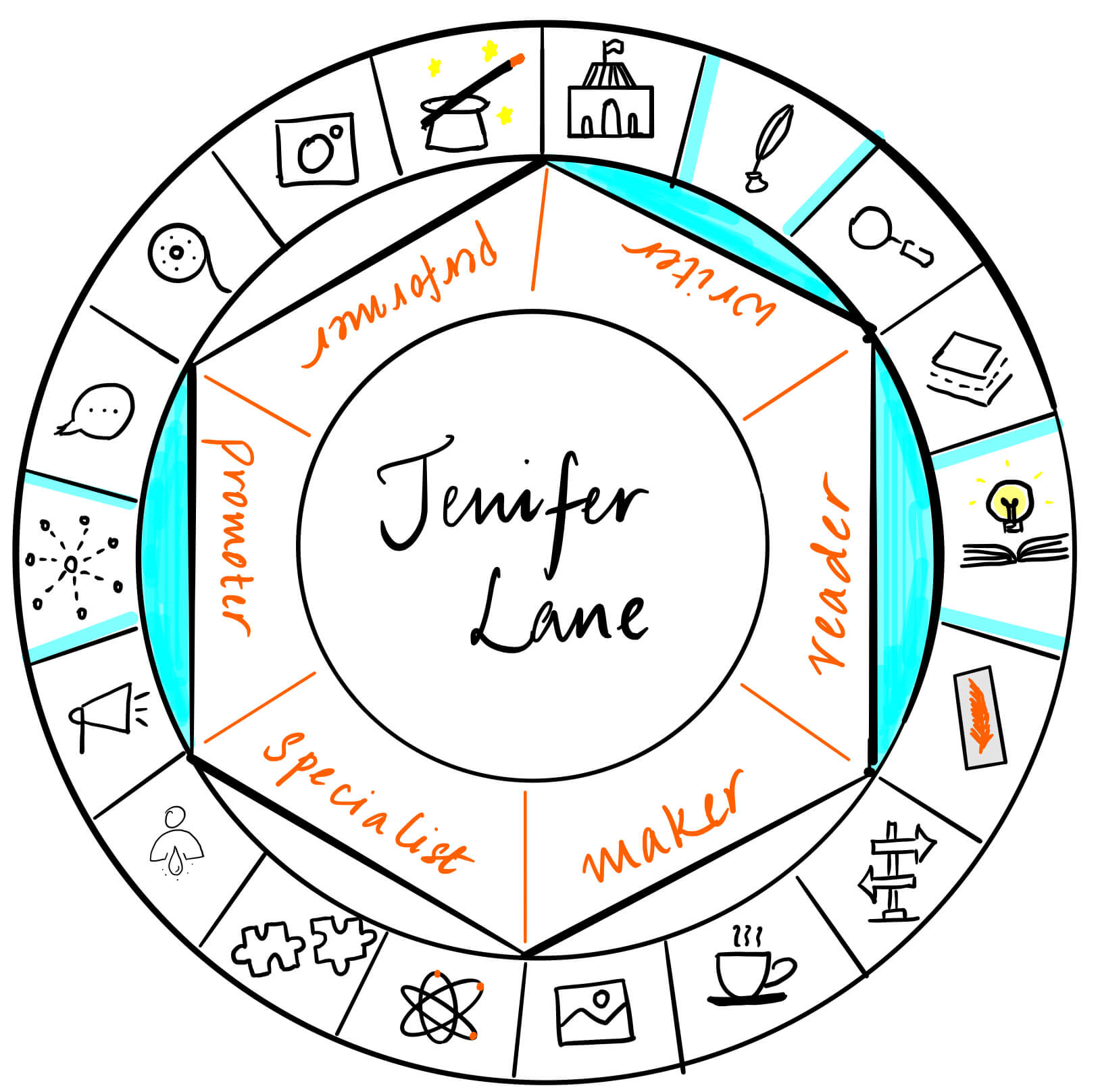

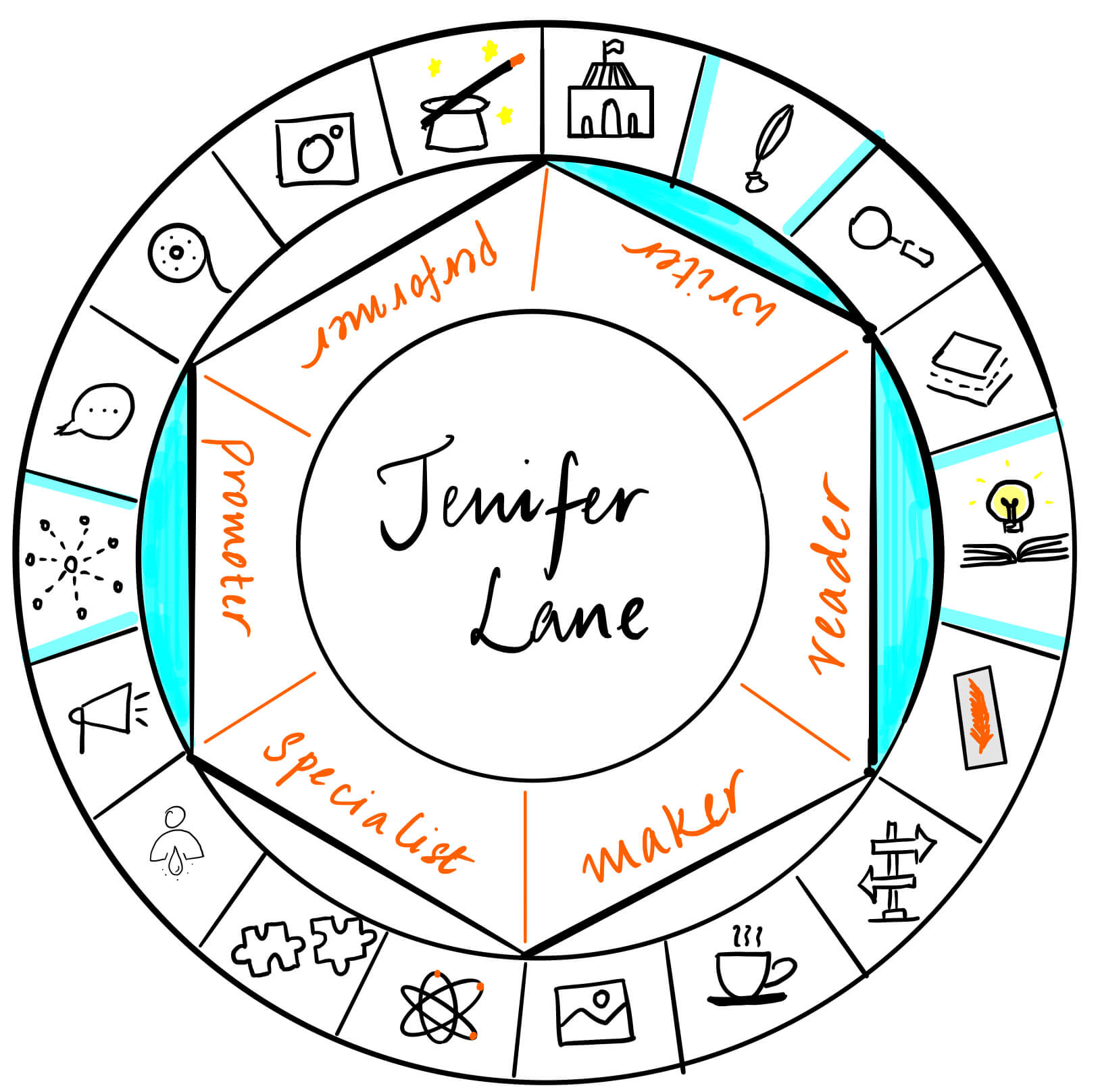

I am excited to have Jennifer Lane today on The Creator’s Roulette to tell us about her experiences with short stories. She is the author of the award-winning novel Of Metal and Earth, of Stick Figures from Rockport, and the Collected Stories of Ramsbolt, including the books Blood and Sand, Penny’s Loft, and Hope for Us Yet. Jennifer shared with me that she uses short stories as a way to keep her readers engaged with her book series. Let’s hear from her!

It was 1992. The world was singing along to Whitney Houston’s I Will Always Love You, and people were wearing their pants backwards thanks to the influence of a new hip hop group. It was before Beanie Babies turned rational adults into fiscally liberal retirement plan investors, and I was fifteen years old, stuck at a desk on a sunny day, staring at a doppled fifth generation photocopy of a short story. It smelled of sour high school copier ink, and some of the words were hard to make out, but that story—about a guy who pukes bunnies—was a particularly good one. And I was psyched to talk about it.

Short stories weren’t a thing in my world. Books, long books, were everywhere.

