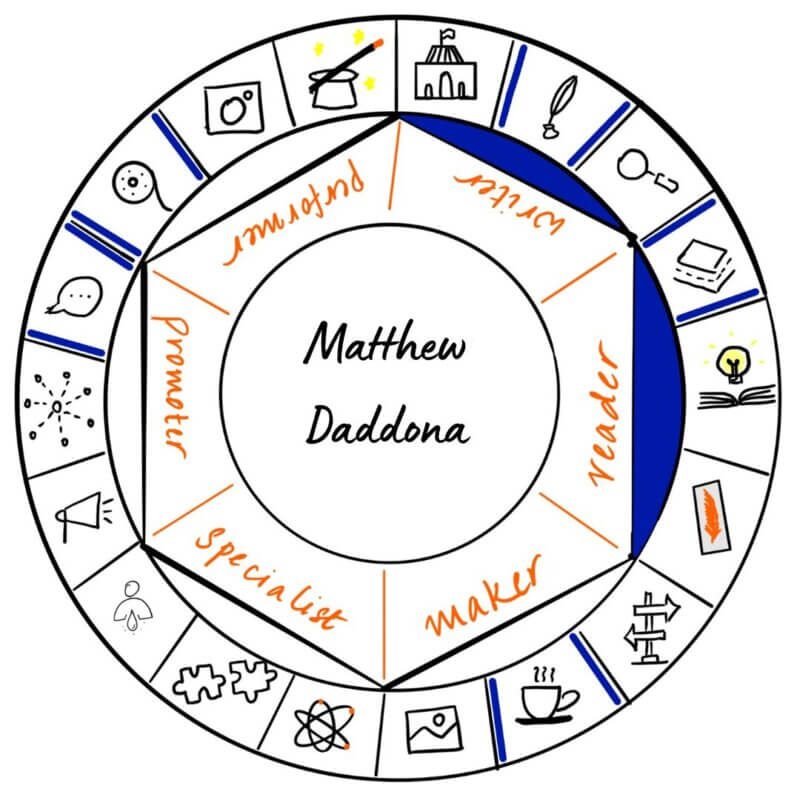

Welcome, friend! I love books but I also love publishing and getting insights into the working on this industry that fuels my hobby is one my favorite things to do. Today, I am excited to bring you an interview with Matthew Daddona, an acquisition editor – turned – writer.

Matthew is the author of the poetry collection House of Sound, which Publishers Weekly called “ruminative…a glimpse into a mind on the search for answers.” A multi hyphenate writer, his work has appeared in dozens of publications, including The New York Times, Newsday, Electric Literature, Whalebone, Tin House, and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. A former senior editor of nonfiction at HarperCollins, he now lives on the North Fork of Long Island, where, in addition to writing, he shucks oysters, installs irrigation systems, and volunteers as a firefighter. The Longitude of Grief is his first novel.

Let’s welcome him and learn more.

Hi Matthew! It is wonderful to host you on Armed with A Book. Please tell me and my readers about yourself.

Hi, Kriti! Thanks for asking me about myself. I don’t think one can mess up a description about oneself, but one never knows. Here goes: I’m a ghostwriter, novelist, and poet, and I occasionally dabble in journalism too. I write all the things, except the ones I don’t want to write, which is a little bit like being an ice cream afficionado until, one day, you switch over to Italian ices. However the mood strikes, I write it. I’m also a volunteer firefighter and a son and an older brother. Oh, and an uncle. I take immense joy in those titles, perhaps over writing. Writing is a thing I do, not something I am. Though maybe the distinction is like the one between ice cream and Italian ices. Sometimes I’m Matthew and sometimes I’m Matthew (the writer), and other times I’m Matthew (the volunteer firefighter) but I’m always Matthew (the human).

Can you share your journey from being an acquisition editor to becoming an author? What inspired you to make the transition from acquiring manuscripts to writing your own?

I’ve always been writing. I’m not sure if that made me a better or worse editor, but I think it was the former. Being a writer has allowed me to empathize with the one trait that’s endemic to writers anywhere, which is rejection. Lots and lots of it. Past, present, and even future rejection, like the kind Liz Gilbert talks about. Truth be told, eventually I got tired of working in corporate publishing and decided I could make more money (and be happier) helping authors directly write their manuscripts, which would also potentially free me up to write my own. I was wrong about that last point: I think I have less time now. But the free time I do have is better spent and enjoyed.

I want to get details about both your acquisition editing experience and your author journey. Let’s start with the book. 🙂 You released your first book, The Longitude of Grief, in May. Tell me what it is about.

