My teaching philosophy is to cultivate the love for lifelong learning in my students by helping them find a connection between the curriculum and their interests. I want them to interact with each other and explore avenues they might have been curious about, but have not pursued yet. As I read Trevor Mackenzie’s book, Dive into Inquiry, it affirmed my belief that I can realize my teaching philosophy through the medium of inquiry-based learning.

I believe in a Constructionist approach to teaching, giving students multiple opportunities to build and improve concrete artifacts that represent their learning and inquiry-based learning offers the perfect blend of exploring a passion and creating a memorable token of the process.

At the heart of inquiry-based learning are the Four Pillars of Inquiry: the reason to pursue inquiry. Apart from elaborating on the Four Pillars, I will also explain the components of inquiry, when students are in-charge of their own learning. Lastly, we will look at the four models of inquiry and I will analyze how principles of inquiry apply while designing our lesson plans through Understanding by Design.

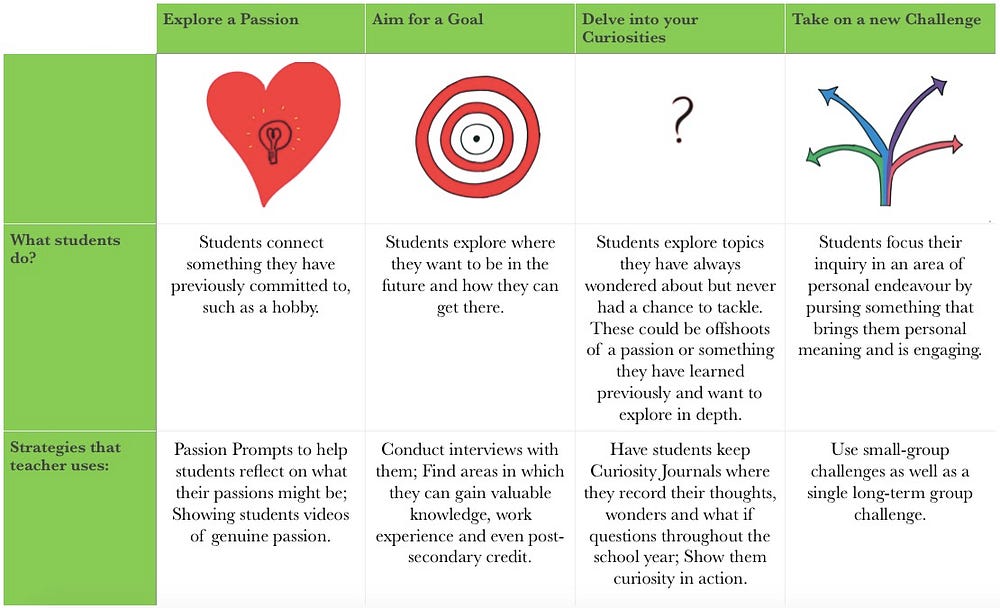

The Four Pillars of Inquiry

Think back to a time when you wanted to learn about something, outside of required studies. Why were you so curious about this topic? What did you hope to gain after becoming more knowledgeable about this topic? Wasn’t that an exciting time? Did you feel a sense of accomplishment and exhilaration afterwards?

Maybe you were pursuing a passion, finding the answer to a question or problem that you were curious about, maybe you wanted to reach a goal you had set for yourself or you wanted to challenge yourself. It is likely that the reason for your inquiry falls into one of these broad categories.

For each of these categories, Trevor offers certain ways in which students pursue them as well as giving teachers the strategies that they could use, depending on the reason for inquiry that the student is engaged in.

Think back to the time you engaged in inquiry: why do you think you stuck to the process of finding answers? What motivated you to keep researching? When students pursue projects in one of the four pillars, they are more inclined to stick with their inquiry. They are intrinsically motivated to learn and quench their curiosity. They have found a personal connection to their projects and, as a result, the task is more meaningful.

Relationships are an integral part of teaching. By letting students engage in inquiry and individual projects, we are able to get to know the students better as well as meet their needs. Here we have an opportunity to effectively use differentiated instruction and scaffolding for the concepts that they might struggle with during their inquiry!

The Four Pillars of Inquiry are the starting point: they model how inquiry can begin. Where do we look when we want to learn something? Who do we ask? We ask ourselves. And we let our students ask themselves too.

