Hello friend! November is the month for NaNoWriMo, National Novel Writing Month. You may recall, we started this month with a guest post by author Lucy McLaren where she shared her experience writing a book while taking part in this challenge. Today, I have author Karen A. Wyle with me to share what to do after NaNoWriMo. Let’s get right into it.

What to do after NaNoWriMo

A guest post by Karen A. Wyle

What NaNoWriMo Is For and Who Can Benefit

When people want to start a novel but don’t, or when they start and give up after a few days or weeks, or when they’ve been working on a novel for years and haven’t come close to finishing it, the problem is often the same. They’re second-guessing themselves, letting their inner editor waylay them and bully them. If they’ve started writing, they obsess on everything that’s wrong or incomplete about what they’ve written. If they haven’t started, they’re intimidated by all the obstacles awaiting them.

For people with any of these problems, National Novel Writing Month (aka NaNoWriMo or NaNo) can be a godsend.

NaNoWriMo challenges its participants to write the rough draft of a novel, at least 50,000 words long, entirely within the month of November. One can plan ahead – outline, research, make character and scene notes – or just dive in on the first day. (One can also do NaNo with a different goal, such as a shorter novel or a collection of poems or stories. I’m describing the original idea, what one could call “classic NaNo.”) Writing 50,000 words in thirty days requires writing an average of 1,667 words per day. That’s a pretty good clip, and it doesn’t leave you much time for rereading what you wrote, editing what you wrote, rethinking what you wrote . . . which is the beauty of it.

The website has various forums in which you can bemoan difficulties, ask for help with particular problems, find writing prompts to jolt your imagination out of a rut, or pick the brains of experts in a wide range of scientific or technical areas or historical periods. You can update your word count as often as you like. Particular milestones in word count will be recognized with “badges,” and there are also badges you can award yourself for achievements not registered on the site. If your word count update during the final few days is 50,000 words or more, you’ll be acclaimed a “winner” and have access to a certificate and banner, list of winner “goodies,” and a congratulatory video, created anew for each year’s NaNo. (You may have to go into the list of your badges or messages – I forget which – to find the video.) No matter how often I “win,” I choke up when I watch that video.

What To Do Next

So it’s December 1st, and no matter how much you ended up writing, you have some new words of fiction you didn’t have before. If you “won” NaNo, you have 50,000 words or more. Now what?

Unless you write remarkably clean copy even when writing quickly, you’ll need to work on that rough draft – at least if you want to show it to anyone at any point, or even read it again without wincing. If your ultimate aim is to publish the book (self-publishing) or to persuade someone else to publish it (traditional aka legacy publishing), it’s likely to need more than a little attention first. How to go about that task – how to revise a draft, how many revision passes it’ll take, whether to hire an editor and if so what kind of editor – is beyond the scope of this post. Nor would I prescribe any particular approach as The One And Only Way.

I do, however, have one suggestion. Once you, or you and an editor, have done as much to the book as you can, and it’s as close to final as you can get it, send it to a few beta readers. Beta readers aren’t editors, nor are they involved in the publishing end of things. They’re people who like to read, appreciate the genre in which you’re writing, and are willing to give you some comments. You can even give them a list of questions to answer in addition to sharing whatever other comments they have. (I’d recommend making clear that they don’t have to answer every one of those questions.) If two or more beta readers flag the same problem, you should seriously consider addressing it, though not necessarily adopting any suggestions they volunteer for how to do so.

What to Avoid

Immediate editing: Yes, you’ve kept your inner editor locked in a closet for a whole month, but keep it there a while longer. It’s usually best to put the draft aside for a while — a couple of weeks or a month — at the end of November. Then you can read it with fresh eyes before starting work on it.

Submitting too soon: It can be tempting to give the draft a quick polish and then submit it to an agent or publisher, or enter it in a contest. I advise resisting that temptation. Most, though not all, rough drafts that emerge from NaNo deserve the adjective “rough.” My own post-NaNo drafts often have some or all of the following issues:

- Internal inconsistencies (which I also, borrowing from the world of cinema, call continuity errors). These can be as trivial as a character’s eye color changing between chapters, or as fundamental as characters dying in one scene and then casually strolling into another, with no one taking any notice.

