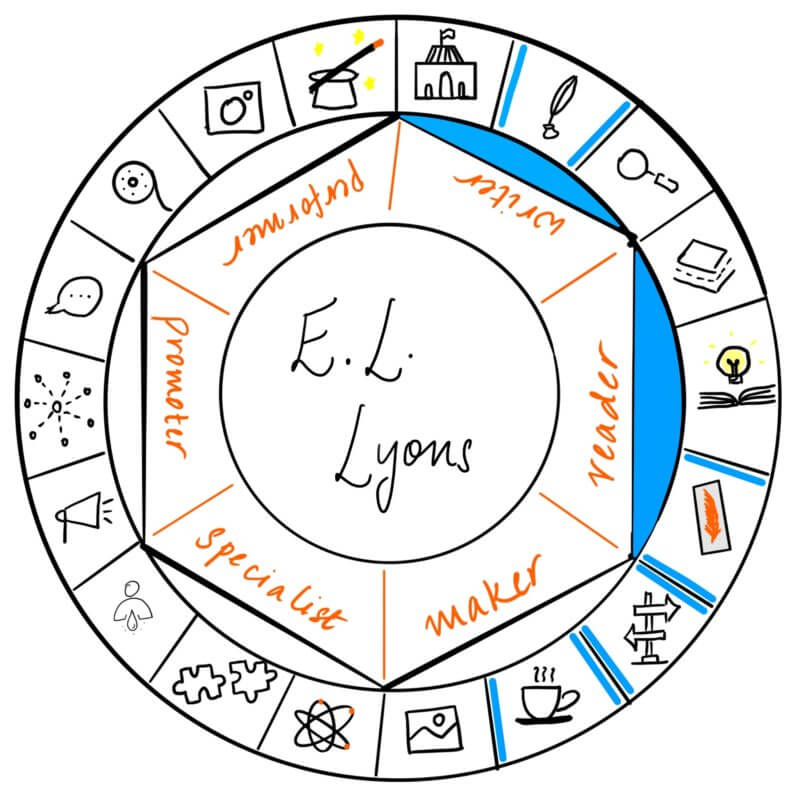

Welcome friend! A few weeks back, I had the pleasure to host E.L. Lyons, author of Starlight Jewel and hear her thoughts about flexible plotting. Today, she is giving us a glimpse into her experiences with beta reading, as a reader and receiver of feedback. When El sent me this post, I found things I want to do with my own writing on the blog. Even if you aren’t a beta reader or author, being is a writer and interesting in writing is all you need to enjoy this post. Let’s get started. 🙂

Beta Reading

Guest post by E. L. Lyons

I was unaware of what beta reading was when I first began exchanging beta reads with other authors. I’m not a very social person, and I wasn’t active on social media save for posting the occasional cat photo and keeping a collection of memes on Pinterest. I found a “review exchange” website, thenextbigwriter.com, and started exchanging chapter reviews with others. It was an overwhelming and confusing experience at first. Over the last couple years though, I’ve gotten a heaping ton of experience in beta reading for others and having my work beta read.

Why should writers also beta read?

Firstly, even if you don’t join such a site (there’re others too, like critiquecircle.com, I’ll post a resource list below), I recommend that every author spends some time beta reading. Don’t just beta read one piece of work. Beta read some things that you think are great, beta read some you don’t like, beta read some that need a lot of work. Each of those experiences will teach you something new.

Why help? You have your own books to write, a stressful full-time job, medical issues, family issues, five cats to feed (okay that’s just me), and a TBR stack of published books calling you from the shelf. Beta reading takes time and mental energy, surely, someone less busy should be doing that.

Except that there are actually some very good reasons to help. One of those reasons is that everyone else is busy too, you’re not special, neither am I. But let me also appeal to how it’ll serve you as a writer.

Learning to breakdown and analyze writing

I sometimes refer to my writing mentor (who has done an absurd amount of beta reading) as a book mechanic. He’s able to read a chapter and dissect it, each sentence, each paragraph, each underlying motive, each character’s voice etc. then make little repairs on each thing until suddenly you have a real functioning chapter. He doesn’t ever tell me what to write, only tells me what he believes is not working and why (I’ve yet to master this). Once I know why something’s not working, fixing it is a whole lot easier.

When I first started beta reading for others, my insight was… useless. I knew two things: when I liked something, and when I didn’t like something. Aside from spotting typos and mix-ups, I was not a good beta reader. I wasn’t even a good confidence booster considering that I disliked just about everything I read. I just didn’t know why.