The house I grew up in had built-in bookshelves full of books my grandmother left when they sold the house to my parents. Hemingway. Shakespeare. I read all of them before I was a teen, lying on a beach blanket in my rural backyard, trying to get some summer sun from beneath a bigleaf maple tree. I absorbed every word, picked apart Shakespeare’s iambic pentameter, and I mourned the ending of every work I read. As an only child with few friends, I found belonging in those worlds. And when they ended, I always wanted more. I would visit my grandmother and we’d talk for hours about King Lear, Juliet, and how the sun also rises.

Books were everything. Short stories were never enough.

And so it was that I sat in a short story class, expecting an easy A, waiting to hear what the cute boy next to me thought of the metaphors in Julio Cortazar’s Letter to A Young Lady in Paris.

How could a writer, without exposition on hair color and skin texture, without deep descriptions of place and the point, possibly present a story so compelling? His age is no matter. His job and life goals all fall to the wayside. There are no flashbacks to emotional power surges that fried his youthful brain, instilling mistrust and a blindness that must be cured in three hundred pages. Instead, it’s one letter. Seven sour splotchy pages.

It was a riveting telling of one man’s struggle to tend to the bunnies he vomits. One man’s self-imposed prison, creating a system to deal with his madness. He thought he’d cracked the code, tending fragile clover to appease his ravenous bunnies. Compassionate disposal of the anxious side effects was a source of his pride. He battled isolation until the bunnies give him away, until the outward manifestation of his turmoil became too much to bear. In seven pages.

What makes this short story work is not the vibrant setting of the apartment he’s looking after. What comes through to the reader is how the immaculate setting intimidates him with its elegance and simplicity. It isn’t the bunnies he spews, but the unease in his prose as he notes their rising frequency, his alarm that the recently retched were not white but black and grey. And it isn’t the ending either. There’s no drawn-out realization, no long dramatic dialog professing the change to his course of life. What makes this short story work is being dropped into tension at the start, thrown into a moment of truth for a character fully developed. This event of tending to someone else’s apartment pushing him to the bring, and we’re ripped from the scene at just the right moment.

As short stories go, it’s more than enough.

There’s no waste. The character’s dilemma is everywhere on the page. It’s in the prose, in the colors he chooses, in the spines of the books his bunnies eviscerate. It’s in the first words. “Andrée, I didn’t even want to come stay in your apartment on Suipacha.” He’s on the brink and the author brings you to it.

As a reader, I love to teeter there.

Short stories are often seen by modern writers as a way to gain some credibility, to gain a few publishing footnotes in author bios slapped on the back of larger works. It’s a craft to hone, a blade to sharpen in a war with the words. Though many have perfected the craft, few indie writers incorporate them into the cannon of their works.

Thinking of short stories as lesser had been a youthful failing on my part. And thinking of them as separate from broader, longer works was a failing for too long as well.

When I started my current book series, The Collected Stories of Ramsbolt, I dove back into the craft of short stories. I hadn’t waded in that pool for more than a decade, but now I’m finding a series of two-prong benefits: one for me, one for the readers.

Inspiration can dry up. Digging into a character’s backstory and diving into a pivotal moment, lets the story flow. I benefit from the creative freedom, and my story writing skills will improve. And then I gift them to my readers.

How? Offer them up for free with a newsletter subscription. Add them to your website as free reads and send them out to your subscribers to keep readers engaged between book releases. Share them with compelling images that represent the world in your writing. Publish polls to your social media feeds to find out which characters your fans want to hear from. Go back to that well again and again. It’s good for you and great for your fans.

It’s been three decades since I sat at that desk in a high school classroom, steeped in ink, short stories brewing. I was excited to talk about a man who puked bunnies. That story moved me. Not everyone felt the same. Some were repulsed. Others found it repugnant. But I was enthralled, enraptured, inspired.

In the last lines of Julio Cortazar’s Letter to A Young Lady in Paris, the main character never signs off. After all that anguish, the planning and cover-up of a life bizarre, denying his tortured reality for so long and purging it onto a page, his letter goes unsigned. His story goes unfinished. I couldn’t wait to point that out. But the bell rang. Class ended. I lost my chance.

Every moment propels life forward. Even tiny ones have the capacity to change a life. Dabbing up coffee spills and sweeping up fodder from cat litter boxes. What makes that story compelling isn’t the length of it. It’s the drama and tension that matter. It’s the character grappling with a changing reality that pushes them into a whole new domain.

A short story is less than. It can mean everything.

Hoping to connect with Jennifer? Find her on:

Website

Photo by Nick Morrison on Unsplash

Be First to Comment