Hello, friend! Welcome to a new post in The Creator’s Roulette! In a recent post on the series, Jennifer deBie shared about her love for fairy tales and the feeling of coming back home these stories we grow up with provide. Today I am hosting author Julia L. Robertson and she is going to take another look at fairy tales – it is time to dive into women’s work in fairytales! Julia is the author of Into the Underwood and you have met her when she was on the blog last sharing an excerpt from it. 🙂 Let’s learn from her!

The Heroine’s Journey:

Women’s Work in Fairy Tales

A guest post by J. L. Robertson

The Stories We Tell

Whether writing a screenplay for a Hollywood film or simply talking about our day, the way in which humans have always related to each other and forged our strongest bonds is through the act of storytelling. It is a daily, even hourly exercise, stringing one action to the next, extending from one year to the next, making sense of a lifetime of experiences, which, without the connective tissue of narrative, would be little more than a collection of sensations and stimuli with little cohesive purpose. Stories are what give our lives a sense of coherent meaning, forming the basis of our morality, and offering a sense of identity beyond that of our own relative insignificance to the world.

As such, the stories that we tell about ourselves, our society, and our respective cultures are also those which are held in the highest, and often, most sacred esteem. Of these stories, those that resonate deepest and stand the test of time are often those which are most broadly related to the lived experiences of the largest number of people. After a long history of warfare and military conscription for most fighting-age men, stories like The Iliad and The Odyssey continue to be taught in schools, made into movies, written about in novels, and even issued to grieving soldiers by the US military. Likewise, The Holy Bible, one of the most widely distributed books in the world, relates primarily the stories of herdsmen, slaves, farmers, carpenters, and fishermen: what would have been the most common occupations before our modern era. Through closer examination, one can see that what draws people to such stories is not just the relatability of the characters’ given professions, but the elevation of these mundane occupations to that of heroic and even Divine status. Odysseus is not just a warrior, but one clever enough to outwit the gods, seduce nymphs, and drive invading suitors away from his home. Moses was not just the son of a Hebrew slave, but a prophet and leader who crippled a powerful nation with a shepherd’s staff and rescued his people from bondage. Jesus was not just a carpenter, but a miraculous healer who communed directly with God and even overcame death when it came for him. Is any wonder that such stories, in their elevation of the most ordinary human experiences to such lofty heights, would still be so well-regarded today?

It is much the same when it comes to the stories of women. After all, Odysseus is not the only clever one in his story, but his wife, Penelope, his equal in both wit and resourcefulness, guards his household for over twenty years by weaving and unraveling a funeral shroud to hold her husband’s contenders at bay. So too is the ordinary act of conceiving and bearing children elevated to the level of Divine communion within the personage of Jesus’ mother, Mary. The song of Moses’ sister Miriam, sang in celebration at the vanquishing of the Egyptians, is one that is read at every Jewish Passover service and Catholic Easter Vigil mass. However, even in all these examples, the stories are told by men, with a man as the focal point of the narrative, with women acting only as a cast of supporting characters. Their roles in both the stories and the telling of them act only as a reflection of their social role throughout much of history: voiceless, ancillary, important on occasions, but only in relation to the male protagonist. However, a closer look at the other side of the mythological landscape reveals that there are certain exceptions to that rule.

Fairy Tales and Their Tellers

Fairy tales and folk tales, as one might expect, are most often attributed to the men who collected and complied them. The Brothers Grimm, Charles Perrault, Hans Christian Anderson, and Oscar Wilde are all household names credited with giving the world such classics as Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, Cinderella, Thumbelina, Beauty and the Beast, and The Little Mermaid. However, despite the masculine names slapped on the covers, further research finds that the material for these stories was drawn from an altogether more feminine source. The relating of these tales to the aforementioned folklorists often came via mothers, sisters, nurses, wives, grandmothers, and other anonymous, low-status women. In her book, From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers, English historian and mythographer Marina Warner writes of the Grimm Brother Wilhelm that he “married Dortchen, the youngest of four daughters of Dorothea Wild, who possessed a rich store of traditional tales, and she provided thirty-six for the collections. Dorothea, the Grimms’ sister, married Ludwig Hassenpflug, and his three sisters passed on forty-one of the tales” (page 20). Of Oscar Wilde, she wrote that his father, “a doctor in Merrion Square, Dublin, in the mid-nineteenth century, used to ask for stories as his fee from his poorer patients: his wife Speranza Wilde then collected them. Many of these were told to him by women, and in turn influenced their son’s innovatory fairy tales, like ‘The Selfish Giant’ and ‘The Happy Prince.’” (page 20). These stories, as one might expect, were often told while their tellers were engaged in common female occupations, like spinning, weaving, sewing, and other household chores, and the language we use around narrative has come to reflect that. “Spinning a tale, weaving a plot: the metaphors illuminate the relation; while the structure of fairy stories, with their repetitions, reprises, elaboration and minutiae, replicates the thread and fabric of one of women’s principal labours—the making of textiles from the wool or the flax to the finished bolt of cloth.” (Page 23). And just as with the aforementioned male examples, through the medium of fairy tales, these domestic handicrafts and their makers are elevated to heroic levels.

