Welcome friend. As part of the Canadian Indigenous History Month in June, I read Valley of the Birdtail: An Indian Reserve, a White Town, and the Road to Reconciliation. The centre of this book is a reserve and a town not far from it. With historical details and current accounts, Valley of the Birdtail is an innovative narrative about history and how it is interwoven into present day events and challenges. It was a hard read for me and I absolutely adored it.

Valley of the Birdtail: An Indian Reserve, a White Town, and the Road to Reconciliation

By Andrew Stobo Sniderman, Douglas Sanderson | Goodreads

A heart-rending true story about racism and reconciliation

Divided by a beautiful valley and 150 years of racism, the town of Rossburn and the Waywayseecappo Indian reserve have been neighbours nearly as long as Canada has been a country. Their story reflects much of what has gone wrong in relations between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous Canadians. It also offers, in the end, an uncommon measure of hope.

Valley of the Birdtail is about how two communities became separate and unequal–and what it means for the rest of us. In Rossburn, once settled by Ukrainian immigrants who fled poverty and persecution, family income is near the national average and more than a third of adults have graduated from university. In Waywayseecappo, the average family lives below the national poverty line and less than a third of adults have graduated from high school, with many haunted by their time in residential schools.

This book follows multiple generations of two families, one white and one Indigenous, and weaves their lives into the larger story of Canada. It is a story of villains and heroes, irony and idealism, racism and reconciliation. Valley of the Birdtail has the ambition to change the way we think about our past and show a path to a better future.

My lenses on Valley of the Birdtail

I came into Valley of the Birdtail with more perspectives than I had even imagined. As I read about the Waywayseecappo Indian reserve and the town of Rossburn, the broader Canadian history that played a huge role in the shaping of these two communities and their relationships, so many aspects of my life experiences and identities came up.

As a student

Maureen Twovoice is one of the central people in this book. Her early education was in a city but when she moved to her family home in the Waywayseecappo Indian reserve, she found the level of her studies there highly uninteresting. The material was things she had already learned and because she did not feel challenged enough, she started to ignore school. This is the first time I learned about the differences between the standards that students are held to and taught at the reserve as compared to a town. There are many reasons for this that Valley of the Birdtail goes into in depth, especially when Tory Luhowy, a teacher from Rossburn, shares his experiences of teaching at reserves.

I deeply connected with Maureen’s need to be successful and engage in her learning. I was rooting for her to make her dreams come true. The importance of education had been drilled into her by her elders, who did not finish school themselves but saw it as a way of leading a better life. I was glad to hear that Maureen, and many other people mentioned in this book, were eventually able to succeed in getting the education they wanted.

As a teacher

As teachers, we meet a wide variety of students from many backgrounds, socio-economic status, families and much more. It is always fascinating to me how we can build deep connections with a student under our care – once we get to know them, see their potential, hardships, challenges, it is not possible for us to step back and let things go. We want to encourage them, show them what we see in them and do all we can for them to be successful.

Tory Luhowy and his father’s experiences teaching at the reserves, young and older students, was heartwarming to read about and showed how being with people we may think are different from us changes our minds. When we are with an individual, we interact with them as one. Hopefully, the layers of stereotypes, misconceptions and illwills can be resolved when we open channels of communication and are able to listen.

Recognizing that the reserve was not getting the same funding per student as the town of Rossburn, a team of individuals, including teachers, government officials, put together a proposal to see how things would change if the funding was indeed matched. Valley of the Birdtail goes into details around how this disparity came to be, how it affected the students on the reserve as well as the students who had to come to town for high school because the reserve did not have one. A partnership happens when both sides see something to be gained and through the efforts of the schools, the Waywayseecappo Indian reserve and the town of Rossburn, I believe that the way forward for us is to make changes at the smallest level – education is a powerful place to start. If we can train our young generations to look past the prejudice they have grown up with, we can give them the power to change the narrative and build the lives they want.