- Repetitions. That particularly evocative and well-chosen phrase? You may have chosen it more than once. (One also needs to watch out for this in revising the draft. That great idea on a line to add may already be there two paragraphs later.)

- Meandering plot and/or unnecessary scenes. This may be particularly likely to afflict pantsers (writers who write “by the seat of their pants” rather than plotting out the story ahead of time). When I’m quickly thinking up scenes and dropping them into my draft, they aren’t always securely hooked onto a good narrative structure. When you love some element of a scene, but it slows the narrative down or just doesn’t contribute to it, it may be time either to delete it (saving a copy for future use) or to find a way to tie it to the plot. (At least, try to use it to add depth to one or more characters.)

Over-editing: There is indeed such a thing as too much editing. (This may be especially true if you’re letting someone else, e.g. a professional editor, tell you how to reword many of your sentences, and if those changes aren’t purely grammatical – or are correcting the grammar of a character who wouldn’t necessarily speak correctly.) One can edit to the point that one drains the authorial “voice” out of the book. It can be difficult to strike the balance between not enough editing and too much – which is one of several good reasons to save previous drafts. If you realize that your latest version is somehow stilted or lifeless, go back to a previous draft and see what passages you want to restore.

Scams: If you decide to self-publish your novel (or if you’ve tried to interest agents and/or publishers and are tired of trying), you need to be on the lookout for scams. These may be sketchy “publishers” or companies promising to help you publish your own book. They proliferate like fruit flies, and can even be affiliated with (though distinct from) major publishing houses.

The worthless publishers, sometimes called (by others, not their own promotions) vanity presses, make their money not by publishing marketable, good quality books but by selling worthless and/or overpriced services to authors. Here are some red flags to watch out for.

- Cold calls: the company calls you, rather than responding to a query from you.

- Extravagant promises: they’re going to make your book a bestseller and you a famous author.

- Upselling: they initially offer a limited, reasonably priced set of services, and then start pushing you to pay for more and more.

If you’re considering a purported publisher, you should check them out thoroughly. What other authors do they work with? What books have they published? Look those books up on Amazon or some other retailer and see whether (if the books show up at all) they look professionally produced and are priced competitively with other similar books. (If you meet someone at a table in the back of a restaurant or in a mall corridor, trying to sell a book for substantially more than a similar book would cost in a bookstore, that’s likely to be an author who fell for a vanity press.)

I strongly recommend looking up any publisher who raises any one of these red flags, or fails the retailer test, on the Writer Beware website. This is run by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association (SFWA), but is not in any way limited to the SFF genre. You can use their search bar and read their post archives. This site has terrific posts about various scams, not only vanity presses.

I’m somewhat reluctant to mention this, but not even NaNoWriMo’s list of sponsors has always been free from scams. There was quite a flap in 2022 when members of the NaNo community started pointing out that one of the prizes available to “winners” came from a vanity press. (I don’t recall whether it was a discount on its services or some other alleged benefit.) As the forum discussion groups grew heated, another sponsor inexplicably outed itself as another such press. The leadership has promised to be more careful in vetting sponsors, but I would still advise double-checking such offers.

Links to Check Out Re Writing and Formatting Your Book

Here are some websites and tools worth investigating, whether you do embark on the NaNo journey or write your book some other way.

NaNoWriMo: If you’re interested in trying NaNo or in learning more, you should take a look at the website, https://nanowrimo.org/.

Scrivener: While you can certainly write your novel in Word or Libre Office or on Google Docs, some authors swear by one or another writing software program. The one I know and love is Scrivener. Its learning curve has intimidated some people, but you don’t have to bother with all its many bells and whistles to get great benefit from it. For example, Scrivener makes it easy to reorder scenes; to divide your working area into an outline on one side (or up above) and your actual text on the other side (or down below); or to look at one scene at a time. It’s not a lot more difficult to look at all the scenes from a particular POV, or all the scenes set in a particular location . . . et cetera. Here’s the link to buy it or to get it on a trial basis: https://www.literatureandlatte.com/scrivener/overview. (The trial period lasts as long as NaNo, thirty days, and the program is fully functional within that time. You can finish your novel and export the resulting text before it expires – if you haven’t gone ahead and bought it by then.)