The Six Swans

One popular example includes the Grimm Brothers’ tale, “The Six Swans,” in which an old king with six sons and a daughter, marries an evil sorceress. Hoping to rid herself of her stepsons, she uses her magic to turn them into swans, a spell that can only be broken if their sister spins, weaves, and sews six magical shirts out of stinging nettles and maintains a vow of silence throughout. The sister vows to fulfill this task, and over the course of six years, sews the shirts and maintains her muteness, even when she is falsely accused of a crime and sentenced to be burned at the stake. In the end, she saves her brothers in the nick of time and reclaims her voice, which she uses to expose her accusers.

Bluebeard

Another example is that of Bluebeard’s wife. Attributed to Charles Perrault, the story tells of a naïve young woman married to a wealthy, blue-bearded nobleman who had several wives before her. As was customary at the time, she becomes “the mistress of the keys” and is told by her new husband that she is welcome to open any room in the castle except one. After he goes away, the young bride invites her sisters over, and together they begin opening the doors to all the rooms, all of which are full of dazzling riches. At her sisters’ behest, she opens the door to the forbidden room and there finds the murdered corpses of her husband’s former wives hanging from hooks on the wall. In her horror, she drops the key into a pool of blood and is unable to wash it off. When her husband returns, he asks for the keys he had given her, and upon seeing the bloodstains, discovers that she has been in the forbidden room. He flies into a rage and threatens to kill her on the spot, but she begs for a few hours to pray before she is dispatched. He agrees to her request, and while she is “praying,” she sends her sisters out to fetch her brothers. Just as her time is up and Bluebeard is about to end her life, her brother’s arrive and kill him before her can. The wife inherits her husband’s estate and divides its wealth among the siblings who came to her aid.

Vasilisa the Brave

Lastly, in the Slavic fairy tale “Vasilisa the Brave,” a dying mother gives her daughter a magical doll, instructing her to keep it with her always. After her death, Vasilisa’s father seeks out a new wife to act as a mother to his daughter and chooses a widow with a daughter of her own. The stepmother, however—as is so often the case in fairy tales—is very cruel to Vasilisa and makes her do all the household chores while her own lazy daughter does nothing. One day, while the father is out of town, the stepmother sends Vasilisa into the woods to fetch fire from the child-eating witch Baba Yaga, knowing that her stepdaughter will likely die in the undertaking. Vasilisa wanders the woods until she finds a house standing on chicken legs, surrounded on all sides by skulls with glowing eyes, and upon her arrival, is greeted by Baba Yaga who flies in on a magical mortar and pestle. Baba Yaga assigns her a series of domestic tasks: washing her laundry, separating grains, cooking her meal, all of which Vasilisa completes in impossible time with the help of her magical doll. Impressed by her industrious work, the witch gives Vasilisa one of the glowing skulls which contains the fire she had been sent to retrieve. Vasilisa carries the skull home, and upon her arrival, shoots fire out of it, burning her stepmother and stepsister to ashes. She later goes on to become a skillful weaver and catches the attention of Tsar, who makes her his wife.

Modern Fairy Tales and Their Tellers

In all three examples, it seems obvious that their original tellers would be women, reflecting very clearly what would have been the principal duties, concerns, anxieties, and ambitions of your average woman during the time in which they were recorded. However, even today, many female writers are continuing this tradition through the creation and retelling of fairy tales of their own.

In 1979, UK writer Angela Carter started the trend by publishing her most iconic work, The Bloody Chamber, a collection of provocative fairy tale retellings featuring strong, and often ferocious, heroines. In its title story, set during the early 20th century, a young pianist seeks to escape poverty by marring a wealthy French Marquis in defiance of her mother, who had foolishly married for love. In the end, it is her mother’s love that saves her when her husband’s perverse and bloodthirsty tendencies are exposed.