As someone from a colony

Valley of the Birdtail presents the history of Canada from the time the treaties came into effect. Through historical records, diligent research and open discussion, the authors present how the country wide policies around immigration and indigenous rights affected the Waywayseecappo Indian reserve and Rossburn.

I loved the generational aspect of this book as the historical events were tied to personal familial histories of Maureen Twovoice and Tory Luhowy. In Troy’s case this related to when his family moved to Canada from Ukraine and how the sentiments of the town evolved towards Ukrainians.

For Maureen’s family, it was about tracing back to how they came to settle in Waywayseecappo, who went to residential schools and how that affected their role in the community. Maureen’s grandfather attended these schools and placed a huge emphasis on education. Her mother lost her hearing the first week of being at a residential school. Maureen, who is likely in her 30s by the end of the book, is the first generation in her family to not have gone to a residential school. I could see how generational trauma manifests in bringing up children and how much the indigenous people value education, within their own culture, but also what the settlers teach.

I think about how people born around the same time can have vastly different upbringing and experiences.

I grew up in India. My parents were born 20 years after India got its independence from the British. My maternal grandparents were young when the partition took place and they migrated into India with their families.

Canada is a different story. It was a place where people were encouraged to move from Europe but considering how cold it gets in the north, the government implemented many tactics to entice people to come. It failed towards the indigenous people whose lands it took. It restricted them to small areas and did not give them the support they needed to keep up with technology and advance at the same pace as the settlers. The last residential school closed in the late 1990s in Alberta. That was not very long ago. Canada may have been free of British rule since the confederation but the constitution and laws developed by the British and settlers are still around.

As I read Valley of the Birdtail, I wondered about my own history. School teaches facts but the reality is in people’s experiences and this book adds the historical context to real people’s lives in such an impactful way!

It encouraged me to research perspectives on India as a colony. I marvelled at the grasp that English has on india. In Grade 9, I could opt out of Hindi, my mother tongue, but not English. There are opinion pieces online about how being colonized by the British was good for Inda – how we were these independent kingdoms that the British brought together into a country. I don’t know what the alternate history would have been but the common point that colonization shares across the globe is that the people of one country thought they knew better than others how to live, that their way of life, religion, technological advances, languages, etc. was superior. Babel by R.F. Kuang (Goodreads) brought this up beautifully and I am grateful that both fiction and non-fiction freely question the tenets of colonisation now.

As an immigrant

I moved to Canada in August 2014. I joined a computing science program at a public university and for two years I was oblivious to even the existence of indigenous people. In 2016, I moved into Education and that’s when the treaty acknowledgements were suddenly everywhere. I thought it was to do with being in the arts but it was actually the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada that, from 2005-2015, “provided those directly or indirectly affected by the legacy of the Indian Residential Schools system with an opportunity to share their stories and experiences”. To me, the Treaty acknowledgement meant very little. I was an outsider who had no context. My family moved to Canada in the last twenty years, I did not know what something from so many years ago had to do with me. But that’s what I thought – that it was from so many years ago. But was it really?

During my teaching degree, I took a mandatory course in Indigenous history. It was Fall of 2017 when I finally got a thorough historical background and I started to understand what this meant as a teacher and someone wanting to call Canada home. I adored that course. I grew so much. And it was just the beginning. You can read one of the reflections from this course in my recent review of Helen Knott’s Becoming a Matriarch.

As someone who calls Canada home

I originally thought I would write as a ‘new Canadian’ but that is still a few years away legally and as someone who has often felt excluded by the official terms, I will speak more broadly here.

Canada is my home. It is also the home of many international students I started my university education with, all of us at various stages of residency. We came in knowing nothing and hopefully, as we embrace this country for inviting us to be here, we also take the time to understand its history and support it in the challenges its peoples face today.

Growth in knowledge is not limited to someone like me though. I ask my friends and family what they learned in school about Canadian history, indigenous history is particular, and it seems fairly recent that residential schools and the sixty scoops are taught about in school. The history of Ukrainian people, how and when they came to Canada is new to many who were born and raised here.