Pursuing Inquiry: The Five Components

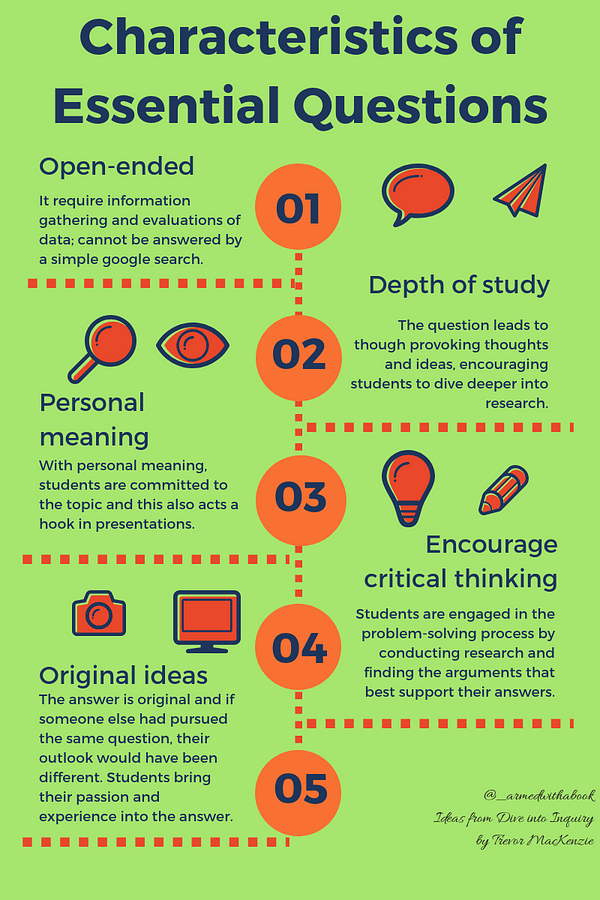

Component # 1 Creating essential questions

We learn to find answers to a specific question. Without the specific question, our learning would not be well-directed.

For example, I have been tasked with creating a brochure for Culturally Responsive Teaching. If I google the term, whether on the web or on scholar, I find thousands of results. I could look through many of these results and eventually come up with what I want to say about the topic. Or I could save myself sometime by making my search directed:

What is CRT? How can I implement it in my classroom? What advice does the teaching community have about it?

My searches would be more meaningful and at the same time, I would browse less information. Are all the questions I pose in my search essential questions?

How can I arrive at an essential question (and help my students create their own essential questions)? Trevor mention three steps:

- Conduct preliminary brainstorming and research. This is to get the lay of the lands. What are people talking/writing about in this particular topic of interest? Why is this important?

- Refer to libraries and online databases to get more direction. I find the abstract of research papers and excerpt from articles are often helpful in finding the essence of information and choosing which resources to spend more time on.

- Transform the topic into an essential question! Draft a couple of questions, review them with someone. See what your students come up with when they are engaged in inquiry processes of their own.

Based on the characteristics of essential questions and the three step process, for my assignment, I came up with: How can I become a Culturally Responsive teacher? This is open-ended and has personal meaning to me because I always think of application of what I discover.

We need essential questions to guide us to uncover the bigger picture, dig deeper and sometimes convince ourselves about creating new habits.

Component # 2 Proposing and planning

Every project and assignment needs some form of planning to be completed successfully. At any point in time, we are all working on many projects, some more important than others. Planning allows us to keep the project in perspective. By having our students discuss the plan and their proposed approach with us, we can guide them better, ask thoughtful questions about time constraints that they might not have considered or were quite optimistic about. We can find out where we can be of help to them.

In one of my curriculum classes, we were discussing a potential project that a student might take as a credit-course in Shop class. The project was to refurbish a used car and potentially sell it. The role of the teacher would be to work with the student to find the car that they could afford to buy and then review the timeline of refurbishing it. This would further involve setting some time to inspect the car, find the tools they would need, the changes they want to make to the car and so on. If the student is doing this in the course of the term, some serious planning is required!

Component # 3 Exploring, researching and collecting evidence

Inquiry is not about answering the essential questions based on our intuition and prior knowledge alone. It involves researching, exploring and documenting all that we are learning. This documentation is called learning evidence.

Learning evidence is important because it helps in information retrieval as well as in processing information. When I read books about education, I highlight sections and then reflect on what they mean to me or where I have seen the strategy in practice. This helps me process the new ideas I am seeing as well as refer back to them later, without picking up the book itself.

Taking the time to explore is key. Research can take us in many directions and it helps to be open to ideas we had not anticipated we would find. Reflecting on these ideas is learning in itself.

Component # 4 Creating an Authentic piece

An authentic piece is an artifact that students will keep forever. It inspires and resonates long after it has been completed. It isn’t the notes that were made from many sources — it is the way the student summarizes all the learning. The final authentic piece that is created, and eventually submitted to the teacher or showcased in a display, is the finished product that the student was working towards.

