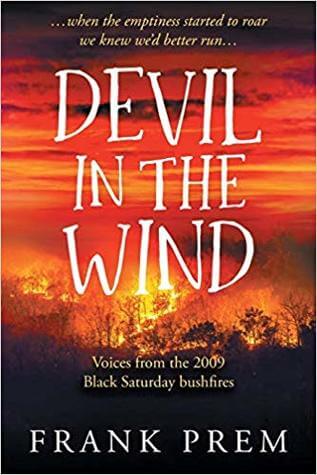

The latest #bookthoughts on the blog have been about Devil in the Wind by Frank Prem. Devil in the Wind represents the voices of the people who lived through the wildfires in Australia in February 2009. Sharing experiences of these people from many ages and occupations, at different times of the catastrophe, Frank’s poems are moving and haunting at the same time.

I’ll be honest since I read that poem collection, I’m in love with poetry. I even attended a book reading yesterday for the latest by poet, Atticus, The Truth about Magic, and got myself an advanced reader copy for Allie Michelle‘s The Rose that Blooms in the Night. Anyway, my poetry adventures aside, let’s talk to Frank about his works and his journey in poems!

- As I have mentioned to you before, poetry expresses the feelings, distribution, loss that came about because of the fires. What made you decide to choose poems as your means to express yourself?

The poems in Devil In The Wind all came about through my own immediate (direct and indirect) experience of the fires.

The fire event itself was quite catastrophic and all consuming for the whole of my State of Victoria (equivalent to a province in other countries and with a population of around 6 million). Everyone was involved, either through being in harms way themselves, or through fighting the various blazes (there were hundreds burning), or being close enough to experience the fear and tension. Anyone not involved in those ways, was held spellbound by the unfolding disaster and destruction as it gradually was revealed on radio, television, newspapers and, later, the commission of enquiry.

Everyone knew of someone, or had family at risk.

I feel that I had little choice with regard to the poems that appear in the collection. They demanded to be written and all are included.

- What was the first poem you ever wrote about? Do you still have it?

The first poem I recall writing was way back in high school. Instead of the scheduled essay for my English class, I wrote a free verse poem on the chosen topic, which was something to do with Autumn.

I no longer have the poem, but I recall it started (written in ballpoint on a lined page) this way:

falling

falling

falling

the leaves . . .

the rest is lost to me, but recalling that beginning, I suspect I haven’t changed my style all that much.

- What was your experience of researching for Devil in the wind? How did you reach out to people to talk to you about this?

My research was all experiential, and took place at the time and in the moments of first encounter.

I wrote what I experienced personally and what was told to me directly. I read the news and listened to the wireless – often in the middle of the night to get the latest updates.

I listened to the radio and to my own fears and distress.

All these things became stories that I couldn’t not hear. Once heard I couldn’t ignore them and felt compelled to write them, as a way securing my own peace of mind.

When I thought I had heard it all, the Royal Commission began and new stories emerged. Again, I couldn’t stop listening and was compelled to write them down as I heard them.

The body of work lay in a drawer, so to speak, for the best part of 10 years until the pending anniversary of the event and my own development towards becoming a published author led me to finally compiling them as a collection in book form and available for others to share.

- What was the most astonishing revelation from the interviews that you had with people for this book?

In a curious way, my interviews have come after the event of publication.

The fires remain a difficult subject here in Victoria. My own belief is that we as a whole are still experiencing a kind of post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD). I have found that raising the subject with a victim or survivor of Black Saturday readily draws tears and distress that is real and unresolved.

After listening to my reading of poems from the collection, however, I’ve found that it seems easier for folk to describe their own experiences, as though they have been vicariously joined by other survivors and after a sharing of those written down stories, there is a catharsis possible.

I would not want to overstate that, but it is my feeling that the poems make the sharing just a little bit easier.

- You have a unique style of writing, without punctuation. What made you adopt this style? Personally, I found that as I read, I was pausing where it felt natural to me, which is different from reading a punctuated script.

Yes, that is a real feature of what my writing has become. In my most current approach I use lines of one, two, and three words a lot.

This approach began when I started reading live (I always read, I don’t recite).

I began turning up at spoken word venues soon after I decided that I was a poet, rather than a dabbler in rhyme or verse. I lived in Melbourne at that time and I started to haunt the spoken word venues of the day looking for my 3 poem/5 minute maximum time allocation behind the microphone.

I assiduously wrote new work for each Saturday reading and found that before each performance I was madly doing my final edits longhand. Punctuation started to get in my road because it failed to assist me in delivery of my lines.

