Universal Design for Learning, or UDL, comes from architectural studies and is aimed at designing products that are usable by everyone. In the 1980s, architect, Ron Mace, wanted to build physical environments that as many people as possible could use. The inspiration for UDL comes from him. Common place examples of universal design in architecture are sidewalks and ramps. It is important to remember that universal design is not a one-fit-all technique: each of the designs benefit most people but not everyone. For example, sidewalks may cause people who are blind to not know where the road ended.

In today’s classrooms, we have a diverse set of learners and no matter how much a teacher wants to address the needs of all learners, it takes time to know the students and understand them better to give them the supports they need. This is where UDL comes in handy: in terms of education, UDL is seen as curriculum-based approach, meaning it is applied before the teacher knows her students. The aim is to have lesson plans and materials that are accessible to as many learners as possible.

By promoting planning for diversity in terms of text available to the students, activities they would perform as well as the teaching methodology in use, UDL allows the teacher to be reflective and adapt the curriculum to as many student needs as possible. With the advent of technology, this is made easier. Consider the flexibility offered by ebooks to increase font, change contrast between the text and background, and in some cases even the font of the text. In my article on Boumas I explored how certain fonts help in ease of readability. That was an example of UDL as well as we can print material in different fronts or allow students to change the font of the text to improve their ease of reading.

The Centre for Applied Special Technologies (CAST) has extensively worked on UDL and defines it as:

The term Universal Design for Learning means a scientifically valid framework for guiding educational practice that:

-

provides flexibility in the ways information is presented, in the ways students respond or demonstrate knowledge and skills, and in the ways students are engaged; and

-

reduces barriers in instruction, provides appropriate accommodations, supports, and challenges, and maintains high achievement expectations for all students, including students with disabilities and students who are limited English proficient. (CAST, 2011, p. 6)

UDL is based on neurological research and aims to make students expert learners. The three guiding principles of UDL together work to make students resourceful, knowledgeable, goal-directed, strategic and purposeful, motivated learners – all characteristics that expert learners have. Thus, the principles serve as a blueprint that allow teachers to create lesson plans and activities that meet the needs of all learners from the very beginning. Instead of designing for the ‘average’ student, they allow the teacher to think about the diversity in the classroom and ensure that the materials used and the goals presented are customizable to reach as many learners as possible. It is easy to mistake the word ‘universal’ to encompass everyone. In the UDL context, a universal curriculum is one that can be used and understood by anyone.

The Brain Systems

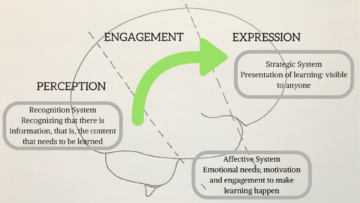

Neurological research has found that there are three systems in the brain that work closely. These are the recognition system, the strategic system and the affective system. The recognition system is present in the back of the brain and is responsible for identifying patterns. It identifies the ‘what’ of learning – what has to be learned. At this moment, it would be this article that you are reading. The frontal lobe and the anterior of the brain act as the strategic system, allowing us to understand the information in ways that make sense to us. As you read this article, you would be able to identify which points resonate with you most, filtering out what you need to know and remember. This is the ‘how’ of learning – the schema and connections we make to information presented to us and how we present it ourselves. The affective system, situated in the middle of the brain, is responsible for engagement and motivation. Why we care about learning something comes from here.

The three principles that form the UDL framework are centred around each of these brain systems. The goal is to provide students with different ways to perceive (recognition system), relate to (affective system) and process (strategic system) the content.

- Principle 1: Multiple means of representation – This means providing multiple ways in which learners can engage with the material. As Maths teachers, we are encouraged to present Maths concepts in three ways: concrete, in the form of physical objects students can touch an manipulate, pictorial, which is presenting information by drawings and graphs, and using symbols, in equations and variables. In this way, there are not only many opportunities to receive information, but also opportunities to use different tools, auditory methods, for example, to present information.

- Principle 2: Multiple means of action and expression – This relates to giving options to learners in how they can express their understanding. It could be in the form of physical actions, use of technology, mind-maps, anything that makes sense to them as the best form of showcasing what they understand.

- Principle 3: Multiple means of engagement – There need to be many ways of looking at the content and relating it to learners’ personal interest. This keeps them motivated and self-regulated to learn more, as they are able to learn through something they are passionate about.

The way I find it easy to think of this information is as follows: Without perceiving information, we can’t really hope to understand it. If I haven’t seen or heard about something before, there is a very low chance I know about it. The back of the brain is responsible for picking up the information we perceive. Once something has been perceived, work begins for the affective part of the brain which drives the learner to understand the content and continue being motivated to understand it and express their knowledge. No one can really see how you understand something till you express it in a presentable manner. The front strategic of the brain relates to this expression and shows what the learner has gained out of the experience.

Pardon my very crude drawing of the brain.

Implementing UDL in Practice

Let’s take a look at how to implement UDL in education. The fun part is that this is not just limited to lesson plans. A teacher must consider the physical (classroom set up), social (interaction between teachers and learners) as well as the academic environment (related to the syllabus or curriculum) of the classroom to implement UDL successfully and for the learners to be able to gain the most out of it. The acronym ACCESS is quite helpful in this regards. After deciding on a teaching tool or strategy, a teacher can analyze it in terms of ACCESS:

A: applicability to each learner, considering those in the margins as well

C: capability to be flexible

C: clarity and ease of understanding for learners, hence, thinking like the student

E: expression and communication of information to learners: do they know what to do?

S: safety considerations – are mistakes welcomed?

S: size and space – for example, manageability of the class, movability for furniture.

CAST provides many resources online to help teachers think in terms of UDL. The online tool is a great way to check which aspects of what each principle addresses and how it can be incorporated. A one-page checklist is also available from Colorado State University.

Conclusion

I have only scratched the surface of UDL here. Though it is aimed at all learners, it shares some similarities with differentiated instruction which is catered to individual learners. I also did not elaborate on the constituents of the UDL curriculum and how we can analyze the given curriculum to make UDL more practical. I hope to pick them up in a future article soon.

Peter Sims (2011) , a columnist in New York Times writes in his article Daring to stumble on the road to discover :

Invention and discovery emanate from the ability to try seemingly wild possibilities; to feel comfortable being wrong before being right; to live in the world as a careful observer, open to different experiences; to play with ideas without prematurely judging oneself or others; to persist through difficulties; and to have a willingness to be misunderstood, sometimes for long periods, despite the conventional wisdom.

Thus, the process of invention and discovery involves being able to take chances, accept mistakes, learn from others and being open to experiences that might scare us. When we create an environment where everyone is welcome and we are not teaching to the ‘average’ student, and instead accepting and welcoming diversity in how we think, model and implement lessons and activities, we will be able to inculcate the love for learning in our students.

References

CAST (2011). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.0. Wakefield, MA: Author.

Class notes from EDPY 301 Adaptive Education, Winter 2018, University of Alberta. using the following book:

Hutchinson, N. L. (2013). Inclusion of exceptional learners in Canadian schools: A practical handbook for teachers. Pearson Education Canada.

Sims, P. (2011). Daring to stumble on the road to discover. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/07/jobs/07pre.html

Further Readings

Hall, T. E., Meyer, A., & Rose, D. H. (Eds.). (2012). Universal design for learning in the classroom: Practical applications. Guilford Press.

Meyer, A., Rose, D.H., & Gordon, D. (2014) Universal design for learning: Theory and practice, Wakefield MA: CAST. Available through CAST.org

Comments are closed.