Atticus: Industry standards for formatting paperback and hardcover books include:

- headers or footers containing page numbers and other information (e.g. author name and title)

- properly formatted chapter pages (the first page of a chapter): typically, no page number, starting lower on the page, and ideally with a drop cap and/or a word or two in all caps at the start of the first sentence

- front matter (title page, copyright page, possibly a dedication page) and back matter (Acknowledgments, Author’s Note, and/or information about future releases)

One can meet these requirements in Microsoft Word – if your Word software is robust and hasn’t developed any quirks (let alone poltergeists, like my version). It’s still a nuisance at best. Good formatting software can make this job easier. Many Mac users swear by Vellum, but Vellum isn’t available for PCs. A more recent arrival, Atticus, is cloud-based and can therefore be used with any operating system. There’s no subscription required, only a one-time fee (currently $147.00 US). Atticus can also produce files properly formatted for ebooks, though ebook formatting requirements are much less onerous. You can find out more or purchase it at https://www.atticus.io/.

Ebook and POD (Print On Demand) Publishing

Here are some ways to self-publish your book, if you’re so inclined. (Please note: many established authors, including some who were traditionally published for decades, now self-publish some or all of their books. Self-publishing is not the same as “vanity publishing.”)

Amazon (KDP): The easiest and cheapest way to publish a book these days is via Amazon’s publishing arm, Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP). For the Kindle ebook edition, you can upload a Microsoft Word file, an ePub file, or an Amazon-specific format called KPF. (You don’t need to bother about KPF unless you’re planning to use certain Amazon software to create your book.) There are ways to have fancier formatting for an ebook (Atticus, discussed above, can output such a file, though I don’t know the details), but I just upload a Word file with no page numbers and nothing in a header or footer, and occasional page breaks rather than specific section breaks. As for paperback and hardcover formatting, see my discussion of Atticus, above.

Amazon KDP has a beta program for hardcovers, which I haven’t tried, as it has a minimum length of 75 pages and I only want hardcover editions for my picture books.

Amazon doesn’t distribute to other retailers unless you check Expanded Distribution, which I haven’t used for almost ten years. I’m not sure how the royalty numbers currently compare to IngramSpark’s (see below), but the biggest problem I see is that KDP doesn’t allow you to make your books returnable (again, see below). If you do go the Expanded Distribution route, buy your own ISBN number for the book if possible rather than using a free one from KDP. Bookstores, even online ones, are likely to spurn any book with a KDP-generated ISBN.

You can get started on publishing a book through Amazon at https://kdp.amazon.com.

Draft2Digital: For years, Draft2Digital has been the easy way to publish an ebook “wide” (as opposed to exclusively on Amazon). Like KDP, it offers immediate previews of how your ebook will look – and unlike KDP, it has some built-in formatting options appropriate for different genres. The user interface is pretty straightforward, and you can download several ebook formats (.mobi, .epub, and PDF) to send to advance readers, whether or not you actually publish the ebook. Draft2Digital also has a paperback option, but I’ve never used it and can’t comment on or describe it.

IngramSpark: I’d guess that most self-published authors who want direct distribution to major online retailers (e.g. Barnes & Noble, BooksAMillion, Target) use IngramSpark to publish a paperback or hardcover edition.

Formatting requirements are in general the same as for KDP. That “in general” conceals some differences. IngramSpark’s processing software is significantly more finicky than KDP’s. It may, for example, refuse to process a file whose fonts aren’t all properly embedded, while KDP will flag the problem, fix it for you, and let you decide (based on how the book looks in the Previewer) whether it did a good enough job for your purposes.

IngramSpark will urge you to set a 55% discount for your paperback or hardcover and to make the book returnable, so that bookstores and other retailers will be more likely to carry it. If a retailer can’t return unsold copies, it’s highly unlikely to take the chance of stocking your book. As for the discount, last time I checked the retailer only gets about 40% of that discount, with the rest eaten up in IngramSpark costs of some kind. Setting your discount as high as 55% may make it hard to put a reasonable price on the book and still make any money (and I mean any). I’ve found that a lower discount, as low as 40%, doesn’t necessarily discourage retailers.