I increasingly found myself pursuing line breaks that supported and directed inflection, nuance, short pauses, long pauses and so on.

For me, poetry was not sentences with line breaks, it was myself communicating an idea or thought or story or song to my listeners.

Over time I have developed this to a point where, in my own mind, I believe that my approach can be helpful in teaching reading aloud, or at least enabling coherent reading on a first exposure to the passage of writing. <Phew!>

That’s a little bit extravagant, perhaps, but I have come to believe that language is a music that is spoken and is a kind of poetry in itself. Punctuation is only a way to formulate sentences.

- What does it mean to a poet?

Over the journey I have trained myself, I think, to experience the world around me and the ideas and thoughts that I think as poetry.

It has become natural to me and much of the work that I post on my daily poetry blog is the capture of a thought, represented in a way that a reader can access it and that might lead that reader to another thought of their own.

I think the thought and express it as a poem that can then be accessed and contemplated by another. Is that not wonderful? That’s what I think a poet is and what poetry is for, though sadly, the necessary emphasis on accessibility for a reader is too often neglected.

- Tell me about New Asylum – your next poetry collection.

My first free-verse memoir was Small Town kid which recounts stories and experiences of a fairly typical childhood in the 1960s and 70s. The New Asylum is the experience of that same Small Town Kid with and within psychiatry.

Psychiatry has always been a controversial area of medicine. Public psychiatry is intricately interwoven with the law and with involuntary treatment, or incarceration. There has always been a Mental Health Act in play.

When I was a young child my parents both worked in a rural Mental Asylum, as places of treatment were then known. I was a regular visitor to their workplaces and later became a student psychiatric nurse myself, before moving on into acute psychiatry and management and finally coming back to work with people experiencing the profoundly disabling effects of a lifelong psychiatric illness.

Like the childhood experience of the 1960s and 70s with its great freedoms for a child, psychiatry has changed, as well. The Asylums are gone. Mental Health Acts come and go. The nature of the clientele and the reasons for requiring treatment change.

We have treatment revolutions that blow in like storms filled with promise (such as community based treatment, new generation medications, protection for legal rights) – but whether of wonderful benefit or disastrous consequence, it can be difficult to tell until hindsight lends its enhanced vision.

Folk will have to make their own judgements about the effects, but the poems will, at least reflect the storms and some of the ways they impact on people.

The poems include sections dealing with all the above areas, childhood experience, nurse training and the wider arena that is public psychiatry.

- Some people take a notebook or notepad with them wherever they go, in case of a sudden flash of inspiration hits them. Are you one of them?

I am indeed.

I have taught myself to think my raw thoughts directly into the computer, but I’m hopeless at typing into a device. Too many fat thumbs.

A notebook and pen are best friends.

- Are there any books that you would say influenced and shaped you as a writer and poet?

As a young reader I found our Australian bush poets such as AB (The Banjo) Patterson and Henry Lawson quite compelling, and I think their work has stood the test of time (they wrote in the 1800s). I believe they achieved lyrical qualities that transcended rhyme and metre in their poetry, and Lawson’s short stories remain iconic exemplars of Australian life and character.

In more recent times I have been enchanted by the work of French philosopher Gaston Bachelard in his discussions and reveries about poetry and poetics. Reading his work inspired a collection in excess of 700 poems exploring my own imagination while pursuing the themes his work had suggested. I fervently hope to put these poems together into a series of collections that ride beneath a banner inscribed ‘surreal’.

- What would you tell your younger self when it comes to writing?

I would tell my younger self and indeed any budding writer to be patient, and to allow all the time necessary to develop their craft.

Writing to a high standard, telling stories to a high standard does not happen overnight. It is a learned craft requiring many iterations, and should not be rushed.

At the same time, I would say that starting early is critical. I have seen too many aspiring writers with a story to tell wait until they retire, or until they have the spare time to pursue their writing.

Sadly, the result is too often frustration because the skills have not been developed.

For writing, the right time is always ‘now’.

It’s been a pleasure connecting with Frank and getting back into enjoying poetry.

** Devil in the Wind is now available so get a copy and let me know what you think! Let’s have a poetry-discussion! **

Amazon Print

Amazon Kindle (available on Kindle Unlimited)

Let me and Frank know what you think! We can be found on Twitter as @frank_prem and @_armedwithabook. Don’t forget to check out my book thoughts here. Thanks for stopping by!

Cover image: Photo by Ricardo Gomez Angel on Unsplash

Thanks you, Kriti. It’s been a pleasure!