Slowly but surely, I learned how to pick things out, spot the real issue, the cause of my dislike for most of what I read. Just today I was reading an already-published book and compulsively making notes about the plot hiccups and overdone dialogue and repetition. Now I can not-enjoy-books much more productively than I used to not-enjoy-books, as it seems to be a particularly beloved pastime of mine despite my supposed love of books.

What I’ve learned to ask myself when beta reading:

What is the writer trying to do?

What are their strengths?

What parts of their writing are doing what they’re meant to do?

What parts of their writing aren’t doing what they’re meant to do?

What parts of their writing aren’t doing enough?

What parts of their writing aren’t contributing at all?

What parts of their writing are too much?

Kriti’s side note: I personally love these questions! As a reviewer, though I don’t give feedback to the author, I do think about how the story is written. These questions are very helpful in reflecting on the writing and understanding my experience with the book.

Oftentimes, it’s not about whether I like something or not, especially if I’m beta reading a YA Fantasy or a thriller, which I’m guaranteed to dislike. Nor is it about whether the author is a “good writer.” Every writer can get better, the worst and the best both have room to improve. The best writer, when trying to do something new and different, can still utterly fail.

However if you can see what the author is trying to do, and where they’re falling short, then you can help.

Applying those skills to your own writing

So how does this help? Now I can not-enjoy-my-own-book productively. Every time I read my writing prior to learning this skill, I knew I didn’t like it, but I couldn’t figure out what I didn’t like. Now, I not only know what I don’t like about my writing, I almost always know how to fix it. When I don’t know how to fix it, at least the problem is tumbling around in my head waiting for me to develop those skills. Often, I find the skills while beta reading for someone else.

Learning new skills

Which brings me to why it’s important to ask what people are doing correctly in their writing. Yes it’s good for them if you point it out and tell them, give them those warm fuzzy feelings of praise, but it also helps you to notice it, break it down, and put it into words. “Hey that dream scene came out really well—I felt truly disoriented, I think it’s because you did X, Y, and Z—I might try to replicate those techniques in my book.”

The more you objectively and critically analyze the work of others, the more you’ll be able to correct and apply what you’ve learned in your own writing.

You can’t do this with a diet of traditionally published books that have been edited. There are of course exceptions, and if you are like me there’s a lot to dislike in just about any book. But you’ll often find that even if you don’t like a book—it’s still doing what it’s meant to be doing, it’s just not doing what you would like it to do. I can’t stand a book with a sheltered FMC, but that’s a viable trope that lives on because many people do in fact like it and more importantly, that’s often what the author is trying to do.

Being a part of their journey

Moving on, beta reading is also just incredibly rewarding (mostly, we’ll talk about when it’s not here in a bit). Watching a writer change their misshapen attempt at a story into a respectable book is almost as exciting as doing the same for your own book.

One of my two most cherished beta read projects is now moving into the query phase, and I can honestly say I’m thrilled. I’ve been helping with this book for over a year, and seeing this author’s breakneck-speed improvements over that time has been a wonderful experience. No one works harder than this author and I see that day after day in our morning and evening writing sprints, weekly Ladies of Letters meetings, the chapter revisions that flood my inbox, and the amazing development of her own beta reading feedback on my own book.

Finally, this is the surest way in my experience to create a really solid bond in the writing community with people who are in your genre, know a lot of what you’re going through, and can help you and advise you along the way.

Be picky

Before I move on, I would also like to give a word of advice to anyone who intends to beta read for others. Be picky. Don’t agree to anything and everything. Think of the worst traditionally published book you’ve ever read—it had already been beta read, picked up by an agent, picked up by a publisher, edited, and proofread. Beta reading is the first step on that ladder, and these books have had none of that meticulous attention. There are certainly exceptions, especially if the author has several published books under their belt, but typically, you’re going to be reading a very rough book. It isn’t the best of the genre. It isn’t polished. And you’re the first guinea pig. They’ll change the formula (hopefully) before giving it to the next guinea pig.

Because of this, you want to stick to your favorite genre(s), ask for an excerpt or first chapter, and ask questions about the content before committing. Some questions I ask because the answers matter to me: Is there spice? Is it YA, NA, or Adult? Is there sexual assault? What tropes does it have? What type of magic and what types of fantasy creatures are in the book? The answers to those questions often determine whether I’ll pass on a book. Figure out what answers are important to you.

