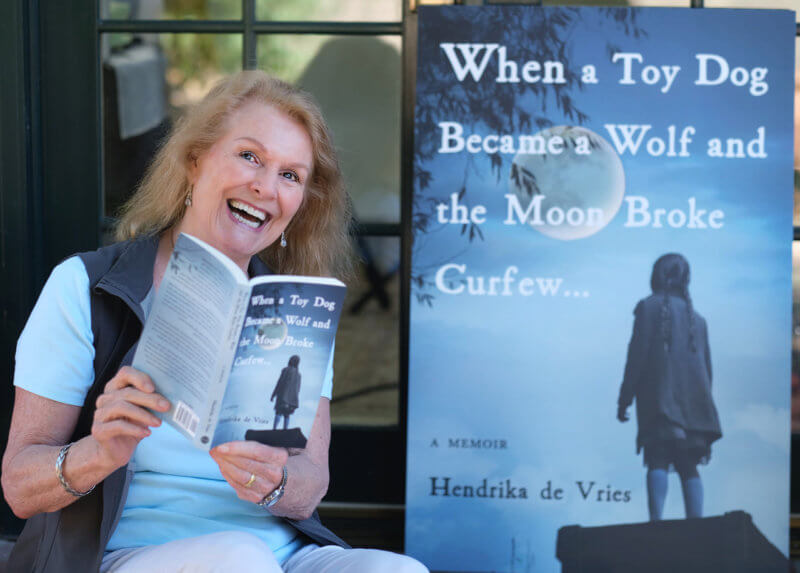

Yesterday I told you about Henny’s story in When a toy dog became a wolf and the moon broke curfew. Today, I want you to meet Hendrika de Vries, the author of the book. Hendrika de Vries was born and raised in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. She became a swimming champion, young wife, and mother in Adelaide, South Australia. When a toy dog became a wolf and the moon broke curfew is about her childhood in the Netherlands in the midst of the second World War.

I had so many questions for her about imagination, storytelling, her life in Australia and her parents! Take a look 🙂

- What led you to write your memoir and share your childhood memories?

As a family therapist and adjunct faculty at Pacifica Graduate Institute, I have taught and lectured on the topics of trauma, resilience and women’s empowerment for over thirty years. In that context I was able to share anecdotes of my childhood in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam with friends, students and colleagues. They urged me to write my memoir. I hesitated for many years, because it felt somewhat self-indulgent to write about my childhood trauma when I have lived a long successful life. So many others were brutally tortured and died horrible deaths under the Nazis. But when I saw torch-bearing neo-Nazis carrying swastikas in Charlottesville, Virginia, on my television screen and I witnessed the resurgence of white supremacist rhetoric, hatred, prejudice, and the current Administration’s attacks on women’s rights, I realized that I had no choice.

I believe that those of us who have witnessed how quickly freedoms we take for granted can be erased and how easily hatred is fanned into unthinkable mass cruelty, have an obligation to share our stories.

- Storytelling has always held an important part in your life, from the time your teacher, Miss Hoffman, held the class’ attention. What are some authors who your feel have perfected the art of storytelling?

Yes, I actually have been immersed in stories since I was an infant and my father told me bedtime stories. He was a lover of mythology and fairytales, so I grew up with the fantastic tales of gods and goddesses, of heroes and heroines, and of animals that could change their shape. Miss Hoffman, my first-grade teacher, captured my heart with her stories of goodness and kindness while evil stomped the streets outside the classroom. One of my earliest jobs was secretary to the Chief of Staff of the newsroom in a South Australian newspaper. The click-clack of the typewriters (yes, long ago, before we had computers) in the newsroom always thrilled me with the thought of all the stories that were being shared.

I have always been drawn to stories in which the characters reveal their passions and struggle with issues of moral conscience. As they are confronted by personal and cultural challenges that force them to grow beyond the comfortable limits of their current awareness, the reader is also challenged to do the same. I like to be drawn into a story where I get the sense that there is something of meaning to be discovered, something that even the protagonist in the story is not yet aware of.

One of my favorite recent novels is Anthony Doerr’s Pulitzer Prize winning All the Light We Cannot See. Doerr shows how young children are innocently drawn into the ideologies and cruel wars that we adults create. His story portrays Europe in the madness of WWII and draws the reader into the lives of a young German boy and blind French girl. We see their young and challenging lives being shaped on opposite sides of the conflict by the adults in charge. Yet ultimately, they are both part of a larger reality that reveals the interconnectedness of our humanity. Now, for me, that’s beautiful storytelling.

Isabel Allende has long been one of my favorite authors because she writes with both passion and cultural awareness. I enjoy her magical realism.

Toni Morrison’s Beloved, while painful and difficult to read for its graphic depiction of the cruelties of slavery, takes the reader into the moral depths of our shared humanity. Morrison, through the sheer power of her story-telling genius, challenges us to become aware and develop our own moral conscience.

I love to curl up with one of Kristin Hannah’s novels. Two of my favorites are her Winter Garden and The Nightingale. Hannah’s characters struggle with the ambiguities presented by war, love and survival. They face moral dilemmas that are rooted in true historical atrocities and situations, which force me, the reader, to let go of my own assumptions and judgments. I love that.