This place is my home and this is where my children will grow up. So I take it upon myself to learn the history. I am not on the front lines, I am not a teacher but I am here and I will have a say in my kids’ upbringing and in my family. Valley of the Birdtail is a beautiful book to get started. It has a hopeful message with some ideas on what we can do at an individual level to move things forward.

As a human

We may live in a country, province, community, family, and may have multiple identities as immigrants, teacher, student, veteran, first generation, college graduate but ultimately, we live our own life.

What we need is conversation. A safe place and people with whom we can be vulnerable and talk about how history, stereotypes, depiction in media, our families and upbringing affect us. We can then move beyond what we think the societal/political right thing is and figure out how as an individual, we can make a difference. The partnership between Waywayseecappo Indian reserve and Rossburn is exactly this. Where individuals saw something, discussed the idea with other people and decided to get together and make things better for the kids. They are the future and it is fascinating the lengths to which we will go for them.

If you call Canada home, whether you were born here or not it doesn’t matter, if you can make time for one book, read this one. Think about it. Notice how it affects you. Discuss it with at least one person. Reach out to me if you want to discuss it with me. I am always available.

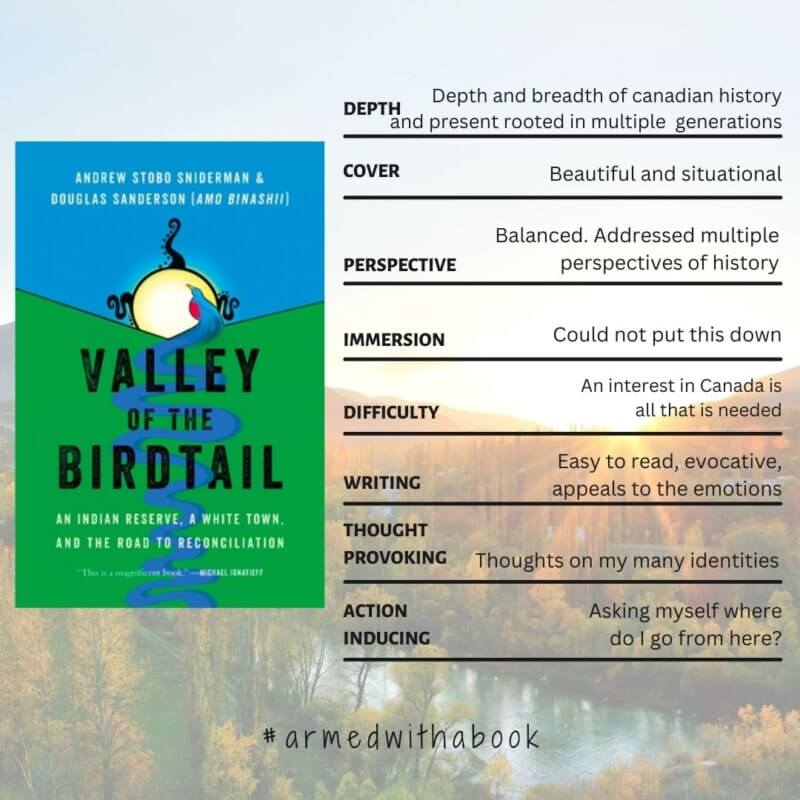

The beautiful cover of Valley of the Birdtail was created by Karen McBride. She is the author of Crow Winter (review, interview). I connected with Karen about her work:

It was such an honour to create the cover illustration for Valley of the Birdtail. The cover is a representation of the river’s creation story done in the Eastern Woodland style popularized by the incomparable Norval Morriseau. I chose to go with a sunrise as the backdrop for the bird to represent the hope that is woven into the story while also giving a nod to one of the characters whose name means “Shining Sun.” Working with Douglas and Andrew and the team at HarperCollins was such a wonderful experience that I would love to do again someday.

Karen McBride

Thanks for reading! 🙂 Find Valley of the Birdtail on Goodreads.

Be First to Comment