Treat your beta readers right

A few paragraphs back I said that beta reading is incredibly rewarding. That was a half-truth. While I have had some beta bonds bring me joy, others… have left me seething. Still others simply leave me confused or disturbed. So before I go into how to attract beta readers or how to get the most out of them, I’m going to go over some general etiquette and generally how to treat your beta readers like the generous and deserving members of your team that they are.

Beta readers are never wrong

No, you don’t need to take every suggestion your beta readers make. In fact, it’s impossible because they’ll all have conflicting opinions on things (unless you have your MC kill a horse… I have confirmed that they will all agree your MC should not kill horses). That being said, your beta readers are never wrong. They’re giving you honest (hopefully) opinions, and those opinions are valid.

Even if you think their opinions are stupid or offensive or totally miss the point of your point—they are still not wrong. Opinions can’t be wrong, and you should be thankful for their honesty, time, and contribution even if you disagree or are hurt by what they said.

I have seen authors shame beta readers on social media. That’s a crappy thing to do to someone who volunteered their time to help you. Don’t be that author.

Also don’t be the author who argues with their beta readers (debating is okay, clarifying is okay, but don’t be defensive) or gets fresh with their beta readers. They are not wrong. That doesn’t always mean that they’re correct, but it does mean you should respect their opinion, thank them, and move on. If they hated your book and detailed why, that’s a more valuable and useful opinion than if they’d given you false praise. If all you want is praise, don’t bother with beta readers and never read your reviews.

Lamenting

Giving critical feedback and being honest isn’t easy. I would love to tell my writer friends that I love all their books. I don’t. A lot of times my feedback is small things, but sometimes… I have to drop a hefty critique that I know is going to hit hard. I spent days deliberating and trying to figure out how to word a critique recently because I knew if the writer took it, she’d be rewriting the ending of her book, including several chapters. I felt the guilt because I know how much work it is. She took the criticism to heart, did a big rewrite, and the new ending is so much smoother.

However, oftentimes when I give a big critique, or sometimes even just a lot of little nits, writers will start in with lamentations about how bad they are at writing. It is never my intention to discourage someone from writing, and the whole point of this process is to help people get better at writing. When these lamentations start, I have to become a comforter. I am not a good comforter. I’m more like an itchy quilt. I usually slip away from the project shortly after such an event because I no longer feel I can be honest with that person.

If a critique hurts your feelings or your confidence, don’t lament your lack of skill or your feelings of failure to your beta readers. Learn from the critique and become that much better. There is no reason, none at all, for you to make your beta readers shoulder the guilt of discouraging you. Their criticism is there to help you become better, not to tell you how bad you are.

Apply the feedback

If you tell me that you’ve had five beta readers already and I’m hit with an eight-paragraph wall of exposition and a dozen typos in the first chapter… then I know exactly what’s going on. You’re writing not applying any feedback between beta readers and I’m noping out of your book.

Why is this not okay? For one, you’re asking me to do the work someone else has already done—and neither of us are getting paid to do this work for you. You should be updating your MS each time you get feedback and trying to make the experience more enjoyable for the next beta reader. There’s also only one way to tell if your changes were effective—testing them on another reader.

I beta read a few chapters for one writer who was going on and on in a forum about how her beta readers always ghosted and she couldn’t keep them. I was curious as to what could be so bad about her story to have so many people disappear. As it turns out, it wasn’t her story that was the problem, it was her. I gave pages of written feedback in addition to in-line comments on her first few chapters. She never replied. Not even with a “thank you” or “you suck.”

Someone else fell into her trap. They reported that she hadn’t even fixed the typos. She had taken zero percent of my feedback, never replied, and then sent it to another beta reader in the exact same form six months later.

She mentioned in the forum we’re in that she “forgot about my feedback” at one point when I was talking about beta reading in the forum (I hadn’t mentioned her, but maybe she felt called out).

I realized that she didn’t actually want beta reader feedback. I still see her in the forums talking gleefully about how she’s finished writing another book (none published, none edited), then lamenting her lack of beta readers. What she wanted was for someone to read the book and tell her it was amazing. If this is what you want, please, for the love of books, send your manuscript to your mother.

If what you really want is feedback to help you polish your book, apply BR feedback regularly and have the manners to say a simple thank you.

Honesty

An honest beta reader who’s willing to tell you when something is bad is worth their weight in gold. If a beta reader is only pointing out grammar things and loves every aspect of everything you write otherwise… they’re probably not being honest. Beta reading isn’t about grammar and spelling—sure, BRs can and should point those things out, but they’re real purpose is to tell you what parts of your story are working and what parts aren’t. If the plot is weak, if the characters are unlikable, if the dialogue is overdone, if the villain isn’t enough—beta readers are there to tell you.