The Longitude of Grief is a coming-of-age story about a boy who tries to untangle and understand the complicated, fractious relationships in his life in a small town (kind of like the small town I grew up in). In the first and second parts of the novel, the third-person narrative toggles between two generations—that is the main character, Henry, and his relations in the present; and his mother and father in the past—to explore the inherited parallel of guilt and trauma that comprises family. In the third and final part, the narrative flashes five years later and catches up to Henry’s first-person perspective where he has befriended a senile elderly man, Josef, whose sagacious knowledge about the town and Henry’s plight widens his focus of what’s possible in life: Henry grows closer to Josef but wonder if he’ll be able to glean newfound hope or if Josef is yet another member in a constellation of malevolent men with which he’s surrounded. Kirkus Reviews called it an exploration of toxic masculinity, and though I didn’t attempt to write a book like that, maybe I did. I think they’re right, but it’s also about love. Because every single story is a love story.

What inspired you to write this book?

I’d become obsessed with small towns and the rumour mills they comprise. Beyond that, I wanted to see if I could pull off a novel that balanced many, many characters over a half-generation’s period and do so with a multitude of narrative voices. Judging by the rejections I received, I think I half-pulled it off. I’d rather get rejected for trying than to write something easy and untrue.

How long did it take you to write this book, from the first idea to the last edit?

I started when I was 26 and finished the last edit at 34. Oh Jesus, is that true?

What makes your story unique?

I am hoping somebody else can tell me that. Maybe that there’s a scene where Henry talks about a surfeit of singers with the first name John. Or that he and the elderly man watch porn together. Or that there’s an ‘egging.’ Literally, a house-egging. I really don’t know.

Did you bring any of your experiences into this book?

Lots (see above). No, I’m joking. But every writer brings their own obsessions into a story—mine is the obsession of storytelling, with how stories bend, cavort, and mislead.

What aspects of the publishing process did you find most challenging or rewarding as an author?

The idea that even when the book is done, talking about the book isn’t. Sometimes I wished I could leave it behind and move on to the next work, but art has a way of reminding you of what you’ve done. It’s sweet, really.

Turning to your acquisition editor work, for those of us who don’t know, what does an acquisition editor do? (please skip if you think you already covered it above)

Well, when I was an acquisition editor for nonfiction books, it was my job to receive submissions from literary agents, read them, discuss them with my editorial director and other members of my imprint, and hopefully acquire them if all the stars aligned. I’d received hundreds of submissions every year and would only acquire ten or so books. Those are abominable odds for writers, right? But that’s the world where editors thrive, and writers try to survive. That’s why every writer I had the privilege of working with was so special. They were one of a small, select few. Working with writers was a collaborative process that required a lot of reading, note-giving, conversing, structural-and-line editing, revising, and apologizing. I’d apologize for giving them so many notes and they’d apologize for making me give them so many notes, and we’d come to the agreement that a work is always made better by a desire for both parties to occasionally be wrong.

In your experience as an acquisition editor, what qualities or elements did you look for in manuscripts that you believe contribute to a successful book?

Some editors call it a ‘wow factor.’ Others call it the ‘ability to be proven right.’ That’s because editors are always looking to say no to something (see the statistics above). But I called it the bogeyman, something that haunts you and you can’t get out of your mind. Something that lurks inside your closet or, more applicably, on your nightstand. You turn on the light to shoo it away…or visit it again.

How has your experience as an acquisition editor influenced your approach to writing and the publishing process for your own book?

It hasn’t, if I’m being honest. I wrote a slow, character-driven, and ‘quiet’ novel that many editors or agents called ‘beautiful’ but ‘not hook-y enough.’ Or variations on that. I think I’m okay with not being hook-y enough. Most of life isn’t hook-y. It’s philosophically and spiritually draining. It’s occasionally exquisite. It’s challenging.

How did your background in the publishing industry influence your decision-making process as an author, in terms of marketing, promotion, and building an audience for your book?

I still don’t know what an audience is or how to build one. Can you help me?

What advice would you offer to aspiring authors looking to get traditionally published?

Some famous writer—I think it was Amy Hempel—said something about writing stories that shock yourself. I think that’s correct: you have to surprise, shock, upend, and confuse yourself before you even consider an audience or the “marketplace.” I hate that word. Marketplace. It implies you should be creating something for sale, which, I guess in the real world, we all do. But I like to think about creating work to give away for free but that no one wants. That’s where real art happens.

What is something that a reader of books would not know about the publishing industry?

That it’s obsessed with trends, although maybe that is well known? Okay, how about this? That most junior editors can’t afford to pay their bills while most decisions are made by high-paying executives? That isn’t a publishing problem; it’s a capitalism problem.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

Just thank you. Thank you for taking the time to encourage a love for reading and learning.

Thank you so much for taking the time to chat with me. 🙂

Thank you for reading this post! Do you have any questions for Matthew? Connect with him through his website and Instagram. Check out his book, The Longitude of Grief on Goodreads.

Be First to Comment