Lauren gave me the idea to do book timelines – when did I first hear about the book? When did I get around to reading it and sharing about it? Here is what my investigation revealed: I first heard of We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies by Tsering Yangzom Lama in March 2022. I got a copy from the publisher through NetGalley in the same month and now, it is over a year later that I am finally telling you about it. Let’s not delay further.

We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies

By Tsering Yangzom Lama | Goodreads

In the wake of China’s invasion of Tibet throughout the 1950s, Lhamo and her younger sister, Tenkyi, arrive at a refugee camp in Nepal. They survived the dangerous journey across the Himalayas, but their parents did not. As Lhamo-haunted by the loss of her homeland and her mother, a village oracle-tries to rebuild a life amid a shattered community, hope arrives in the form of a young man named Samphel and his uncle, who brings with him the ancient statue of the Nameless Saint-a relic known to vanish and reappear in times of need.

Decades later, the sisters are separated, and Tenkyi is living with Lhamo’s daughter, Dolma, in Toronto. While Tenkyi works as a cleaner and struggles with traumatic memories, Dolma vies for a place as a scholar of Tibetan Studies. But when Dolma comes across the Nameless Saint in a collector’s vault, she must decide what she is willing to do for her community, even if it means risking her dreams.

Breathtaking in its scope and powerful in its intimacy, We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies is a gorgeously written meditation on colonization, displacement, and the lengths we’ll go to remain connected to our families and ancestral lands. Told through the lives of four people over fifty years, this novel provides a nuanced, moving portrait of the little-known world of Tibetan exiles.

Content notes include death of a loved one, colonisation, invasion, infidelity, displacement, loss of culture.

We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies – Review

I grew up so close to Tibet and yet I knew almost nothing about it. Having been to Dharamshala, the city that is home to the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibet, and Tibet’s government-in-exile, I was too young to ask myself then what led to this exile. I am glad that now that I am older and see books that can fill in the gaps in my understanding from the past, I pick them up.

The Story in Broad Strokes

Lhamo is not even ten when her family has to leave their village. She becomes the main caretaker of her younger sister, Tenkyi. I loved seeing them grow up and how protective Lhamo is of Tenkyi. Their mother is an oracle and in the very beginning, it becomes clear how the Chinese view the Tibet people and their spiritual beliefs. Amma is charged with leading the people to safety and over the course of the journey out of Tibet and into Nepal, their group becomes smaller. They lose people to sickness and the days of hunger and uncertainty weigh heavy on all the travellers. Eventually, they are given a place to settle down for the time being. They all had hopes that they would be able to return back home.

For the first half of the book, when Lhamo is young, there is still hope to go back. The people in the community talk about it. Everyone left their homes at different times during the invasion. People try to find their surviving family members in other camps. There is a lot of sadness in this book. The Tibetens have a custom of burying what’s important to them in their home so that it is still there for them when they come back. The people hope that countries like the UK and USA would speak up for them and stop the atrocities done to them.

Nothing happens. Time passes and fifty years go by without going back to the village where the people came from.

The Characters

There were four main perspectives in We Measure the Earth with our bodies

- Lhamo, how she takes responsibility of her sister and the life she builds with her uncle and community in exile in Nepal,

- Tenkyi who is the child everyone has high hopes for. She is one of the few people to leave Nepal and study abroad. The hopes of the family are on Tenkyi and how she will make things better for everyone. Their dreams are now about freedom and living, with not so much hope of going back home.

- Dolma is Lhamo’s daughter and has the opportunity to study abroad in Canada. There she discovers the statue of an old saint that she knows to be of reverence amongst her people. It is one that appears in times of need. I loved this mystical aspect of the book. To believe in something bigger in ourselves and find solace in it. To accept the timing in things.

- The saint becomes the reason for the fourth perspective – that of Sempel, the man Lhamo fell in love with, the father that Dolma does not know.