Value an honest beta reader, appreciate them, and encourage them to stick around. You don’t need someone who’s just going to tell you they love every character, every scene, and every plot point. That’s a beta reader who isn’t doing you any favors.

Getting the most out of beta readers

Chapter-by-Chapter

Going chapter by chapter with your beta readers has a lot of benefits. One is that you can edit ahead based on people’s feedback. Some changes you make aren’t just going to affect the one spot, some change a thread or item or place throughout the whole book. Sometimes someone noticed you overuse sighs or misspell a word consistently. If you’re only sending one chapter at a time, you can make those changes, then send the new chapters out, making each subsequent chapter more enjoyable for your beta readers.

In addition, since your readers will be going at different speeds, you can edit a chapter before sending it to someone new.

Finally, this makes it a lot less overwhelming for you beta readers because they’re working with bite sized pieces of your book so it seems like less work. Even if they do ghost or quit out eventually, you’ll still get feedback up to that point. In addition, you aren’t overwhelmed with a book’s worth of feedback each time someone finishes.

Picking the right BRs

Not every beta reader is right for every book, and you have limited time. It can get overwhelming to sift through the feedback of a dozen people, and you don’t really need that many. You’ll find that some people give you feedback that really transforms your story into what it’s meant to be, and some people suggest changes, but nothing really essential.

But you might also have two BRs who are essentially always pointing out the same things. You don’t need two people to do one job. Try to find a handful of reviewers who each have a skill that makes a significant difference in your book. Sometimes finding the right people is just a lot of trial and error with the wrong people.

Reading other indie books can give you an idea of people’s strengths and other indies are sometimes willing to do beta read exchanges. So keep an eye out while you’re reading for people who are skilled in the areas where you need work.

Betas vs alphas vs groups/sites/classes

Beta readers are the readers who read your already finished, already edited to the best of your ability draft. Alpha readers are those who read your book as you’re writing it. This distinction isn’t quite as important after you’ve finished another book and published it, but it is kind of important before then. Why? Because a lot of people start writing books and don’t finish them or run out of steam or get a new idea and abandon the first story—in which case you’ve wasted people’s time.

Until you know that you’re willing and able to take a book to completion, there’s no need to use alpha readers. Finish your draft and do edits yourself on your first book before asking around for beta reader feedback.

However, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t get feedback while you’re writing. I actually wish I hadn’t spent so many years afraid to show people my writing because it was so bad. I could have been improving so much more quickly in that time if I had just had the courage to try.

So, where is the appropriate place to get feedback when you’re practicing or drafting? Sites like the one I started on, thenextbigwriter.com, are a great way to get some initial feedback. They work on a point system and there’s no real commitment, so you give a little feedback and get a little. This can evolve into a more solid beta reading relationship, but it doesn’t always.

Writing groups and/or classes are also great places to get feedback, especially if it’s just for one scene or chapter or a short story. They can also provide prompts and offer some writing accountability.

Where to find them?

Some Paid Sites:

- www.Thenextbigwriter.com and/or www.booksie.com (they’re basically the same site, run by the same guy, just difference writers on each)

- www.Critiquecircle.com

- www.Critiquematch.com

- www.Betareader.io (free and paid version)

Some Free Sites:

- https://www.reddit.com/r/BetaReaders/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/destructivereaders/

- https://www.scribophile.com/beta-readers

Other Plotting Resources:

If you have any questions for El, pop them in the comments below. We love hearing from you!

Thank you for hanging out with us today. Connect with El on Twitter, Instagram and her website. Check out her indie book recommendations here and the post on flexible plotting here.

Cover image: Photo on Unsplash

For several years, I beta-read speculative short stories and chapters from fantasy novels once a week via a free SFF site, Critters. Though not every story was gripping, I always read to the end and wrote between 400-1,200 words of feedback.

One WIP was especially memorable: the first draft of “Lost Dog at the Drive-in.”

Plot: two friends at a drive-in, searching for a dark and quiet spot to urinate, discover that a strange woodlands dweller has been preying on a lost mutt. Since one female works at a vet clinic, she takes the starving pooch home to nurse it back to health, unaware that she will now be the monster’s new target.

A year later, the author confessed that the overwhelming feedback she received on “Lost Dog at the Drive-in” compelled her to take her own story more seriously – – and thoroughly revise it.

After this incident, I started my own speculative critique group. 🙂