In the inquiry model where students choose the kind of authentic piece they want to create, it can be anything, from a website to a podcast to a sketchnote — any way that they believe they have best expressed their answer to the essential question. In this model, the criteria for authentic pieces should be co-construct by student and teacher. Other times, this piece would be determined by the teacher. For my assignment, the brochure is the authentic piece that I must create.

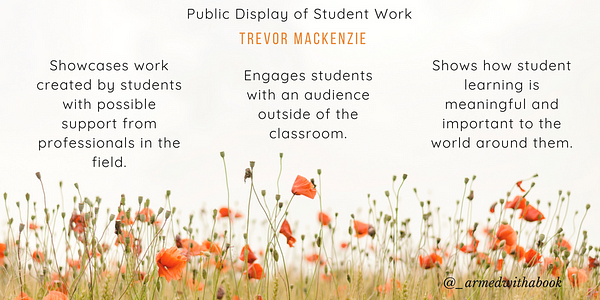

Component # 5 Public Display of Understanding

When you walk in the halls of your school, do you notice any of the student work on display? Do you ever stop and keenly observe one of these works and wonder about the student who made it? Some of the classrooms where my classes happen have some student work displayed there. I do not know who made it but it always makes me curious. That is what I love about this component of inquiry.

The displays make me think of the students who were there. Similarly, if I saw such displays in the school where I teach, I would get a glimpse into the students who I might end up teaching as well the growth of students who were with me in previous years. As Trevor aptly puts it, the public displays are reminders that students have burning questions too and the will to pursue them.

When we give our students the chance to find answers to their questions, we give ourselves the opportunity to get to know them better and see them grow in front of our eyes, learning from the curriculum while attaining their own goals.

The Models of Inquiry

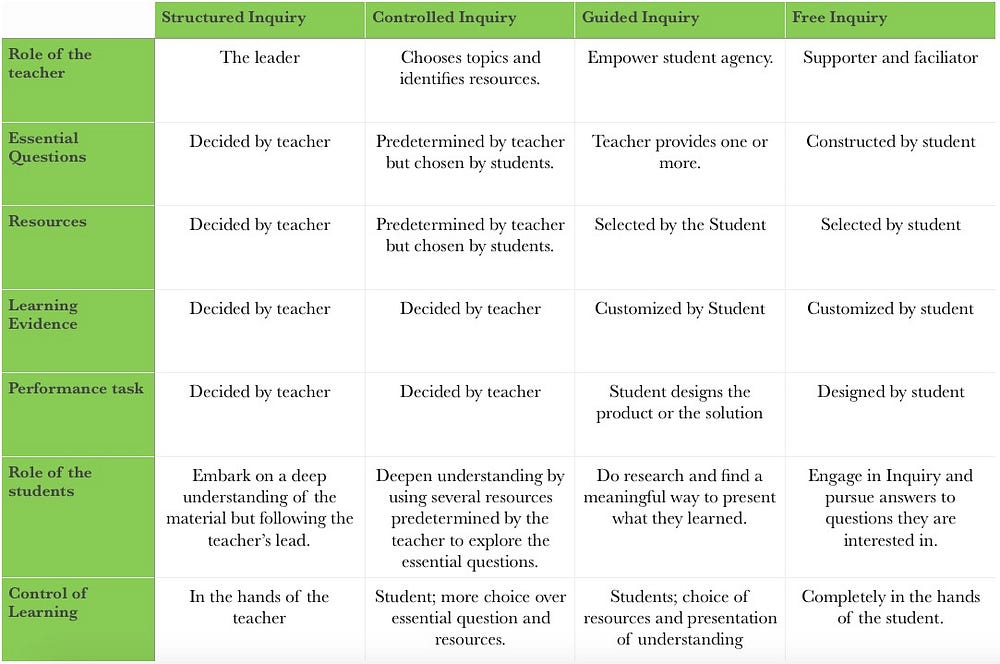

There are four inquiry models that are explained in Dive into Inquiry. The Four Pillars of Inquiry and the components of the inquiry process are present in all four models. The difference is the amount of influence that teachers and students have in each area.

For a teacher new to inquiry, it makes sense to start by just dipping a toe in water. Creating a structured inquiry lesson involves choosing the essential questions, resources, type of learning evidence students must collect, and the performance task (authentic piece in assignments)— these are all decided by the teacher. How is this different from usual teaching you might ask… It is inquiry-based because the students explore the resources to find answers, rather than being given the answer right away. They come to their own responses to the essential questions based on the resources and their knowledge.

Letting students have a little more say can be achieved through the controlled inquiry process where the teacher still presents the essential questions and resources, however, the students gets to choose which questions they want to answer and suing which resources. Think about Universal Design for Learning for a minute and Multiple Intelligence theory. For resources, you might provide some videos, websites to explore, a digital simulation, maybe or a short book to read. Based on their interests and the kinds of materials they like to engage with, students will choose their resources to find answers to their essential questions. I would probably choose the book and websites. 🙂

In guided inquiry, teachers give more choice to the students. Along with the essential questions and the resources, students can choose how they want to present their learning. They could create a short video or a presentation or a brochure… any way they feel they can express their discovery best!