Jeanette Wells does that with her memoir The Glass Castle. She starts with seeing her mother digging through a dumpster. Immediately, we are confronted by our own inner prejudices that are challenged as the story develops.

- Did you have any expectations of Australia when you moved from your home country? How long did it take you to settle into this new reality?

I am currently working on a memoir that tells my story of being a Dutch immigrant girl coming of age in Australia in the nineteen-fifties. A “New Australian” as we were called in those days. The family dynamics were turned upside down, which is not unusual for first generation immigrants. My mother, who had been my rock in the Netherlands, did not speak English. My father and I both did. At home my father, my little sister and I began to speak English, while my mother and I would speak Dutch.

I was a teenage girl when we emigrated to Australia, so I had a sense of adventure but also sadness at leaving my friends. We lived in the Australian Bush for the first year, and I was homesick for my life in Amsterdam. I had been a competitive swimmer and attended a Lyceum in the Netherlands, but in the barren Australian Bush there was no swimming pool and no high school. I received my high school books and assignments by correspondence, and I began to dream of leaving home and traveling the world, which is probably how I eventually ended up in Santa Barbara, California.

- Did you get a chance to share with this work your parents? If not, what do you think their reaction would have been?

My mother always knew that I was in analysis and that I had told parts of our story to illustrate trauma and resilience in the graduate courses I taught. She supported me when I returned to Amsterdam to work on my memories with a Rabbi/Jungian Analyst. She never saw the finished manuscript, but I think she would have been pleased that the story is told through the eyes of the “brave” little girl. And, she definitely would have loved the “miracle moon” on the cover.

I shared the unpublished manuscript with surviving members of her family in the Netherlands. They knew her well and told me she would have like it.

My father was a very private man. He died many years before I started to speak about my memories in public, but he admired strong women and loved stories. He firmly believed in freedom of the press and a more just world for all. I like to think that he would have told me it was a well-written story. Given the resurgence of hatred and white supremacy in our world right now, he would definitely have understood my need to publish it.

- You have worked as a marriage and family therapist. What role do dreams and imagination play in life? How do you use them in your practice?

I believe that imagination plays a crucial role in our ability to heal. Imagination can reveal possibility and possibility gives us hope that in turn provides energy for action.

I think hatred and bigotry are rooted in a failure of imagination, a failure to see how connected everything is in the universe, and that kindness and caring for one another can create a better world for all.

As for dreams, I grew up with a mother and grandmother who talked about their dreams as everyday parts of normal life. Naturally, when I decided I wanted to become a therapist, I was drawn to the psychological theories of Freud and Carl Jung for whom dreams played a significant part in their treatment approaches. In my own practice, I helped clients explore their dream images as aspects of their personal mythologies, the patterns and stories by which they had shaped their lives. At times, the dream images revealed stuck places or repetitive patterns that had outlived their usefulness and were holding my client back from the potential or new paths they hid from themselves or were afraid to embrace. Dreams can reveal possibilities that need to be explored to free up creative energies for healing or new life paths.

I retired from private practice more than a year ago, but I still work with my own dreams, and at times friends and family members will check in with their dreams. It always feels like a privilege, an invitation to wander through enchanted forests and sacred gardens where hidden treasures await us. I guess in some sense my soul has never given up on the world of story that my dad introduced me to when I was a little girl.

- In your bio on She Writes Press, it says that your journeyed to Greece at one point in search for a mythical Goddess. What led you to do that? Tell me more about this journey.

In the mid-nineteen-seventies after my father passed away and my first marriage began to unravel, I experienced a spiritual crisis and went in search of meaning. I questioned our mainstream religious perception of God as an all-knowing male, and I became an activist for women’s equality. I went back to school to get my B.A. and saw how women with young children struggled to balance child-care, money and time in a heroic effort to further their own education. Their resourcefulness showed me, once again, what women can do when they put their minds to it. When they could not find or afford baby-sitters, they rented a trailer and set up a co-op where we exchanged baby-sitting services for the hours that we attended class.

After I obtained my B.A. I decided to attend Virginia Theological Seminary (an Episcopal Seminary) to study theology and support women’s rights to enter the all-male priesthood. In my studies I became increasingly aware of the lack of female images in our religious traditions that contemporary women could relate to. The women I had grown up with, my mother, my grandmother, were strong powerful women. I had watched my mother face Nazi-interrogation at gunpoint. My father respected strong women and had inspired me with a love of mythology, where goddesses matched capricious gods. I began to study mythology, read goddess literature and decided to join a study tour of the mythological sites in Greece and Turkey where powerful goddesses such as Athena, Artemis and Hera had been worshipped and revered for extended periods in our human history.

In my quest, I read books by depth-psychologists like Clarissa Pinkola Estés, who in Women Who Run With the Wolves explored the wild woman archetype and urged women to honor the wildness within themselves. I was also fortunate to be able to study with such renowned Jungian analysts and scholars as Christine Downing, Marion Woodman, Jean Shinoda Bolen, and others who taught that we need images of female power, strength and wisdom on which young girls and women can model their own lives.