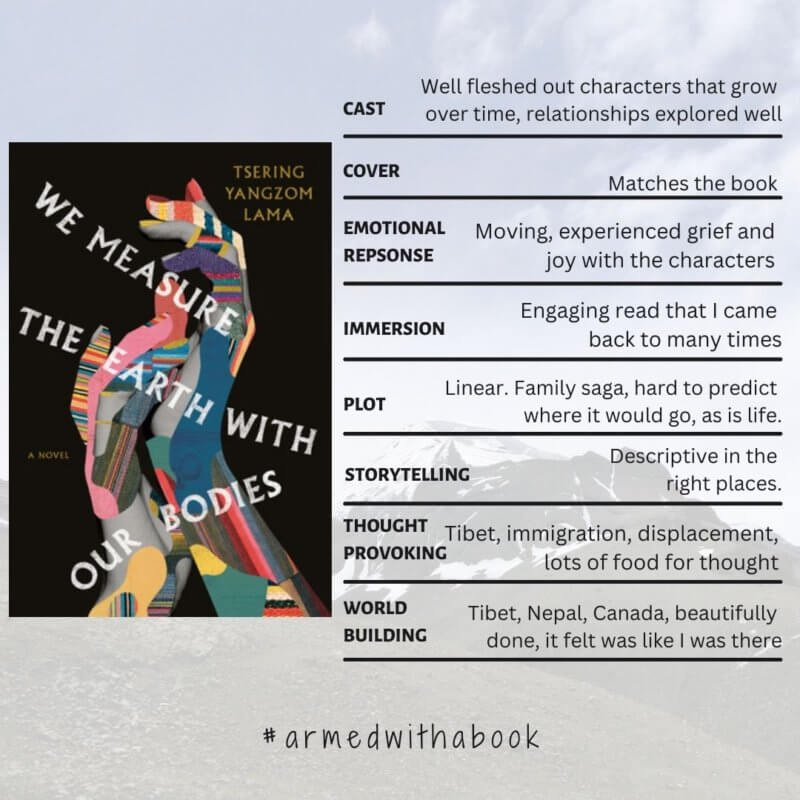

We Measure the Earth in our Bodies immersed me in its culture, religion and love. In so many ways I felt understood. With the characters, I felt the pain of losing loved ones, the hardships of adjusting to a new country, the pressure of doing well and the peace of making the best of the circumstances. In the rituals for death and prayer, I found my own culture reflected. In Tenkyi I saw my aunt who recently passed away and I am overjoyed in some ways that I can see her in books.

Displacement

This book made me reflect on the loss of culture due to displacement. Things that are commonplace when we are home that we no longer talk about when we are far away. I have experienced this in myself.

I used to think that the way for a culture and language to survive is with its people. This book and to be honest, what I think all indigenous books portray is the importance of land. How without the place that we come from, we are incomplete. Our culture cannot survive the same way in a place that has been given to us when our rightful place has been taken away from us. This is a painful truth that fills me with grief. I am fortunate to have roots in the land I was born in but I am far away now and no longer speak my own language with my own people. I already question what I will be able to pass on to my kids.

Sometimes it is not in our hands though. Some things are too painful to talk about while others make no sense if they cannot be experienced in the true setting. Lhamo and Tenkyi grieved for their mother and her knowledge. Amma did not have enough time to teach them. Leaving their homeland and finding safety somewhere else was the goal. Later, though Lhamo has settled in a camp when Dolma is born and brought up, she too is unable to pass on her history and knowledge to Dolma. Some of it is because of grief – losing her mother so young changed her. And maybe some of it because the land is key to knowledge.

I learned about the smuggling of Tibet artifacts out of Tibet to become part of private and museum collections in the West. I loved that the characters felt a connection to their heritage artifacts and wanted to claim them back for themselves. The bureaucracy to bring back what is rightfully theirs was ridiculous and sadly expected. This line will always haunt me:

“What I do know is that survival is an ugly game, and our objects are all the world really values of our people. Our objects and our ideas. But not us, and not our lives. Whether we’re here for another two hundred years or wiped off the face of the planet, it doesn’t matter to anyone else, not really.”

Samphel in We Measure the Earth in Our Bodies

Thank you for reading my thoughts. There are deeply personal things that I add to my reviews. Reading is not just about the story, it is also an opportunity to reflect on my past and future, beliefs and prejudices. I loved We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies even though it was a hard read. I would go back to it. The audiobook had a full cast which I did not get the time to try out – maybe next time. 🙂

Have you read this book or do you plan to? Add it to your Goodreads shelf.

This wrap ups all the reviews for Scotiabank Giller Prize 2022 finalists! It has been a lot of fun reading them and bringing them all to you. Stay turned for the wrap up post early next month!

Be First to Comment