IngramSpark also publishes and distributes ebooks, but I haven’t used it for that purpose, as I’ve been satisfied with Draft2Digital for wide distribution.

Please note: Publishing through one of these companies is not the same as having them promote your book. IngramSpark has, or at least used to have, a book promotion program, for which you would pay and whose quality I haven’t tested.

As for the cost of self-publishing, much depends on which services you’ll need to hire someone to do, and which your skill set will allow you to do yourself (or to learn). There are also more expensive ways to print a book, especially if you want such extra touches as raised textures on your cover, gilt edges on your pages, or glossy full-color illustrations. If you can’t afford the services you need or the style of book you long to produce, you can undertake crowdfunding on a platform like Kickstarter. See Jon Auerbach’s article about Kickstarter on this blog.

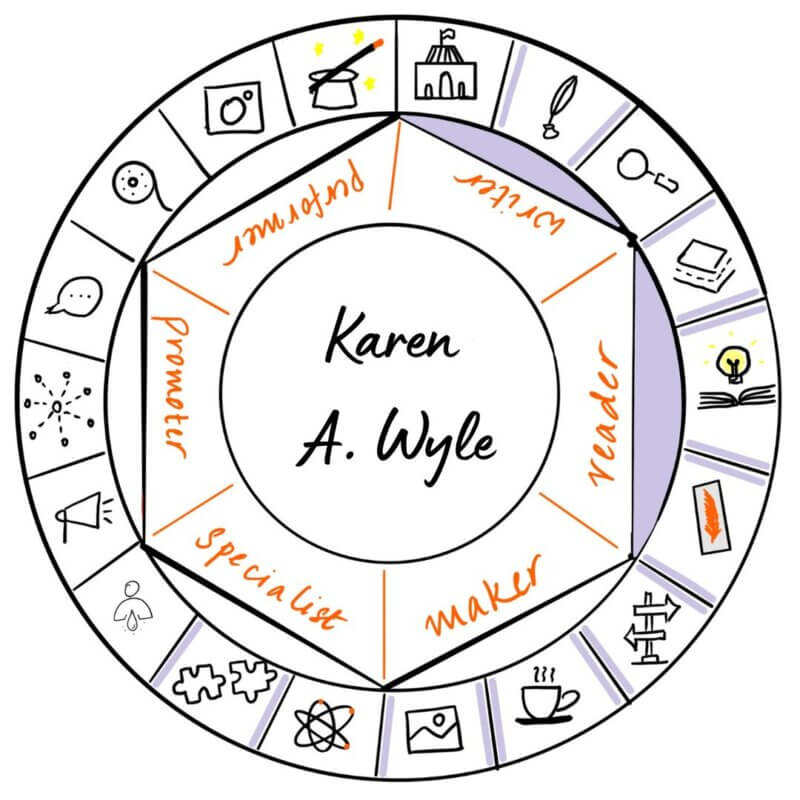

About the Author

Karen A. Wyle is the author of multiple science fiction novels, including her Twin-Bred series; YA novel Water to Water; and near-future novels Division, Playback Effect, Who, and Donation. Other novels include the afterlife fantasy/family drama Wander Home; the historical romance series Cowbird Creek, consisting of What Heals the Heart, What Frees the Heart, What Shows the Heart, and What Wakes the Heart; and the fantasy Far From Mortal Realms: A Novel of Humans and Fae. Wyle has also published one nonfiction work and collaborated with illustrators on four picture books.

Wyle’s voice is the product of almost five decades of reading both literary and genre fiction. It is no doubt also influenced, although she hopes not fatally tainted, by her years of law practice. Her personal history has led her to focus on often-intertwined themes of family, communication, the impossibility of controlling events, and the persistence of unfinished business.

Thank you for reading to the end of the post. I hope you enjoyed this guest post. Connect with Karen on Twitter, Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram and her website.

Be First to Comment