I hope my memoir contributes to that mission in its own small way.

- History books are never able to convey the true experience of the people. Only stories like yours can depict those times correctly. Are there other memoir you would suggest to those who loved your book and the time it is set in?

Night by Elie Weisel. A dark and painful book, but a must read if one is to truly understand the Holocaust. Also, of course, The Diary of Anne Frank.

I would also recommend Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We cannot See, and Mary Fillmore’s An Address in Amsterdam. Although these are both novels and not memoirs, they accurately portray the impact of WWII events on the lives of innocent young people and children. Mary Fillmore’s An Address in Amsterdam is a novel that is situated in the area of Amsterdam where I lived as a child. Her research is so impeccable that I felt I was reading a memoir when I was reading her book.

To understand the plight of children and young people in WWII and any time or place where children suffer violence, hatred and oppression, I would also recommend The Children of Willesden Lane: Beyond the Kindertransport: A Memoir of Music, Love, and Survival, by Mona Golabek and Lee Cohen. And See You Tonight and Promise to Be a Good Boy! War memories by Salv Muller, a small Jewish boy who is hidden in a succession of homes in the Netherlands in WWII. Among the Reeds: The true story of how a family survived in the Holocaust, by Tammy Bottner (Amsterdam Publishers.com) is another one of the many good memoirs available.

I especially want to mention a recent memoir published by She Writes Press. It is Shedding Our Stars, by Laureen Nussbaum with Karen Kirtley. Laureen Nussbaum and I both lived in Amsterdam during the Nazi occupation. Laureen is Jewish and I am not. We also have a ten-year age difference and lived in different sections of Amsterdam. Despite those significant differences we share the emotional impact of having survived the cruelty and devastation of Nazi oppression. We also both experienced the hunger winter of 1944-45 in which thousands of people died of starvation. We did not know each other until She Writes Press announced the publication of both our memoirs. And, I think it is significant that independently of each other, in our books, we both stress the human goodness, resilience and resistance to evil that was also part of our experience.

(We will be co-presenting at the Elliott Bay bookstore in Seattle on October 27.)

- What is the hardest part of writing a memoir?

For me it was reliving the trauma with total honesty, so that I could convey it in a way that the reader would experience it emotionally and not just intellectually. For example, when I started on the chapters about the hunger winter, the months at the end of the war when my mother and I almost starved to death, I would sit at the computer and feel the overwhelming urge to call my mother on the phone. She had passed away many years prior and I had grieved the loss, but that did not erase this sudden need to hear her reassuring voice.

There is also a section in my book where my dad comes home after having been away in a POW labor camp for two years and I cannot access any feelings for him. When we had said good-bye, he was standing behind a barbed wire fence and I had asked a German guard to give him my tiny stuffed toy dog. In the bedtime stories my dad and I had shared, the toy dog often morphed into a wolf, a good wolf, and in my childhood imagination I firmly believed the toy could change into a wolf. I believed the wolf would protect my daddy and bring him home safely. But when he came home after two years of trauma and separation, I could not access any feelings for him. That is, until my father carefully handed me the flattened remains of the little toy dog that he had carried with him all that time.

When he gently reminded me that it was the “wolf” that I had given him, and that it had saved his life, my buried feelings burst through the emotional wall constructed during the years he had been away. I surrendered and fell sobbing into his arms.

Each time I tried to recreate that scene in my book, I ended up sobbing at my computer. I would have to get up and breathe, take a walk or make a cup of tea, before I could start writing again.

Another challenge was my deep desire to express the complete truth, and yet to acknowledge also that memory, especially childhood memory, is colored by family stories. We all remember our experiences through our own emotional makeup. It helped that my mother and I had often discussed our wartime experiences. I also took the unpublished manuscript to surviving relatives in the Netherlands to check it against their own wartime memories. They approved.

And finally, there is the question, of course, of everyone’s right to privacy and how we use names in our memoirs. It’s a question that has been discussed in many books on memoir writing. At first, I used only initials, but my editor thought that made my memoir read too much like a spy novel, and I had to agree with her.

I decided to slightly change the names of most people, but as I acknowledge in the Author’s Note of my book, some I could not change. To have done so would have felt inauthentic and dishonorable to their memory.

** When a toy dog became a wolf and the moon broke curfew is now out in stores so get a copy and let me know what you think! Let’s have a book-discussion! **

Amazon Print

Amazon Kindle

Cover image: Photo by Greg Rakozy on Unsplash

What a wonderful interview, Kriti. Both … Wolf … and Hendrika’s work in progress sound like great reads. She name checks many books I love, including All The Light We Cannot See. Another novel I’d recommend to you both is The Wish Child by NZ author Catherine Chidgey. Set in Germany during the war and told from the point of view of two German children from families who supported the war, the novel has a sting in the tale that is truly shocking and powerful.

That sounds like an amazing read, Angela! I’ll add that to my reading list with all the books Hendrika suggested.