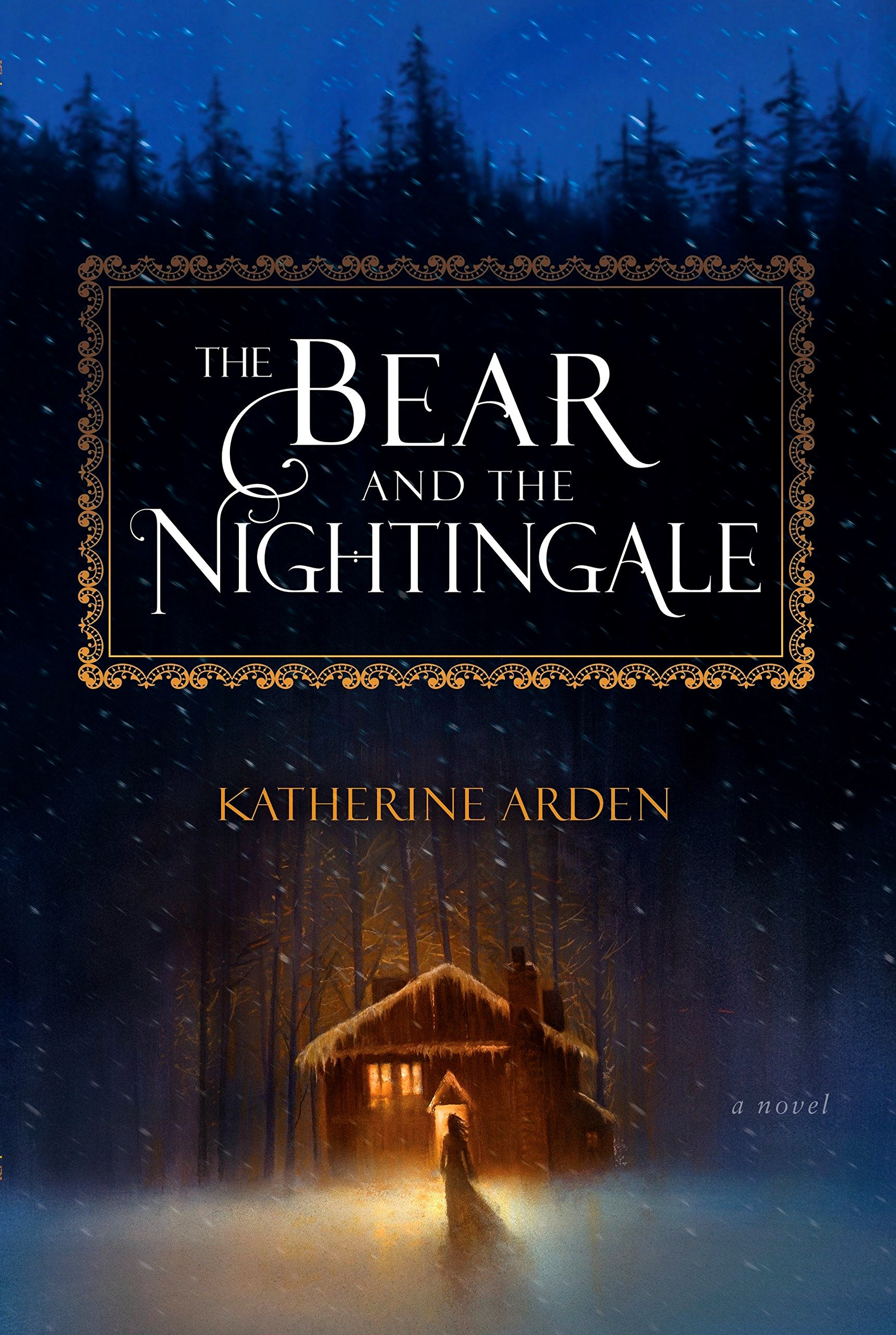

In Katherine Arden’s Winternight Trilogy, Vasilisa the Brave is reimagined as a boyar’s daughter in Medieval Russia, fraternizing with nature spirits and rebelling against the suffocating religious and sexual strictures of the surrounding, patriarchal culture.

Likewise, in the novel, Six Crimson Cranes by Elizabeth Lim, “The Six Swans” is recast against an Asian-inspired fantasy landscape, drawing source material from both Eastern and Western folkloric traditions and weaving them together into a young girl’s heroic quest to save her kingdom.

Though the original tellers of these tales might have been nameless, their credit going only to the men who collected and published them, women today are taking their voices back, reclaiming what can be rightfully called our legacy and embarking time and again upon a Heroine’s Journey of our own.

Have you read the tales Julia has analyzed above?

Had you thought of them from this aspect before?

Thank you for hanging out with us today. You can connect with Julia on Facebook, Instagram and learn more about her latest books on her website. You can also follow her Amazon and Goodreads pages for updates.

Cover Image by Kriti

Thank you so much for this post, Kriti!