In the three models above, it was on the teacher to create essential questions, find resources, and express how students should showcase their learning. In the free inquiry model, the students collect and design everything. The teacher is now the facilitator; the students are masters of their own learning process and outcome. It is usually this free inquiry stage for which there will be public display of student work. I like to think of this stage where we have, as teachers, taught them how to develop their own inquiry units and pursue them.

Once they have tasted inquiry and built their artifacts representing their learning, would students not want to be lifelong learners, asking their own questions, pursuing their curiosities and passions?

How can you use inquiry during lesson planning?

A fantastic resource that Trevor mentions in his book is Understanding By Design by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe. Since learning about inquiry-based learning and its implementation in the classroom and the . When we develop our lesson plans by thinking of the essential questions and evidence of learning, we are taking an inquiry approach to planning.

The Understanding by design (UbD) process, Wiggins and McTighe explain, has three stages:

- Starting with the goal in mind: Think about the essential question that is at the heart of your lesson or topic. What is the big idea you want students to explore further or be curious about?

- Determining how to assess the students — how will you decide they have achieved: This relates to learning evidence and artifacts that they will create.

- Planning the experience: What are the resources that they would need? How can you support your students to help them achieve a certain level of understanding?

Even if I was not planning an inquiry-based unit, asking these questions for my lesson plans would help me get a clearer picture of where I want to take my students.

In its simplest disctionary definition, inquiry is

a systematic investigation — Merriam Webster Dictionary

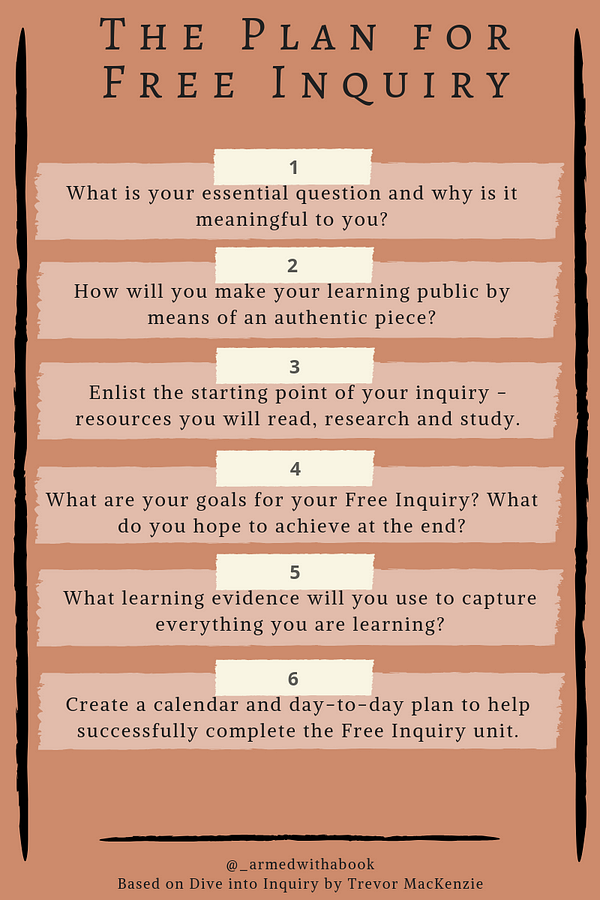

When we follow a similar approach to planning, whether it is a lesson or a unit or the whole year, we equip ourselves with resources and prepare ourselves for situations that we might encounter in the classroom. Here is the visual I had made for Free Inquiry. Think about how it applies to your lesson planning. Think of learning evidence as some form of assessment and day-to-day plan as a check-in with the students, reviewing or revisiting concepts to continue building their understanding… any remnants of lesson planning there?

In Dive into Inquiry, Trevor encourages teachers to teach students about UbD and have them implement the process throughout their learning.

Isn’t it beautiful when we teach planning strategies to students that we use too? 🙂

I have only scratched the surface of the knowledge that Dive into Inquiry uncovered for me. I hope that you will find the time to read it and you too will gain confidence and enthusiasm about inquiry-based learning in your classroom and routine practices!

References:

MacKenzie, T. (2016). Dive into inquiry: Amplify learning and empower student voice. EdTechTeam Press.

Wiggins, G. P., Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Ascd.

Further Recommendations:

National Research Council (2000). Inquiry and the National Science Education Standards: A Guide for Teaching and Learning. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/9596.

Be First to Comment